Sadef Ali Kully

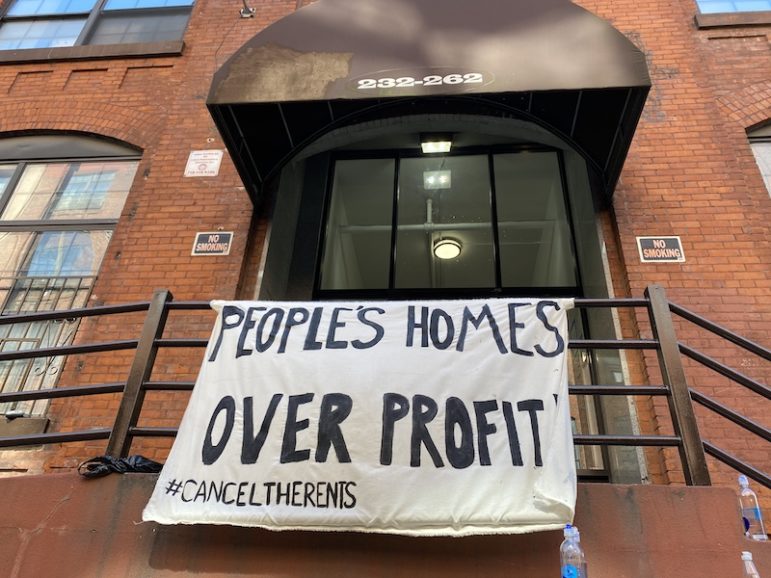

A sign protesting rent collections in Brooklyn during the height of the Coronavirus epidemic.

The U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday struck down a key piece of New York’s eviction moratorium, blocking a provision that allowed tenants to fend off Housing Court proceedings by swearing they had experienced a COVID-related financial hardship.

In an unsigned decision, the country’s highest court sided with a group of New York property owners who challenged the state’s COVID Emergency Eviction and Foreclosure Prevention Act (CEEFPA), which has frozen nearly all evictions in the state since December 2020. The legislation, set to expire Aug. 31, has enabled tenants to effectively halt eviction proceedings by submitting a hardship declaration form—a newly created document attesting to the economic impact of the pandemic on the applicant’s ability to pay rent.

The court’s conservative justices ruled that the “scheme violates the Court’s longstanding teaching that ordinarily ‘no man can be a judge in his own case’ consistent with the Due Process Clause.”

The decision specifically applies to tenants who’ve submitted that hardship declaration form to stay out of housing court, allowing them to self-certify financial hardship and which “generally precludes a landlord from contesting that certification and denies the landlord a hearing,” the court’s order explains. The ruling leaves in place the state’s Tenant Safe Harbor Act, which allows tenants to use a COVID-19 hardship defense in housing court and temporarily prevents evictions for tenants whose landlords commenced nonpayment proceedings during the pandemic.

The court’s three liberal justices dissented from the majority opinion, with Justice Stephen Breyer writing that the decision puts New Yorkers at risk of “unnecessary evictions” and citing the slow rollout of the state’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP). The state’s Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance (OTDA) has so far issued less than 5 percent of the state’s roughly $2.2 billion ERAP relief fund to landlords whose low-income tenants could not pay rent during the pandemic.

“While applicants correctly point out that there are landlords who suffer hardship, we must balance against the landlords’ hardship the hardship to New York tenants who have relied on CEEFPA’s protections and will now be forced to face eviction proceedings earlier than expected,” wrote Breyer, who was joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan. “This is troubling because, as noted, New York is in the process of distributing over $2 billion in federal assistance that will help tenants affected by the pandemic avoid eviction.”

Breyer also said the court was interfering with the powers of the state’s legislative branch to set policy. “The New York Legislature is responsible for responding to a grave and unpredictable public health crisis,” he wrote.

More than 830,000 New Yorkers owe back rent, according to researchers at National Atlas Equity, a policy group affiliated with the University of Southern California. In a statement, incoming Gov. Kathy Hochul—set to take over the governorship at the end of the month following Andrew Cuomo’s resignation—said she would work with the legislature to shore up the current moratorium.

“No New Yorker who has been financially hit or displaced by the pandemic should be forced out of their home,” Hochul said.

