Gov. Kathy Hochul and Congressman Lee Zeldin have starkly different stances when it comes to energy policy and other environmental issues, at a time when New York is at a critical juncture in planning and implementing its ambitious plan to lower its carbon emissions.

Adi Talwar

Power stations in Astoria, Queens.

New York is at a critical juncture in its climate change goals. Four years ago, the state passed the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA), heralded at the time as one of the most aggressive climate bills in the nation, which requires New York to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions 40 percent by 2030.

How exactly the state will get there, if it does, is still being worked out—and will largely be in the hands of New York’s next governor, environmental advocates and activists say. The two gubernatorial candidates on the ballot in Tuesday’s election offer very different visions for New York’s climate policy future.

Incumbent Gov. Kathy Hochul, a democrat, has taken steps during her short time in office to move the state away from the use of fossil fuels, advocates say, like denying permits for three power plants whose plans were at odds with the CLCPA and requiring new cars sold in the state be zero-emission by 2030. She’s been endorsed by both the Seirra Club and the League of Conservation Voters, though some environmentalists feel she isn’t advancing policies as quickly or aggressively as the climate crisis demands.

Republican Lee Zeldin, by contrast, has decried many of the energy policies Hochul has advanced as out of touch and over-restrictive. While he’s advocated to protect certain natural resources in his home district on Long Island and is a member of a bipartisan climate group in Congress, he has a track record of voting often against environmentally-friendly legislation, most recently opposing the Inflation Reduction Act. He’s also called for reversing New York’s ban on gas fracking, to the dismay of environmental groups that pushed for years to secure the moratorium in 2014.

Tuesday’s election comes as New York’s Climate Action Council, the group of stakeholders charged with crafting a roadmap for how the state will meet its emissions reduction targets, is expected to issue its final plan by the end of this year. Getting it right, environmental advocates say, will be essential to staving off the worst impacts of the climate crisis in New York, already witnessed in extreme weather incidents like Hurricanes Ida and Sandy.

“The longer we wait, the more dire it really gets,” said Lee Ziesche of Sane Energy Project, an environmental group pushing for New York to convert fully to renewable energy. During an election cycle that’s been consumed by debates over public safety, it’s surprising that resiliency hasn’t taken a more prominent role, Ziesche added.

“Climate change puts us at such risk,” Ziesche said. “It will make New York unlivable. So, it should be a number one priority, and unfortunately it’s an issue that just keeps getting kind of kicked down the road.”

Fracking frenzy, pipeline protests

Zeldin, a former state senator and Donald-Trump backed Republican who’s been in Congress since 2015, doesn’t explicitly mention climate change among the six core “issues” highlighted on his campaign website. But his platform does mention energy policy several times, framing it as an economical issue. He calls for the state to approve more natural gas pipelines—something local environmentalists have been trying to stop—and for New York to begin fracking its own natural gas, a practice the state banned in 2014.

“If New York would reverse the Cuomo-Hochul ban on the safe extraction of resources under many parts of the state, jobs will be created, energy costs will go down, communities will be revitalized, and our state can prosper again,” the candidate said on Twitter earlier this year, a position he expanded on in an interview with the New York Times’ editorial board last month, where he said he would allow the resource-extracting technique in parts of upstate New York.

“Do we go to Iran and Venezuela and Saudi Arabia to ramp up their production? Because I guarantee you what we would be doing in the Southern Tier of New York is safer than what we are running off to to get them to rely on us,” Zeldin told the paper, calling himself an “an all-of-the-above energy guy.”

Environmentalists, though, say they’re alarmed by the prospect of a pro-fracking governor, citing the potential environmental and public health risks. “I think it’s an incredibly dangerous policy position to have,” said Alex Beauchamp, the northeast region director for Food & Water Action, which is supporting Hochul and publicly disputing Zeldin’s claims about fracking, saying the candidate is overstating the economic impact the practice has brought to other states that allow it.

It’s also unclear how Zeldin would legally go about reversing the state’s ban: While former Gov. Andrew Cuomo initially instituted the policy via executive order in 2014, the state legislature in Albany codified it in 2020.

