David Brand

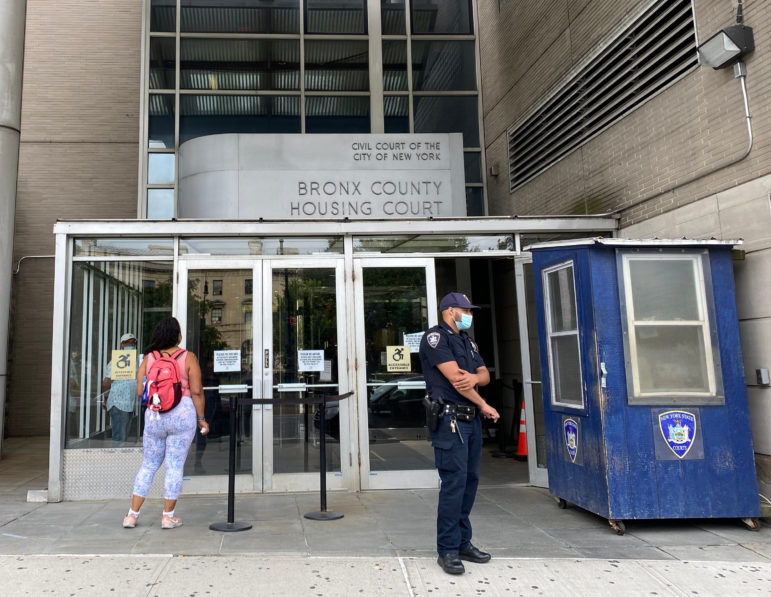

Bronx Housing Court on Aug. 16, days after the Supreme Court struck down a central part of New York’s COVID eviction moratorium.

Nursing home aide Ruth Ortiz stood outside Bronx Housing Court at 9 a.m. Monday clutching two bags of housing documents, including her rental assistance application number and email print-outs proving her correspondence with the management company that runs her building.

Ortiz said she owes about $3,000 in rent dating back to late last year, when she fell behind after missing a month of work because she had COVID-19. Her employer cut her hours and she has struggled to catch up on her arrears, she said, but she filed for aid through the state’s $2.2 billion Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP) in early June. She, like many others who applied for the rent relief, is still waiting.

On Saturday night, however, she received a notice from her LLC landlord informing her that they planned to start eviction proceedings. Ortiz said she thought she had done everything right to avoid eviction and make her landlord whole. The property owner and management company did not respond to requests for comment.

“It’s very confusing,” Ortiz said. “I don’t want them to drop me out of the apartment.”

Ortiz’s notice arrived two days after the U.S. Supreme Court blocked a key piece of New York’s eviction moratorium, giving property owners a chance to argue their cases against tenants who owe back rent in housing court. The decision has added another layer of fear and frustration for tenants, landlords and their representatives as they contend with the state’s ongoing eviction rules.

The high court ruling Aug. 12 specifically struck down a provision in the state law that allowed tenants to use “financial hardship declaration forms”—sworn statements that they were financially impacted by the COVID crisis—as an automatic defense against eviction. Housing experts say the ruling cut to the core of the eviction ban, but is not likely to fuel an immediate surge in evictions because cases take months to resolve, and housing courts are already strained. But they say it will likely lead to an uptick in new filings and force more and more tenants to visit court in-person.

“It will be a gradual uptick,” said BronxWorks Assistant Executive Director Scott Auwarter, whose office overlooks the line outside Bronx Housing Court. Prior to the pandemic, hundreds would queue up along Grand Concourse to enter the court and judges held hearings in elevator bays. On Monday morning, there were never more than 10 people waiting to enter and speak with a clerk.

“When you see that line stretch down the block and wrap around the corner, you’ll know things are back to normal,” Auwarter said. “It’s going to snowball at some point and it’s going to start rolling down the hill. We’re expecting a surge.”

The state’s Office of Court Administration (OCA) said there were 182 eviction proceedings filed citywide on Friday, the day after the Supreme Court ruling, and two more Saturday. The exact number of eviction cases in New York is hard to pin down because many tenants and landlords resolve their issues out of court. Before the state imposed coronavirus restrictions in March 2020, there were 130,000 pending eviction cases in New York City, but only about 50,000 of those were “actively litigated eviction cases,” according to OCA.

More than 830,000 New Yorkers, including 512,063 in New York City, owe rent arrears, according to researchers at the policy group National Atlas Equity. For hundreds of thousands of them, help should be on the way. It’s just taking a while.

The state’s beleaguered Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP) has gotten off to a rocky start, adding to the confusion for tenants and landlords. Property owners whose low-income tenants owe rent from the pandemic months can receive up to a year of back rent, plus three future months, from the federally-funded pot of money.