Tenant advocates say the ruling is a crushing blow to renters and will force thousands of New Yorkers to head to housing court to try to combat eviction proceedings. Advocates and several lawmakers have been urging the state to extend current eviction protections until ERAP money reaches more landlords. “We’re going to see massive evictions,” said Ellen Davidson, a staff attorney in Legal Aid’s housing division.

“There are cases that are keyed up and just waiting for the end of the eviction moratorium,” she said Thursday evening. “I think those notices could go out tomorrow, which means tenants who want to stop the evictions have to rush to court tomorrow.”

New eviction cases typically take months to resolve, but tenants who faced eviction just prior to the pandemic moratorium are at particular risk of losing their homes. Many landlords will likely seek to renew eviction orders that have expired.

Davidson urged tenants facing eviction to secure an attorney under the city law that gives renters the right to a lawyer in housing court. Renters represented by a lawyer in housing court are far more likely to prevent an eviction than clients without counsel, numerous studies have shown. Tenants who receive an eviction notice can call 311 and ask to connect with a lawyer, she said.

In a statement, Legal Aid said tenants “have suffered immensely during COVID-19 [and] will have no trouble proving hardship and satisfying the supreme courts’ mandate.”

The property owners who challenged the state law were represented by the landlord group Rent Stabilization Association, which hired attorney Randy Mastro, a former deputy mayor, to argue their case. Mastro praised the court’s decision in a statement Thursday.

“New York recently reopened in all other respects, yet its eviction moratorium remained in place, barring the courthouse door to landowners unable to gain access to their own properties from holdover tenants, many of whom haven’t paid rent for the past 17 months,” Mastro said.

But Jay Martin, the executive director of the rent stabilized landlord group Community Housing Improvement Program, said he did not consider the ruling a “victory.” The decision simply means property owners will have a chance to have their cases heard in court and gain leverage in nonpayment or other tenant disputes, he said.

“It’s what we always said from day one: The eviction moratorium helps no one pay their rent, pay their mortgage, or pay their property taxes and what we need to focus on is get rent relief out the door,” Martin said. “We stand ready to work with tenants, property owners and government officials to make sure there isn’t a wave of evictions.”

Martin said he is advising landlords not to rush to file evictions and instead wait for the state to release more ERAP money—though he has pressed New York officials to distribute the money much faster.

“I tell them that if someone didn’t have money to pay rent yesterday, they’re not going to have money to pay rent tomorrow,” Martin said. “You’re going to be left with an empty apartment and you’re not going to get the back rent.”

Two lawmakers have introduced a bill to extend the state’s eviction moratorium, and advocates are now urging the legislature to reconvene and adjust the hardship form rules to fit the Supreme Court’s ruling.

Manhattan State Sen. Brian Kavanagh, who sponsored CEEFPA last year, told City Limits that lawmakers would “see if there’s a way to shore up the moratorium by taking action consistent with what the Supreme Court has said.”

He criticized the justices for potentially exposing potentially hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers to the close confines of housing courts amid a surge in COVID cases.

“It’s a basic public health measure and we think it was in the powers of the legislature given the pandemic. It’s disappointing that a majority of the Supreme Court disagreed with us,” he said. “There are hundreds of thousands of households that are now in danger. And it’s not just a danger to those households. It’s a danger to all of us.”

Kavanagh said state lawmakers would work with OTDA to streamline ERAP payments.

“It needs to be making payments at a much larger scale and more rapidly than it has been,” he said. “The ultimate protection for a tenant is going to be having their rent paid.”

20 thoughts on “What the Supreme Court Decision Means for NY’s Eviction Moratorium”