“It would be a giant step backward at a time where we simply can’t afford to take one as a state,” Beauchamp said, saying Zeldin’s embrace of fracking and his support of natural gas amounts to climate denial in an era of rising sea levels and increasingly extreme weather. “This late, it is just nuts to not realize that we have to move off fossil fuels if we have any hope of a livable climate.”

Environmental groups have been pushing for New York to move away from reliance on natural gas in its energy sector, fracked or not. Earlier this year, Hochul came out in support of banning gas line hookups in new residential construction, similar to legislation passed by New York City in 2021. Supporters say it would help New York reduce greenhouse gas emissions from buildings, of which the state produces the most pollution in the country. The burning of fossil fuels in homes, like through gas stoves, has also been linked to negative health effects like asthma.

“Governor Hochul has really put us on a successful path of transitioning from fossil fuels to renewables…It’s really been a hallmark of her brief term as governor,” said Adrienne Esposito, executive director of the Long Island-based Citizens Campaign for the Environment. She pointed to the governor’s investments in battery storage technology, off-shore wind power and efforts to make it easier for residents to buy electric cars.

Zeldin, who represents Long Island, has criticized Hochul for some of those efforts, saying the zero-emission car requirements and building gas ban are part of a “far-left climate agenda.” Hochul’s campaign has countered by casting Zeldin as a “climate change denier,” a charge she lobbied in-person against the congressman during the lone governor’s debate last month on Spectrum NY1.

Screenshot/Spectrum News NY1

A screenshot of Zeldin and Hochul during last month’s debate on Spectrum News NY1.Zeldin’s campaign, and his congressional office, did not respond to City Limits’ questions for this story, including how the lawmaker would characterize his climate change beliefs (in 2014, then-Congressional candidate Zeldin told Newsday he was “not sold yet on the whole argument that we have as serious a problem as other people are,” according to Vice News.)

Esposito, whose organization has worked with both Hochul and Zeldin on environmental causes, said the Republican has been “a bit slow to get on board with climate change,” but that he’s been a vocal supporter of natural resources in his Long Island district, standing with environmental groups against the Trump administration’s efforts to expand offshore drilling (Zeldin was among many lawmakers of both parties who opposed the drilling in their home districts).

He’s also helped secure additional funding for the preservation of the Long Island Sound and was part of the the fight to keep Plum Island, a patch of land off Long Island’s east coast known for its abundant wildlife and plant species, from being auctioned off by the government (that last effort earned the congressmember a “Supporter of Nature” award from the The Nature Conservancy in 2015). “Those things were very beneficial to the environment and to the public,” Esposito said.

Zeldin’s campaign has touted that work as evidence of his environmental commitment. He’s also pointed to his involvement in a bipartisan group of federal lawmakers known as the “Climate Solutions Caucus”—though critics have charged right-wing elected officials of joining the caucus as a way to appear focused on popular issues, without actually advancing any climate-friendly legislation. Zeldin’s voting record on environmental bills earned him a dismal 14 percent on the League of Conservation Voters National Environmental Score Card (the average House member scored a 57).

Citizens Climate Lobby, a nonpartisan advocacy groups that lobbies federal lawmakers on climate issues and which pushed for the formation of the Climate Solutions Caucus, said Zeldin’s involvement in the group hasn’t translated to action.

“I have spent many years as a Citizens’ Climate Lobby volunteer encouraging Rep. Zeldin to step up on climate change, but unfortunately he remains woefully behind where I would like to see him,” Ashley Hunt-Martorano, who’s worked for the nonprofit since 2012, told City Limits in a statement. “New York deserves a governor who will not only acknowledge climate change but work aggressively to address it. Based on what I saw from his time in Congress, I’m not confident Lee Zeldin would be that governor.”

Sea change, or stalling?

When Hochul took office as governor in August of 2021, environmental activists said they were quickly heartened by her climate actions. During a little more than a year in office, her administration denied permits for three fossil fuel power plants across the state for being at odds with the CLCPA, green-lit two major renewable energy projects, upped the state’s goal for solar energy production and pledged to electrify New York’s fleet of school buses by 2035.

“There were some monumental accomplishments,” said Roger Downs, conservation director of the Sierra Club Atlantic Chapter, which has endorsed Hochul in Tuesday’s race, saying the new governor ushered in a “sea change” compared to resigned former Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s management style.