Landlords who seek reimbursement through ERAP agree to house their tenants for at least another year, but checks have only just started reaching some owners. As of Monday, OTDA has distributed 8,305 payments to landlords totaling more than $114.1 million, the agency said. That’s still just about 5 percent of the total fund since applications opened June 1. OTDA says another roughly $500 million is earmarked for specific qualifying landlords.

Under federal guidelines, states must distribute 65 percent of the rental assistance funding by Sept. 30, a deadline state officials have sworn they will meet, despite the slow rollout so far.

Bogdan Manescu, a property owner in Holbrook, NY, is among those who has so far been paid—though the program still only covers about two-thirds of the debt.

He was due $45,000 from a tenant who stopped paying his $2,500-a-month rent in March 2020, his application shows. Manescu worked with the tenant to apply for ERAP funding, and said he received a $30,000 payment Monday. However, the state declined to give him three future months of rent on behalf of the tenant. Under the terms of the program, Manescu must continue renting to the tenant for another year, even if the tenant fails to pay rent.

“There is $15,000 left to cover the rest, but it’s good to get something rather than nothing,” he said.

Then there’s the federal eviction moratorium, which covers counties with high rates of COVID transmission—a shifting criteria—and lasts until Oct. 3. The moratorium has so far withstood legal challenges, but that could change immediately if the Supreme Court decides to weigh in there as it did on New York State’s eviction ban.

“Much like the last year and a half, there’s a lot of unknowns,” said tenant attorney Justin La Mort, a supervisor at the organization Mobilization for Justice. “And that’s an uncomfortable situation for anyone worried about losing their homes.”

READ MORE: What the Supreme Court Decision Means for NY’s Eviction Moratorium

Landlord groups have welcomed the Supreme Court ruling, especially for the impact it could have for small property owners struggling after months without steady rent payments—or any revenue at all.

Some landlords say they are weighing whether they will pursue an eviction against tenants who have created dangerous conditions during the pandemic, even if that means forfeiting unpaid rent they could recoup through ERAP.

Cynthia Brooks owns a four-unit building in Brownsville and declined to renew the lease for one family in December 2019, giving them until February 2020 to find a new home. That type of eviction is known as a holdover case.

A judge gave the family, a mother and a teenage son, until June 2020 to leave—but then the pandemic triggered the first moratorium, enabling them to stay in place. Brooks said the mother stopped paying rent before moving out and leaving the 17-year-old alone in the home for months. The teen, now 18, frequently hosts parties, where guests have broken into a vacant unit, she said. Photos show holes in the walls and garbage piled up in the unit and the hallway, attracting rats and roaches, which invade other apartments, Brooks said.

She said she thinks the Supreme Court’s decision might allow her to renew the eviction order issued by the judge back in 2020, but she doubts she will be able to reclaim possession of the unit anytime soon.

“There are so many twists and turns with this story. You think you’re taking one step forward, but you’re taking two steps back,” she said, adding that the backlogged courts could delay the case for months. “There are pre-COVID cases they didn’t want to dispose of. You’re talking about fall 2022.”

The Supreme Court decision is also intensifying an ongoing battle in Albany. Republicans and some moderate Democrats have sided with property owners and want to leave the moratoria behind. Progressive lawmakers, including many in New York City, want to tailor the state’s COVID-19 Emergency Eviction and Foreclosure Prevention Act (CEEFPA) to satisfy the court’s ruling.

In a statement Monday, State Sens. Julia Salazar and Jabari Brisport, and State Assemblymembers Phara Souffrant Forrest, Marcela Mitaynes, Zohran Mamdani, and Emily Gallagher said “allowing these tenant protections to lapse will threaten the safety and security of hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers.”

They called for lawmakers to convene for an emergency session in order to pass a new state eviction ban that would hold up to the Supreme Court’s ruling, and extend to June 2022.

“If we do not act, we will witness nothing short of an eviction crisis as the dangerous Delta variant spreads rapidly through our communities,” they wrote. “We cannot allow a politically motivated Supreme Court decision to prioritize landlords’ profits over the health and safety of our constituents.”

Incoming Gov. Kathy Hochul said Thursday that she will work with the legislature to adjust the current moratorium. “No New Yorker who has been financially hit or displaced by the pandemic should be forced out of their home,” Hochul said in a statement.

Outside Bronx Housing Court, laundry technician Kweku Annan took off work to wait on the short line. He said he received an eviction notice Thursday, hours before the Supreme Court decision, and owes his landlord about $7,500. He couldn’t pay rent after he was furloughed last year, he said.