As a landlord of age 72, who doubled up mortgage payments before retiring, so my 2 rentals could be paid for, I have been hardhit by the pandemic also. Because there are no mortgages on my property, I am not eligible for mortgage money on the houses, and there has been no word on erap, which my tenant applied for, but lied profusely when he said the house was his primary residence, and said he was unemployed when he, in fact, was working full-time right along and never was sick, making him ineligible to get help for me through that program. He knows he can’t be evicted or taken to court, so has not paid five cents toward rent since Oct. 2020. In March 2020, I lost my part-time job correcting SAT essays, because the pandemic eliminated any offering of the SAT test, but I was also ineligible for unemployment (self-employed contractor), so planned to rely on rent from my two tenant houses for income. I have continued to pay the taxes and maintenance on one rental in which the tenants have done almost $6,ooo worth of damage, and have not paid a nickel of rent since October 2020, all while working full-time, and at times, renting out the house Air B and B, even though the lease prohibits subletting (but he knows I can’t take him to eviction court, and just laughs and says “What are you going to do, evict me?” when I tell him it’s a lease violation and he’s responsible for damages they cause.). When the moratorium was lifted temporarily, I had the tenant served papers to get out, but the tenant filled out papers self-certifying they were hurt by Covid, but he didn’t have to submit anything else to prove it, and it was nothing landlords could contest, so the tenant was able to avoid eviction court, and is living in the house with their friends, party every weekend, holes in the wall, painting the 15′ by 24′ livingroom walnut hardwood floors bright orange, and the entire bathroom, even the fixtures, flat black after a lease that clearly says “no painting…”so my income has dropped about $15,000 from the loss of my job (no un-employment), and loss of the rent (about $10,000) which I expected to get from the house in rent; In addition, I will have to do $6,000-$7,000 worth of repairs just to make the place rentable again if I can ever get the tenants out. This house was my parents’ house, saved and paid off for retirement income; however, the government has effectively seized that income and forced me to provide social services (free housing) to deadbeat property-destroying working tenants for almost a year, because they enacted laws to prohibit me from taking them to eviction court.. No one should be forced to keep other unrelated families for free, especially when the tenant has multiple lease violations, does pay ANY rent, but they know they can’t be taken to court and evicted; all they have to do is say “Covid” and they continue to get free rent at my expense, sublet the house to others for their economic gain, while I continue to have to pay the property taxes and for plumbing and other repairs caused by misuse. Let the moratorium end, or at least allow all tenants to be taken to court. If tenants truly are hard hit by Covid, judges should order them to get help from SOCIAL SERVICES, not force private citizens to provide free housing at the landlords’ own private expense. Free housing is what social services is for, and what landlords pay property taxes for. As a 72-year-old retired diabetic, with eyesight problems, few jobs are open to me, and I planned to be able to support myself with the investment I made in these houses; instead, I will probably lose my own home, because I can’t afford to pay the taxes and repairs on my own house now, and can’t sell the tenant house either if the tenants won’t move (most people want a house to live in, and not buy to rent to a deadbeat already in it, who can’t be evicted). Mandating private landlords to provide free housing was unfair when it was legislated; so was exempting tenants from having to go to court to prove they were hit with Covid; but extending the moratorium any longer decimates and penalizes those landlords who worked hard to own their properties free and clear, as retirement income, and now see their retirement income stripped from them by laws penalizing them for owning property (and ineligible for help because they own property). Free housing and help paying rent is social services’ job, but somehow our government has foisted that job and expense on the property-tax paying landlords! Extremely unfair, and I will never vote for any legislator or governor who thinks forcing private landlords to provide social services at their own private loss is okay, Providing housing or rent should be the purview of a tax-supported social service agency, not private taxpaying property owners who depend on rent for their own income. End the moratorium, and allow landlords to gain control of the property they are paying taxes on; the government had no right to seize their property for its own use to provide the social service of free or severely reduced housing , and it’s high time they return control of it to those who bought the property for their own use or income, maintained the property, and paid all repairs and taxes on the property. And landlords need to vote AGAINST any legislator who thinks continued government seizure and control of private property is okay for government use before seizing people’s property, guns, vehicles, or anything else becomes a government habit when legislators want to do that.

Totally agree. Well stated. The conversation is being dominated by Renters who like not having a Housing expense. There are Signs all over for service industry jobs paying the new NYS minimum of $15/hour, that they can’t find applicants for. It’s like someone wants the only Housing available to be Federally subsidized Apartment buildings

Private property rights are guaranteed in the US Constitution. NYS is basically forcing private property owners to provide free housing for renters unable to pay their rent. Just wait till the Supreme Court finds all of NYS ‘renter protection’ laws unconstitutional. Maybe even all rent stabilization laws will be thrown out too.

