The lack of required documentation among the undocumented population seems to be the biggest barrier to applying to New York’s Excluded Workers Fund, a relief fund designed to include these workers.

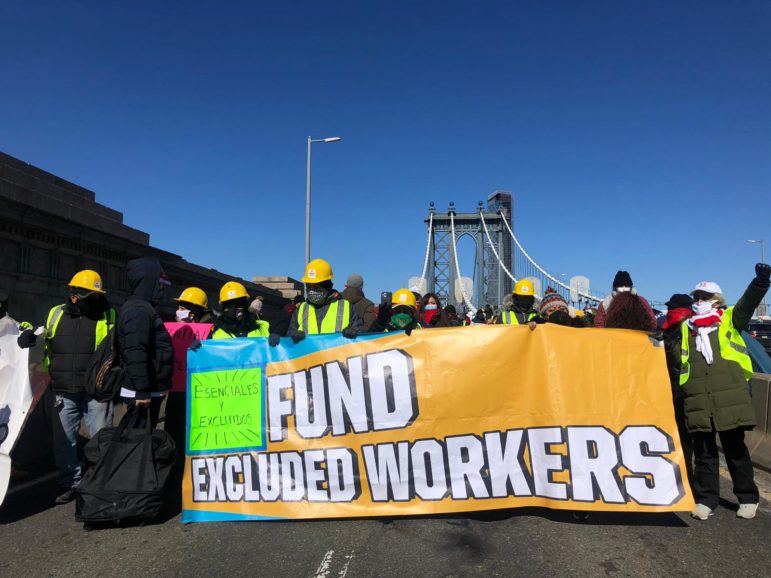

Courtesy Make the Road New York

Immigrant workers and advocates marched across the Manhattan Bridge ON March 5, 2021, calling for the state budget to include funding for those who have been excluded from pandemic relief.This article originally appeared in Spanish. Lea la versión en español aquí.

Yovani Bravo knew that the favor he was going to ask his employer earlier this month hinged on finding his boss in a good mood. At that point, the only requirement Bravo had yet to complete in order to apply to New York’s Excluded Workers Fund was to have the employer write a letter to prove his Tier 1 eligibility, with which he could receive up to $15,600 (minus $780 for taxes) in COVID-19 assistance.

“I have a good relationship with him, but he told me he didn’t want to fill in the letter,” Bravo says by phone. “Employers don’t want to get involved.”

Bravo has worked painting and renovating houses in upstate New York for seven years. “Ever since I came to New York I’ve worked for him,” he said.

After the first denial, Bravo kept insisting, with the help of a letter and some notes he had been given at the Workers Center of Central New York, one of 60 organizations selected to assist New Yorkers applying for the fund. Bravo explained the best he could with his limited English proficiency that the excluded workers fund was a program for workers like himself who did not receive unemployment insurance during the pandemic.

“I told him it was really a benefit for me. And he knows I have family here and in Guatemala,” Bravo said.

In the conversation, Bravo navigated his employer’s fears and lack of knowledge about the fund, such as whether employers will be reported for providing employment certification letters (they won’t) or whether they will later have to pay the costs of the assistance workers received (again, they won’t). So Bravo put the Workers Center of Central New York on the phone with his employer.

After the conversation with the organization, his employer finally agreed. “My case was a bit complicated, but I can’t imagine when there is a bad employer-employee relationship or when they know each other for a short time,” imagines Bravo.

The excluded

Bravo completed his application on Aug. 18 and had no technical problems with the application platform. However, he does not stop thinking about a colleague he works with, who apparently will not be able to apply to the fund because he does not have the necessary documents.

Abelino, who asked not to use his last name, has no documents to prove his identity. Unlike Bravo, he does not have a driver’s license, or passport, or any of the documents accepted by the state as part of the application process. “Appointments for the passport are very long-term,” says Abelino by phone explaining why he has not renewed his passport.

It’s precisely this lack of documents that leaves out many workers who the state fund was designed to aid. These workers and advocates went on a 23-day hunger strike this spring to have the aid included in the state’s budget. Days before the program launched, they also demonstrated in front of the Department of Labor (DOL) offices in lower Manhattan and Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s office demanding more flexibility in the documentation requirements.

But those requirements did not change when the fund opened on Aug. 1, and now organizations selected to assist New Yorkers with applying say that many people who should qualify cannot apply due to lack of documents. Advocates believe this should be corrected, otherwise, the workers will be doubly excluded—from earlier pandemic relief aid and unemployment benefits, and now from the state fund that was supposed to fill that gap.

Other groups have found applying difficult too, like “workers who have worked under a different name,” explains Jessica Maxwell, executive director of the Workers Center of Central New York. Some workers do this for fear of being detected by the government, she explains, and at other times to be able to work in certain industries. Abelino is one of them, and he doesn’t think his former employer will agree to give him a letter.

Maxwell says there is a power relationship behind a requirement like an employer letter. “The applicability to the fund depends on a third person, and workers have to go through this uncomfortable situation with their employers,” she said.

“Employers have all the power to decide who applies to this fund,” Maxwell adds. For many workers, this employment letter can make the difference between receiving up to $15,600 (minus taxes) in Tier 1 of the program or $3,200 (minus taxes) in Tier 2, or simply nothing.

To be eligible for Tier 1, applicants need to score at least five points, or three points for Tier 2. However, obtaining the necessary score is not so simple: Documents such as an ITIN, W-2, wage statements, or an employer letter immediately give five points, but for Tier 2, at least one of the documents with a value of three points is needed; applicants cannot combine three documents with a value of one point to qualify.

This issue has caused several organizations to focus on workers who have the necessary documentation to apply immediately, while they wait to see whether or not the DOL, the state agency in charge of administering the fund, makes updates to the application requirements. Some have already been made.

“For a few days, there was no option for undocumented people who—for some reason—had a Social Security Number, so the DOL recently changed that,” Maxwell says, hoping the letter requirement will also be modified.

While there is the option of submitting a letter from a charity registered with the New York State Attorney General to confirm the applicant’s work history, this is worth only one point under the system.

Bianca Guerrero, the Fund Excluded Workers campaign coordinator at Make the Road New York, believes one way to fix this would be to offer applicants the ability to submit an employment letter they write themselves attesting to their work history, or expand the options to include other types of documentation.

“Domestic workers are going through the same thing,” says Guerrero by phone, explaining that the lack of the employer letter has been a constant problem for the most informal workers, who are not on a payroll, are not paid by direct deposit and do not have pay stubs.

Other obstacles

The second major obstacle in the application is proof of residency, as many workers are not named on a lease or only rent a room that they pay for in cash, or in the case of farmworkers, have employers who provide their housing.

Abelino, for example, worked in an upstate New York dairy when the pandemic began, meaning other proofs of residence accepted by DOL—such as utility bills like electricity, gas, internet, cable, and water—are also in the name of third parties. “Even the phone bill was in the employer’s name,” detailed Abelino.

Carola Otero Bracco, executive director of Neighbors Link, a nonprofit organization serving Westchester’s immigrant community, says proving residency has been difficult for seasonal workers. “It’s unfair that this system is causing these workers to lose these funds,” Otero Bracco said by phone.

Since the program opened, the organization has assisted a couple of hundred workers applying, “mostly for Tier 1,” specifies Otero Bracco, reiterating that there is a large group of workers waiting to see if they can apply if the DOL refines the other documentation requirements.

Other organizations in the Westchester area such as Community Resource Center, dedicated to training and integrating new immigrants in the county, have also seen quite a few problems with documentation.

As of August 11, they had five would-be applicants cancel their application appointments because they didn’t have the needed documents to apply, according to Executive Director Jirandy Martínez. “Our 10 successful applications have submitted for Tier 1. No tier 2 just yet,” she said.

Technical and practical problems

The DOL responded to City Limits that the application platform for the excluded workers fund has not had any technical problems. However, organizations who’ve been helping people apply report several.

For example, workers who have applied using a language other than English have received notifications in English, and in some cases, workers have missed the opportunity to make changes to their applications because they did not understand the message sent to them.

“By the time she came to ask us, the response window had already expired and could not be modified,” explained Carina Kaufman-Gutierrez, deputy director of the Street Vendor Project.

This specific problem was anticipated by the organizations months ago. During the design stage of the fund, it was recommended to the DOL to ensure that all written notices were in the primary language indicated by the applicant.

When organizations do not know how to solve an applicant’s problem, they do not have a hotline or a direct point of communication within the DOL, so they have had to create communication channels among themselves to solve problems together or exchange suggestions.

In cases in which applicants have a problem filling out the application, they can call the state’s hotline (877-662-4886 for Spanish) and book an appointment to talk to someone over the phone for help. But advocates say those appointments are not always honored and applicants are left waiting for the call, unable to solve their issues.

During the design stage of the fund, advocates recommended that the DOL provide in-person and one-on-one video conferencing options for application assistance throughout the state, but this measure has also not been adopted. Recently the DOL did implement a chat bot to provide virtual assistance.

Some applicants looking to apply as soon as possible who were unable to log back into their initial application form have mistakenly opened a second one, which may jeopardize their application status, something organizations are already warning their members about. On Sunday, Aug. 23, the DOL announced that it “has found various duplicate claim situations where applicants unknowingly created new accounts when attempting to simply resume their original application or respond to a request for additional information.”

Some organizations also report having problems uploading heavy PDF documents to the platform and in other cases, the system requests the same or more documents that were not listed as required. For example, if the driver’s license was used as proof of residency, then the applicant receives a message indicating that the license is needed as proof of identity, even though it had already been uploaded.

Advocates have also asked the DOL to submit progress reports on how the fund is being administered, to get a clear picture of how the money is being distributed (funds are supposed to be doled out on a first-come, first-served basis) and make sure some areas of the state aren’t left behind.

The executive directors of Healthy Community Alliance and Huntington Family Centers, which operate in the Western and Central areas of the state respectively, say they only began outreach in their communities a few days ago.

Advocates also asked DOL to report on how many applicants got approved, what tiers, and how many were denied, but the department has not provided this information. City Limits has communicated for several weeks with the department and did not get this information either.

“It is too premature to release metrics on the program as it just launched August 1,” the DOL replied several times by email. Community organizations estimate 10,000 people have applied so far.

Hours after applying to the fund, Bravo said he was excited and hopes the amount he receives will be more than enough to pay off the more than $8,000 he has accumulated in debt to stay afloat during the pandemic.

“I turned to my friends to borrow money,” Bravo said. “There are expenses that don’t stop: car payments, insurance, gas, food for the baby, clothes. Plus I have a family to support in Guatemala.”

On Friday, August 20, the Department of Labor reported on its Facebook account that the first group of applicants have been approved to receive payments.

6 thoughts on “NY’s Excluded Workers Fund Excludes Many It Was Supposed to Help, Advocates Say”

I will like to know if you file your taxes jointly can that person file for the excluded workers funds separately

File the taxes with ITIN number jointly I will like to know if you can file for the excluded workers funds separately i

Hola mi nombre es Ariana y por error duplique mi aplicación y ahora fue denegada, quiero saber si podría presentar otra solicitud

I missed the application deadline. Is anything like this going to happen again?

I changed my number an I forgot to update my application so now u can’t get the 8 digit code what can I do to fix the problem to activate my card plz help me I need the help plz

Did your card come in the 7-12 business days? I’m waiting for mine currently. & on the bottom of the EWF click contact us and ask to speak to a representative they will give a call back time and you can change it that way. Here’s the number 877-393-4697