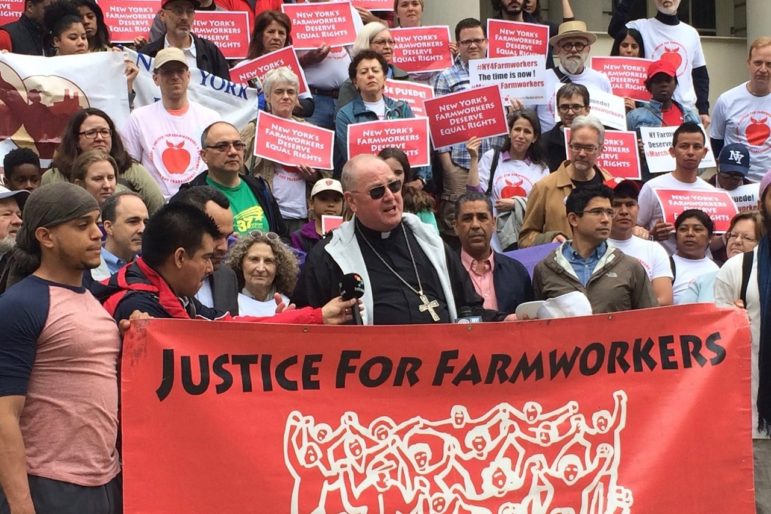

Justice for Farmworkers

With a Democratic-controlled State Senate and Assembly, many advocates are hopeful that this will be the year the Farmworker Fair Labor Practices Act finally passes.

On two fronts this year, farmworkers in New York might see their legal position improve.

The Farmworker Fair Labor Practices Act, which was introduced in the State Assembly and the Senate, would grant New York farmworkers protections that virtually all other workers in the state have, including the right to collective bargaining, overtime pay and a day of rest.

Simultaneously, an appeal in a lawsuit led by a former dairy farm worker argues that a law exempting farmworkers from organizing rights violates the state constitution. The state Appellate Court heard oral arguments from NYCLU lawyers on Monday and a decision is expected in the coming months.

Farmworkers in New York are excluded from labor protections under legislation that dates back to the passage of the Federal Labor Relations Act in the 1930s. In order to get approval from Southern Democrats, the New Deal-era law excluded agricultural and domestic workers—who were largely Black—from federal labor protections. New York State’s version of the law, passed in 1938, followed suit.

Though a bill to remedy that exclusion has been passed in the Assembly many times—the push for New York farmworker protections dates back more than 20 years—it has never passed the State Senate due to opposition from some Republican senators and the New York Farm Bureau, an industry organization.

The last time the bill came to a Senate vote was in 2010. It lost by three votes.

Now that there is a Democratic-controlled State Senate and Assembly, many advocates are hopeful that this will be the year the bill finally passes.

“We’re cautiously optimistic,” says José Chapa, an organizer with Rural Migrant Ministry, a worker advocacy organization that has fought for these protections since the 1990s.

Rural Migrant Ministry and other members of an advocacy coalition that includes the NYCLU are conducting a series of town halls around the state featuring experts on labor and farmworker issues in the coming weeks. They also plan to hold meetings with legislators.

“We are hoping to be civil. We’re hoping to bring attention to the issue and hoping that new senators get educated on the issues if they’re not already,” he says.

The bill will likely pass the Assembly, where it was introduced by Queens Representative Cathy Nolan, who has been a champion of bill since 2010. In the Senate, where it was introduced by the newly-elected Jessica Ramos, it has the support of 22 co-sponsors, including Deputy Majority Leader Michael Gianaris, but it doesn’t appear to be one of the Democrats’ legislative priorities heading into budget season.

In both the Senate and the Assembly, the bill has been referred to the labor committee, where in the Senate, it has died in the past.

“We don’t expect it to move fast,” says Chapa.

Lisa Zucker, a legislative attorney with NYCLU, says she’s optimistic because she knows the bill has the support of the governor.

In 2016, when the suit now in appeal was originally filed, Governor Andrew Cuomo said he supported farmworkers’ right to organize, and his administration declined to defend the state in court. (The Farm Bureau took up that duty instead).

A victory in the suit—which is led by plaintiff Crispin Hernandez, who was fired from his dairy farm job after meeting with labor organizers and other workers, and two worker organizations—would simply grant farmworkers collective bargaining protections, nullifying their exemption from the State Employment Relations Act (SERA) and granting them the protections almost all other hourly employees are entitled to.

Passage of the legislation would go slightly further than a lawsuit victory. In addition to establishing a 40-hour workweek and overtime pay, the bill includes provisions that would create a sanitary code for housing, make farmworkers eligible for workers’ compensation benefits and require the reporting of injuries.

In 2010, the state passed legislation that gave domestic workers similar protections—though their exemption from SERA is still on the books. States such as California, Colorado, Hawaii and Maine give farmworkers overtime pay. Others, including Arizona, Idaho, and Wisconsin, give farmworkers collective bargaining rights.

Primary opposition to the legislation is likely to come, as it always has, from the Farm Bureau, which has argued that farms should be exempt because of the unique nature of agricultural work and the precarious state of farms, as well as farm-country constituents. This year, with dairy farmers facing the challenge of low prices, their argument may still have sway.

Zucker says that argument is bogus; We shouldn’t support one industry on the backs of violations of 100,000 workers’ basic rights, she says.

“Frankly, in 2019, it’s an embarrassment that 80 years later, we’re talking whether our most vulnerable workers receive the most basic labor protections that almost every other hourly worker enjoys,” she says.