August 14, 2021 – NYC:

RE: Tenants and Landlords Need to Work Together and our Government needs to implement real solutions, not useless talk and putting temporary band aids on this urgent matter. Millions of People are at serious risk of losing their lives and homes.

In response to this article and your comment, as a renter, I believe all Landlords and Property Owners should be paid. However, in consideration of the current circumstances with this awful Covid 19 pandemic, and now the new Delta variant spreading rapidly, evicting People in any part of our Country will not help anyone. It will only make things worse. What the Government needs to do is direct those relief funds directly to affected Landlords and Property Owners to make sure they are covered, and allow Tenants who are seriously affected by this Pandemic to get back on their feet. Because the red tape, and awful delays in getting money into the hands of tenants / renters who risk eviction is clearly not a good working solution, when only a very small portion of those monies has been used to help Tenants in need.

We believe there is a much better way, just like my boss said, if the Government distributes the Tenant rent relief monies directly to Landlords and Property Owners with non-paying Tenants, that would help everyone, and this entire issue can be neutralized. If there is a will between all sides, there is a way to work together, and for the sake of all Humanity and everyone affected, we should find common ground on this, because lives are at stake, and LIFE is far more valuable than any material thing on Earth.

Let’s not forget, without LIFE, nothing in this world has any value, meaning or purpose.

Also, no one’s rights should be disregarded or ignored. Not the Landlords or the Tenants, but under these current circumstances, we all need to find common ground on this urgent issue, and there are many ways we can work together to solve this life threatening crisis between Landlords and Tenants. Real solutions are available, and both sides deserve real solutions from our Government, and each other, not just words and red tape. We all need to work together to address this urgent problem.

Last and most importantly, we need to help each other, and lift each other up from this crisis, so we can all truly recover from this pandemic, and the enormous damage its done to so many lives around the world. We can overcome these challenges, and work TOGETHER! Humanity can do better.

Thank you for sharing. Stay safe and God Bless all!

Sophia

Supreme Court won’t overturn the Moratorium until they feel safe that they won’t bring on an Impeachment investigation for voting the wrong way. They now weigh how each outcome will effect their once “life-time” appointment because they know they can and may be removed as long as the Dems hold a majority. Some Dems have already asked the AG Garland to continue / re-open the Kavanaugh hearings to try and impeach him. Schumer has already threatened more then one of them (which he later claimed was mis-speaking).

I’m small landlord with one 2 family house and my tenant has not paid since December 2019 and have multiple unknown people living in the apartment since Nov 2019. We gave everyone notice to vacate through lawyer to leave the house by April 2020 but the unknown people still here till today. So far I’ve lost 40k $. My holdover saw is waiting in court since Feb 2020. Where is justice for me?

I have a similar situation. My tenants have no loss of income and collect rent from the several bodies they have living in they’re house. They lied to their new lawyer. Tried to get rig up stuff in the house so it would be deemed u inhabitable, so they wouldn’t owe all the back rent. But they checked that box on the NY Covid Hardship form. And they get to live for free. I have to pay the triple utilities. The beautiful home they moved into 22 months ago, with a 6 month lease, they broke looks horrific. They made a fraudulent lease for someone to collect welfare money. To live in the home. I told them to leave, started eviction , 2/2020. They should have moved 3/2020. Nope, they refused any type of my attempting to work things out. I’m so sick. They keep trying to. get me in trouble for anything they can try to pin on me. Call the sheriff regularly claiming stupid stuff. And there aren’t any repercussions. I cannot afford to pay another winter for them. I need to be allowed to challenge their bogus hardship. If they allowed NY landlords with tenants taking advantage of this, it would be a compromise in my mind. It’s gone on too long. I am losing my mind because there isn’t help fir me because they won’t qualify. It’s just way out of hand.

Sick people in our government right now. I want to know who in government is gonna let these people move in their homes for free ? It’s a crime to take away someone’s pay. I’m sure they all got paid during Covid. Let the tenants prove they can’t pay …,. We personally had 4 that lied and took advantage. I think it’s time to put a moratorium on all taxes.

This is shameful that the government is not even letting landlords have a say in court. I do understand some people need help but prove it!! My Father died and invited a freeloader in the house I can’t evict. She has never paid a dime for years. I have to pay all my deceased Father’s debts. I can’t even sell his home because of this eviction Moratorium. NY has picked a choose parts of the pandemic. Opening up but can’t evict deadbeat people.. Give me a break. Im will never vote for anyone who thinks this is okay!! Ever!!!

August 14, 2021 – NYC:

RE: Tenants and Landlords Need to Work Together and our Government needs to implement real solutions, not useless talk and putting temporary band aids on this urgent matter. Millions of People are at serious risk of losing their lives and homes.

In response to this article and all comments, as a renter, I believe all Landlords and Property Owners should be paid. However, in consideration of the current circumstances with this awful Covid 19 pandemic, and now the new Delta variant spreading rapidly, evicting People in any part of our Country will not help anyone. It will only make things worse. What the Government needs to do is direct those relief funds directly to affected Landlords and Property Owners to make sure they are covered, and allow Tenants who are seriously affected by this Pandemic to get back on their feet. Because the red tape, and awful delays in getting money into the hands of tenants / renters who risk eviction is clearly not a good working solution, when only a very small portion of those monies has been used to help Tenants in need.

We believe there is a much better way, just like my boss said, if the Government distributes the Tenant rent relief monies directly to Landlords and Property Owners with non-paying Tenants, that would help everyone, and this entire issue can be neutralized. If there is a will between all sides, there is a way to work together, and for the sake of all Humanity and everyone affected, we should find common ground on this, because lives are at stake, and LIFE is far more valuable than any material thing on Earth.

Let’s not forget, without LIFE, nothing in this world has any value, meaning or purpose.

Also, no one’s rights should be disregarded or ignored. Not the Landlords or the Tenants, but under these current circumstances, we all need to find common ground on this urgent issue, and there are many ways we can work together to solve this life threatening crisis between Landlords and Tenants. Real solutions are available, and both sides deserve real solutions from our Government, and each other, not just words and red tape. We all need to work together to address this urgent problem.

Last and most importantly, we need to help each other, and lift each other up from this crisis, so we can all truly recover from this pandemic, and the enormous damage its done to so many lives around the world. We can overcome these challenges, and work TOGETHER! Humanity can do better.

Thank you for sharing. Stay safe and God Bless all!

Sophia

New York, NY USA

You apparently are not one of the landlords that are supporting these free loaders….. We are not government that should be providing free housing for these people we are private home owners who if we did not pay our taxes our homes would be taken away from us, so now government is demanding we continue paying taxes or lose our homes, and the government has taken our homes anyway with taxes still being paid but not rents, we also have to pay for scam artists to live for free while we pay water, insurance, other utilities . There are many, many jobs available. When someone needs financial help from the government, they need to provide proof but these horrible people who are taking advantage and literally living for free in our family homes that my mom worked 15,16 hours a day as a waitress to pay for and we are going poor for STRANGERS to not only live in our homes at our expense but destroying our family homes. You say that landlords & tenants should come to an agreement these people do NOT respond they want ONLY FREE!!!!!!!! Government has taken away as Landlords our Constitutional rights to our own homes……..confiscated our homes for people who the government is responsible for while politicians not only are not affected by this but Don’t Care!!!!!

After 18 months of no communication NO RENT there is no agreement other than EVICTION. We have been through ENOUGH!!!!!!

TIME for LANDLORDS TO BE ABLE TO GET BACK THEIR HOMES!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Rose

SI NY

Once I evict all my tenants I will leave my f–king apartments empty so that I don’t have to deal with NYC rent regulations. I urge every landlord who can afford this should do it. Make this a crisis for tenants and city of NY to solve the issue. I also urge all landlords to stop paying NYC property tax and water bill and see how the city feels.

The NewYork blanket and blind eviction moratorium has pushed my family through hell. My tenants stopped paying and I lost 100% of rent income for the last 18 months, but yet they are too rich to qualify for ERAP. The tremendous frustration, the panic attacks, the depressions that I suffered from getting robbed every day from my property right has often led me to suicidal thoughts. I have been pushed against the wall and over the limit I can suffer. I wish one day those of you who did this, will experience the same horrible sufferings you heartless people put me and my family through. I am talking the cheating tenants who abused the system and those corrupt lawmakers who pretend to care about “public health” and rob small landlords to give to the thieves. You are robbers. And any deaths result from this suffering, are definitely caused by you, and for that you are murderers too! Remember that!!