“Under Cuomo, everything was backlogged and everything had to be approved by him, when some of these things are timely and should be left up to the experts,” Downs said. “When [Hochul] became governor we saw sort of a logjam of environmental priorities get released.”

Julie Tighe, president of the New York League of Conservation Voters (which has also endorsed Hochul) pointed to the incumbent allocating an extra $1.2 billion to New York’s Clean Water, Clean Air, and Green Jobs Environmental Bond Act—a spending proposal that will fund a number of resiliency and climate infrastructure initiatives, which voters will have the option of approving or rejecting Tuesday.

“I think she really understands how pollution impacts our communities and is really prioritizing that, and she’s been putting her money where her mouth is,” Tighe said.

Still, some argue Hochul could be taking a more urgent approach to climate policy. “She came out pretty early and stopped the Astoria fracked gas power plant, but I think since then has really stalled on climate,” said Ziesche, from Sane Energy Project.

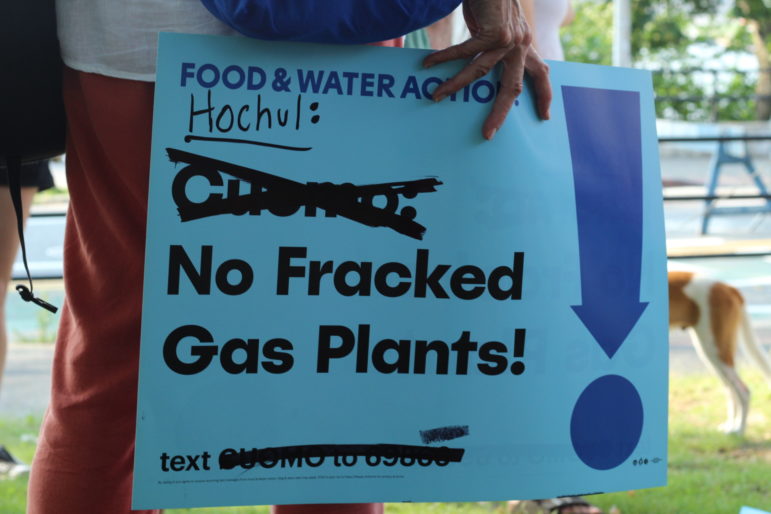

Liz Donovan

A protestor holds a sign at a rally opposing the NRG power plant proposal in Astoria in 2021. The state later denied the plant’s permit application.The group has been pressing the governor to reject utility company National Grid’s application to expand a natural gas processing facility in north Brooklyn, a decision Hochul’s Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) has repeatedly delayed. They were disappointed when the All-Electric Building Act—which would have banned gas hookups in new construction across the state starting in 2024, three years earlier than Hochul’s proposal—wasn’t included in this year’s budget or approved in the most recent legislative session, nor was a bill that would have directed the New York Power Authority phase out fossil fuel power plants by 2030.

And some activists have criticized the governor for net yet signing a bill, approved by lawmakers this past spring, to restrict new fossil-fuel burning cryptomining operators until the state could study their environmental impact (Zeldin has said he would not sign such a bill: “We shouldn’t be picking winners and losers in business,” he said; Hochul’s office said the governor is reviewing the legislation.)

“There’s things that she could be doing that would be huge wins for her, and that would get people really excited to reelect her,” Ziesche said.

But Tighe and other stakeholders said they’re optimistic those policies will come to pass in the months ahead, if Hochul gets another term in office.

“She’s very practical, right? She wants to make sure that we’re not getting ahead of ourselves in a way that’s going to hurt the economy,” Tighe said. “She’s leaning in hard on moving to a clean energy economy, and making sure that we’re doing so in a way that’s thoughtful.”

More Election Reporting:

- Fate of Immigrant New Yorkers at Play in Governor’s Race, Advocates Warn

- Hochul, Zeldin and Housing: A Breakdown

- Buyouts on the Ballot: 10 Years After Sandy, New York Considers New Funding for Voluntary Relocation

This article was written as part of the 2022 NY State Elections Reporting Fellowship of the Center for Community Media at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY.