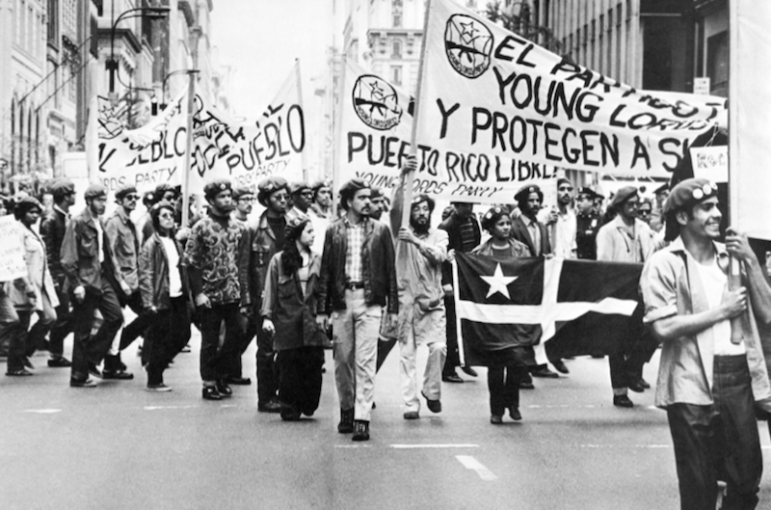

They wore jeans, T-shirts. Some wore military jackets. Others wore colorful dashikis, combat boots, sported big Afros, and wore purple, black, and brown berets as they walked down Lexington Avenue in New York holding signs saying “Serve the people” and shouting “The people united will never be defeated.”

The year was 1971. Some of the marchers were from the Black Panther Party or belonged to allied organizations like the Puerto Rican Student Union. In the lead of the march was a group known as the Young Lords.

Like many young people now, the people marching on October 20, 1971, were dissatisfied, angry, demanding change. There was no Black Lives Matter movement, but like their 2020 counterparts they were protesting and demanding respect for Black lives. They were fighting against police brutality, racism and U.S. imperialism and shouting, “Wake up Boricua, and defend what is yours.”

“It’s basically all this stuff you see now, but on steroids. There was the civil rights movement, the war in Vietnam, Puerto Ricans had just been recognized as part of the country, but they looked at us like we were aliens. Nothing was bilingual,” says Carlito Rovira, who joined the Young Lords at age 14.

The Young Lords were born as a gang defending the Puerto Rican neighborhoods in Chicago in 1959. Over the years, as groups like the Nonviolent Student Coordinating Committee (SNCC) emerged and Chicanos began developing the concept of “brown pride,” Jose “Cha-Cha” Jimenez, a one-time gang member who had been in and out of jail, adopted the name and the Young Lords evolved to become a political organization to fight against police brutality and violence, racism and oppression in what the Young Lords called “AmeriKKKa.”

Now, young people are marching again. Some ex-members of the Lords think there are lessons from their experience for today’s young activists and parallels between the protests of the 1960s and today’s new era of challenge.

The origins of the Young Lords

Adi Talwar

Carlito Rovira, a member of the Young Lords, in front of the First Spanish United Methodist Church, also known as the People’s Church located at the intersection of Lexington Ave and East 111th St in East Harlem.What began as a gang in the area of Oldtown near the north side of Chicago in 1959 then became a Puerto Rican nationalist party that expanded to New York City with offices in the Bronx, East Harlem, and the Lower East Side.

What enabled the transformation from a turf gang to a political movement, as founder Cha-Cha Jimenez told in an interview included in Darrel Enck-Wanzer’s book The Young Lords: A Reader was to start asking the community they protected, what did they need? “So they got together to find out what was the real problem, how could they help their people best. This was the main reason why the Young Lords Organization turned politically.”

So Jimenez opted to keep the Young Lords name because it was already recognized by the community. The New York Young Lords, with a different yet related history to the original Chicago Young Lords, emerged in December 1969 when, inspired by the Black Panther Party, they wanted to directly address issues of food insecurity, poverty, and the lack of access to education and health care.

“Fred Hampton [who became leader of the Black Panther Party in Illinois] formed the Rainbow Coalition that included the Students for a Democratic Society, the Blackstone Rangers, and the Young Lords. So the Black Panther Party served as a role model. We had similar urban experiences,” says Martha Arguello, a former member who is now a professor at Claremont College.

The Young Lords’ first political project in New York began when they went to the First Spanish United Methodist Church in East Harlem, on the corner of 111th Street and Lexington Avenue.

“We couldn’t even get in the front door. We wrote letters, began attending services, and talked with the congregation, but the church’s Board voted no,” says the book about the Young Lords edited by Darrel Enck-Wanzer.