If you or someone you know is experiencing suicidal thoughts, help is available. Call 800-273-8255 to speak with someone today or visit https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

The problem here in Albany is that many Young renters read ‘eviction moratorium’ and took that to mean ‘don’t bother to pay ANYTHING’. When stimulus checks came in they upgraded their smartphones. Non-corporate owner occupied homeowner landlords are struggling. Going to court means that renters must go on record and document what income they received. Jobs are coming back and people who don’t have a Housing expense aren’t trying to work. Give preference to those who made an attempt to pay SOMETHING. This is just settling up more gentrification as Older homeowners on Fixed/retirement incomes are forced to sell.

We are an owner occupied homeowner landlord of 2 family home. We are lucky that our tenants have been able to keep paying their rent. But many neighbors are not. Most homeowners here are in their 60s and on Fixed income from pensions and Social security. No real profit margin. Our mortgages were approved based on the anticipated rental incomes. Banks don’t want to hear about your loss of rental income. They just want the note paid on time. I am pass the age where I can get a job to make up the difference. So NYS is just saying tough luck?

My husband and I are the owners of 6 family house. 4 out of 6 apartments got into a coalition against us and stopped paying rent since September of last year. We already lost almost $100K on our building. Not only these people (if I can call them people) stopped paying rent, they harass us almost every time we are in the building. They scream, “Leave. You’re not welcomed here.” They also threat us and abuse. These “people” create damages and then call department of buildings on us. Since last year we got so many violations that we can’t even fix because tenants don’t let us in the apartments. We wanted to sell the building but tenants posted signs on their windows not to rent and buy from us. We already lost three contracts of sale.

Police also does not want to do anything. Just recently, when I was harassed and threatened by tenants, police told me not to knock on tenants doors because we’re in litigation with them. I always thought police is there to protect but not only they didn’t protect us, they didn’t say anything to tenants. Tenants continue to harass, threat and damage.

As an immigrant who came from Russia, always thought that there is no better country than America. I worked my way up and never even had thoughts of abusing the system. I still want to believe in good. Or I am just being naive.

The landlords HAVE THE RIGHT TO GET THEIR RENTAL INCOME — such rents which should be set by the NYS legislature in AN EQUITABLE MANNER (as the NYS LEGISLATURE, TO DIMINISH THE DISASTROUS EFFECTS CAUSED BY GENTRIFICATION, PASSED LEGISLATION FROM WHICH THE LANDLORDS/PROPERTY OWNERS BENEFITTED IMMENSELY: THEY INDEED HAVE RECEIVED IMMENSE SUMS OF PUBLIC FUNDS AT ADVANTAGEOUS, SMALL INTEREST RATES, SMALLER TAXES, ETC AMONG THE MANY OTHER LEGISLATIVE BENEFITS THEY OBTAINED TO BUILD SUBSIDIZED, AFFORDABLE HOUSING FOR THA LOW INCOE INDIVIDUALS AND THE POOR — such rents AN DUE TO THEM FROM THEIR PROPERTIES THEY OWN; YET The COVID-19 Pandemic has indeed brought up to light the increasingly looming HUMANITARIAN PROBLEM OF HOMELESSNESS AMONG THE WEAK, POWERLESS ELDERLY AND THE POOR IN NYCF caused by GENTRIFICATION WITH ITS SKY-ROCKETING, ABNORMAL RENT INCREASES (caused by the voracious greed of BOTH LANDLORDS AND THE POLITICIANS granting the landlords unjustified rent increases of 5% to even 15%!!) over all these decades of NEAR-ZERO TO ZERO%INFLATION. Those who were fortunate enough to obtain low-rent housing, WHO BY NOW ARE RETIRED, can still afford to pay rent on their small, fixed income, BUT NOT FOR LONG, because AS COSTS RISE AT AN ALLARMINGLY FAST RATE, THE RENTS ARE SKYROCK ETTING, MANY ELDERLY — and ironically MANY SMALL LANDLORDS — ARE ALREADY FORCED OUT OF THEIR HOMES: THE ELDERLY RENTERS EITHER PAY RENT (that is, IF they can still afford to pay it from their small pensions) AND THE ELDERLY LANDLORS PAY FOR REPAIRS OR ELSE BOTH OF THEM STARVE (let alone be able to afford to go to the doctor and buy medicines). You, landlords, CANNOT ESCAPE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE GENTRIFICATION PROBLEM BY WHICH YOU CAUSE THIS HUMANITARIAN PROBLEM OF HOMELESSNESS, ESPECIALLY AMONG THE WEAK ELDERLY (SMALL LANDLORDS AND RETIREES LIVING ON SMALL PENSIONS) AND THE POOR, AS LONG AS YOU, THE LANDLORDS’ LOBBY, PUSH MERCILESLY FOR SKYROCKETTING RENT INCREASES IN COLLUSION WITH CORRUPT POLITICIANS WHO GRANT THEM THESE ABHORRENT RENT HIKES, YOU, CORRUPT LANDLORDS, ARE EQUALLY GUILTY IN CREATING THIS HUMANITARIAN CRISIS BY YOUR ACTIONS OF GENTRIFICATION(imposing abnormally high rents) on the elderly and poor in NYC!!! ***AND ACTING IN AN ADVERSARIAL, CONTRADICTORY MANNER SUCH AS DRAGGING THE WEAK ELDERLY AND THE POOR IS DEFINITELY NOT THE SOLUTION!!!*** Now to solve the problem, all the stakeholders (the landlords, the renters, and the politicians) must cooperate to ensure the landlords get paid, the renters owing back rent and the small, impoverished landlords remain in their homes, — all New Yorkers living in peace under their own roofs.