He said he has heard of ERAP, but has yet to apply. The application is online-only, but his computer is broken. He learned that BronxWorks, next door to the courthouse, has contracted with New York City to help Bronx residents apply for the rental assistance.

Annan said he would likely visit the nonprofit provider to get some help navigating the process so that he can stay in his home with his son.

“I don’t have anywhere else to go,” he said.

8 thoughts on “Supreme Court Ruling on NY Eviction Ban Fuels Confusion For Tenants and Landlords”

The (erap) can also help you by phone because when I had trouble trying to do the application on line, it didn’t work and I gave up after trying about 5 times but then I called and got someone who actually wanted to help me mind you that I called 3 times and one of the operators was rude and one that wasn’t trying to do anything. But just hang in there.

The current policy is not working. The COVID RELIEF program is very one side with tenants in control. Many refusing to even fill out the paperwork, while others are taking advantage buying news cars and TVs. Landlords are the only business required to continue providing services for free while also trying to maintain the properties and pay mortgages and taxes. Many of us are struggling, on the verge of foreclosure, without assistance from the state or federal government that continue extend these mandates. It’s time for our representatives to understand there needs to be a direct payment program or tax/mortgage credits for landlords because if we go under, tenants are still going to lose their housing.

Landlords trying to evict tenants isn’t always about hardship or not being able to pay the rent. I have a tenant who has violated the rules in the rental lease and has gone in multiple mailboxes. No one should have to live like this. In addition keeping her there is interfering with the process of adopting my son. My oldest daughter and grand daughter will move down stairs to free up a room for my son. What am I to do? Would they rather a young child loose the only family he knows because of space or open court to evict someone who would eventually have to leave.

I have tenants who have thankfully paid their rent. They have violated the lease in other ways though. I am trying to sell the house and now they have changed the locks and will not allow access to show the house. Let me EVICT them so I can move on with my life.

I own a two family home in Altamont NY. I bought this home in 2004 for my family to live on one side and to operated my business on the other side. After a life changing event, the death of my teenage son and eventually getting divorced. I decided to move out of my home and rent it out. Long story short, I rented to a family, he was former military, but unemployed, the wife had a decent job and could support the family. Right from the beginning they were a problem. I tried very hard to get them to abide by the lease and pay the rent on time. It was a battle every month. This was before Covid. After months of frustration, I decided it was time to for them to go. Covid hit, I couldn’t evict. The rent payments stopped, the abuse started, physically and verbally, the last time I was able to inspect, the place was a disaster! How can someone live in such filth and show absolutely no respect for someone else’s property! They currently owe over $16,000 in rent. I’m forced to support a family fully capable of supporting themselves, but they don’t! Why, because the moratorium protects them from eviction at my expense! They don’t have to prove hardship just claim one and like magic they live for free! Meanwhile I’m on the verge of bankruptcy and losing my family home because of these scammers and the moratorium! Enough is enough! If you truly are experiencing a hardship, you must prove it. If you can’t then pay the rent or get the F&$k out! It’s not my responsibility to support your family. I’ve lived my life by the “golden rule” scammers live there life by the hurray for me and F&$K you rule. It’s time to hold these scammers accountable!! Make them pay. Hard working honest taxpayers shouldn’t have to pay the rent for them!

Well said!

Absolute truth!

I’m a property manager and real estate sales person in Buffalo, NY. We’re dealing with very similar situations! Enough, is definitely enough!!!

The tenants who are truly struggling (and there’s a few), seem to be more willing to hand over a few dollars towards rent than the folks that are working full-time and taking advantage!

I see new clothes, new shoes, new handbags, new hairdos, new nails, new TVs, new furniture etc. but they’re scamming!

They’re taking from the folks that actually need it, as well as taking from the landlord who also has responsibilities to answer to…kids, wife, mortgage, ins etc.

I’m so done with this BS! These lazy folks need to get up their bums, get a job and remember what it means to go to work everyday.

The sheer ignorance is mind blowing.

Most landlords don’t want to do evictions. It’s expensive and stressful but it’s the only tool. Considering the huge failure of the program to date it would help if court was open. Both parties would be before a judge and for those renters that qualify for ERAP, or One Shot Deals, it could be done there in court. For those renters that don’t qualify the judges can hear those cases. We cant have a healthy housing market without the courts.

I’ve been trying to apply for erap for quite some time now, I’m really backed up I’m my rent and need help paying it I have a difibrillator in my heart and a fistula in my wrist waiting for a dicition on dialysis, in other words I won’t be able to work anymore, I’m desperately try to get this program to help me.