On December 28, the Young Lords took over the church and renamed it the People’s Church. “For the next 11 days, we ran free clothing drives, breakfast programs, a liberation school, political education classes, a day-care center, free health programs, and nightly entertainment (movies, bands, or poetry).” Then, as Enck-Wanzer explains, the Young Lords wrote a set of core principles, their ideological pillars—a 13-point program and platform.

The organization was colorful and diverse. “There were some Vietnam vets, ex-gang members, lesbians, recovering alcoholics, ex-convicts, Dominicans, Filipinos, Cubans, other Latinx, and 20 percent of the organization, at that time, was African American,” says Iris Morales, who was with the organization from 1969 to 1975.

The Young Lords had a great impact and achieved important health care reforms. They trained themselves on how to perform tuberculosis testing and started a testing program in their community. Along with the Black Panther Party, the Young Lords used lead poisoning as a symbol of racial and class oppression, until in 1971, Congress passed the Lead Paint Poisoning Prevention Act.

“We never talked about how many we were. The organization took off when the New York branch opened. Within a year it expanded to the East Coast (Hartford, Philadelphia) and branches were opened where there were Puerto Ricans. There were 14 branches in the United States,” Arguello says.

By 1974 the Young Lords had lost order and cohesion and all the original Young Lords had resigned. In addition, the FBI’s counterintelligence program known as COINTELPRO, created to dismantle movements of the 1960s, had several of the leaders surveillance.

The Past and the Present

According to Ed Morales, a lecturer at Columbia University’s Center for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, “the Young Lords can teach Latino communities that it is necessary for progressive movements to recognize that our community is subject to several levels of discrimination based on race, gender, sexual preference, and social class, and that they all must be dealt with together.”

“The Young Lords also show that a strong critique of the economic system is necessary and that direct political action is necessary beyond representation as elected officials,” Ed Morales says.

There is also a necessity—that many Latino activists have already embraced— of finding common cause with Blacks and other marginalized groups. “The knee that killed George Floyd represents slavery. It represents the oppression that suffocates” Rovira says. He believes there is a deep history to the alliance between Blacks and Latinos in what is now the United States. “In the [U.S.] Southwest, African Americans fought against whites. In the war against Mexico, African Americans fought for Mexicans.”

Rovira also sees the Black quest for human rights as a model “The struggle against the oppression of Blacks provided a standard, a united effort to be liberated. Black people are the architects of that principle. Without the Black Panther Party, one could not speak of the Young Lords,” Rovira says. “Even that 20 percent of African Americans [who were part of the Young Lords] understood that they were inside a Puerto Rican struggle, and they knew that fighting would benefit them.”

When comparing the Young Lords’ past with the current situation, Iris Morales sees both progress and setbacks. For example, now “there are more Latinos politicians, there are more Latino journalists,” but on the other hand “in several areas we are worse off: the level of incarceration, the lack of protection for unions, White supremacy. Now climate injustices are more complex, as well as surveillance, and we are in the middle of a pandemic.”

“The day before the pandemic began was not a great day either, so what ‘normality’ do we want to return to?” asks Iris Morales. “We are in a time that offers great suffering but also great opportunities. As Audre Lorde said, ‘there is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.’”

The Young Lords created alliances with women, LGBTQ organizations, local, state, national and international struggles.

According to Ed Morales, the Young Lords “broke the mold of passive acceptance of social injustice by Puerto Rican and other Latino groups and set an example for activism that would continue for decades.”

In addition, as a Latina feminist, Iris Morales points out that “police brutality, discrimination, and unemployment affects us [women].As feminists, we don’t feel that our struggle is only for us, we acknowledge the intersectionality: gender, class, race, and more.”

The chance for solidarity in fighting the system, however, does not mean there aren’t opportunities for change within the Latino community itself. “We must take advantage of this situation to look at ourselves as well. We have a colonized mentality embedded in the unconscious,” Rovira says. “The oppressed people are trained to justify oppression and their oppressors. We look down on our own people.”

Rovira recalls that “salsa [in New York] was demonized because it used drums and the drums reflected our African ancestry, but no one wanted to be Black. People told me we are trigueños and I asked them to show me on the map where trigueños are from.” This is why Rovira emphasizes that now it is also a good time to examine racism among Latinos.

The key, Rovira said, is to study the past as well as the present. “All oppressed people have not been trained to think critically, but being able to become critical thinkers is the only way,” Rovira said.

“You don’t need to be able to read. Critical thinking is the opposite of accepting,” Rovira concludes.

One thought on “Former Young Lords Reflect on Protests, Racism and Police Violence”

The Young Dummies most have sucked because the broke up so fast 😍