No one likes to read all CAPS.

I am the owner of a 2 family home that I occupy one unit in. I am recently divorced and living on a single income. My tenants in the other unit stopped paying rent before the moratorium and I had served them notice to leave at the end of their lease, which was set to be up at the end of April 2020. Once the moratorium went into place, one of the tenants is a real estate agent and was very aware that they wouldn’t have to pay and couldn’t be evicted. I’m sure for a few months he had a hard time closing real estate transactions (though my guess is that since they weren’t paying even prior to COVID, he’s just not a very good real estate agent) but I’m more than sure he’s closed a few in the last 18 months at some point. If not, perhaps he should try a new career. His wife works and their adult child that lives in the unit also works. I haven’t received any rent from them since January of 2020. I am now owed roughly $40k while I continue to make mortgage, tax, insurance and utility payments on the house. The tenants bought themselves a new car during all this. The tenant applied for ERAP back in June. We are still waiting for the decision from ERAP. I have been calling once a week for the last month, with no updates available.

The fact that the only thing necessary to escape paying rent was a self-declaration form saying you have suffered hardship from COVID is insane. In what other circumstance can you put off owing $40k by just stating you are having a hard time financially WITHOUT ANY BACKUP OR CERTIFICATION OF HARDSHIP?

I get that there were people that lost their jobs due to COVID shutdowns and perhaps a few industries are still out of work. But it’s now been nearly 18 months. Most industries have been well more than open for quite some time. In fact, my place of employment is having a heck of a hard time finding strong employees to hire (they have multiple job offers) and this isn’t even restaurant or retail – this is financial services! The few friends I have in industries that are still in a bind (mostly live event production at this point) have shifted skills to take work elsewhere for now because who can be out of a job for 18 months? The moratorium should end at this point. ERAP program should be extended, and perhaps a law passed to push the landlords to work with tenants so everyone doesn’t get evicted at once. But as people above has mentioned, I’m not social services. My tenants have taken advantage of the situation and not had to prove financial hardship at all. They haven’t paid a penny. They haven’t even offered $100 a month!

To put a $40k burden on a single homeowner of a 2 family house is not acceptable. To those people who think that this is “big real estate” being greedy or whatever, you are completely wrong. I’m the one who is having to make difficult decisions about what to pay while my tenants get to live rent-free. How is that fair? This house is my only investment and again, my mortgage, taxes, insurance and utilities still have to be paid.

I am liberal in view but this particular situation has created a bigger problem than the original and needs to be fixed. And with the limited funding and delays in ERAP, the state isn’t doing enough to address it.