The candidates in the race for New York governor have vastly different platforms on housing. To start, Gov. Kathy Hochul, a Democrat, has a housing plan. Republican challenger and U.S. Congressman Lee Zeldin does not.

Flickr.com/gageskidmore | Darren McGee/Office of Governor Kathy Hochul

Congressman Lee Zeldin and Gov. Kathy Hochul

Rents have risen to record highs. So has New York City’s homeless shelter census. More than 100,000 public school students were homeless last year, the seventh year in a row that number has reached six digits.

With Election Day approaching, you’d think housing, something that affects every single person in New York, might be the animating issue in the race for governor. You’d be wrong.

The race has been defined by inflation; an uptick in violent crime and incessant bail law demagoguery; real threats to women’s reproductive rights and abortion access; and the far-right attempt to disrupt American democracy embraced by Republican candidate Lee Zeldin, a Long Island congressman who voted not to certify the results of the 2020 presidential election.

But the two candidates also differ when it comes to housing. To start, Gov. Kathy Hochul, a Democrat, has a housing plan. Zeldin does not.

On the campaign trail, Hochul has highlighted her housing policy proposals and her record over the past 15 months as she seeks a full term. She announced a five-year, $25 billion plan to create and preserve 100,000 units of affordable and supportive housing in her State of the State speech earlier this year. More than 22,000 units of housing have been built or preserved across New York State since September 2021, her office said.

Housing experts criticized last year’s budget and state legislative session for lacking solutions to the affordability and homelessness crises, but Hochul and state Homes and Community Renewal Commissioner RuthAnne Visnauskas have pledged to tackle housing issues in the next budget.

“Governor Hochul has made increasing the supply of safe, stable, and affordable housing a cornerstone of her administration—particularly as inflation and other rising costs continue to place a strain on New Yorkers,” Hochul spokesperson Justin Henry said.

Zeldin, the Republican challenger, rarely discusses housing policy. During an interview with the New York Times editorial board last month, he did not answer when asked directly if he has a housing plan. Instead, he has released statements criticizing some proposals, like new tenant protections and challenges to exclusionary zoning, or making vague policy recommendations. That has left housing experts confused about what Zeldin would do to create more affordable housing and tackle homelessness if elected on Nov. 8.

“If you stay quiet and don’t have a plan you can continue to critique your opponent’s stance without giving anyone ammunition,” said Marc Norman, the head of New York University’s Schack Institute of Real Estate. “I don’t like that as a way of having a fully functioning society but I understand it as a political strategy.”

Zeldin’s website has only a handful of housing policy proposals, including ending veteran homelessness and streamlining new development. He gave a cursory response to a question about rising rents and evictions at the only candidate’s debate last month, and his campaign ignored emails with specific policy questions for this article.

New York housing policy experts interviewed for this story struggled to point to Zeldin’s positions on housing issues. Hochul, they said, has at least offered concrete proposals and notched some achievements.

“So far as I can tell Lee Zeldin doesn’t have a housing platform,” said Rafael Cestero, CEO of the Community Preservation Corporation and a former commissioner at the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) under Mayor Mike Bloomberg. “We don’t know what he thinks or whether he even thinks there is a housing crisis.”

So where do the candidates stand on specific housing issues? Here’s a breakdown.

New housing development

“To me, the next governor really needs to tackle the housing supply shortage in the state head on,” Cestero said.

The issue affects the entire state, not just New York City. Cestero pointed to the example of a new Micron chip plant in Syracuse that could create 9,000 new jobs and attract new residents in need of homes to the area. Residents of the Hudson Valley have been priced out by buyers moving north from Brooklyn and Manhattan.

Hochul has pledged to prioritize new housing around transit centers and signed legislation to ease residential conversions of hotels and commercial spaces—though the highly-touted plan has yet to create a single new home. Under Hochul, the state has added $130 million to the Homeless Housing Assistance program, which has gone toward creating 36 supportive housing sites with 1,155 units, her office said.

Adi Talwar

The Paramount Hotel (green roof) on 46th Street in Midtown Manhattan. A year after the state passed a law funding the conversion of hotels to affordable housing, not a single one has happened.

She has proposed increasing density in new New York City residential developments by lifting floor area ratio (FAR) limits, which are currently capped at 12 but are lower in most parts of the city. (FAR refers to the maximum square footage of a building allowed by local zoning rules, based on multiples of the lot size. An FAR of 12 means 12 times the size of the property lot, for example.)

Earlier this year, she also backed a plan to legalize accessory dwelling units (ADUs)—extra apartments in basements, attics or garages that are, in many cases, already being used for housing—in lots zoned for single-unit homes. She backed off the proposal after facing opposition from suburban moderates, like her primary challenger Tom Suozzi. Her fiscal year 2023 capital plan would have directed money to towns and nonprofits to help homeowners bring those extra units up to code.

Zeldin has forcefully opposed the ADU proposal, calling it a “blatant attack on suburban communities [that] will end single family housing as we know it, strip local control away from the New Yorkers who live there, tank the value of their homes, overcrowd their previously quiet streets, and on top of it all, not do anything to solve our affordable housing problem.”

But the exclusionary zoning in the New York City suburbs, and in parts of the five boroughs, was deliberately enacted to prevent Black residents from moving in. The limits continue to restrict home ownership and rental opportunities. Norman, from NYU’s Schack Institute, said allowing additional housing in areas zoned for single-family homes is a small, but powerful tool for addressing the housing shortage.

“It might not have a huge effect on the housing supply, but symbolically it would be important that someone is focused on the crisis,” he said. “I think NIMBYism is one of our last bipartisan issues.”

Zeldin has called for more affordable housing, but he has offered few specifics on what he would actually do to drive more development in New York.

At an event in Harlem, he said the state needs to help New York City “fast track affordable housing construction” and require people who file lawsuits seeking to block rezonings or new development to “post bond.” He repeated that proposal during an interview with the New York Times editorial board.

“Projects need to be expedited and prioritized,” he said. “There’s also way too many lawsuits unnecessarily slowing down development.”

When asked about record rents, evictions and upstate New Yorkers priced out of home ownership during a debate on NY1, Zeldin again said a lengthy approval process forces “individuals and companies that want to invest here” to head to other states.

“We have people at the state level, bureaucrats drawing it out. You can abuse the litigation process to draw this process out,” he said, before pivoting to discuss the need to create more jobs.

Yet job creation has far outpaced new housing development in the city. A 2020 report from the Citizens Budget Commission found that New York City produced less than 0.2 new units of housing for every new job created between 2010 and 2018. That increases competition for housing and leads to higher rents and sale prices, problems fueled by outside investors scooping up properties.

Sarah Watson, interim director of the policy group Citizens Housing & Planning Council (CHPC). said Zeldin’s comments shed little light on what he would actually do to shorten the approval process and streamline affordable housing creation.

“I think Hochul has had a strong few years on housing. Zeldin, we don’t know what a housing plan would look like,” said Sarah Watson, interim director of the policy group Citizens Housing & Planning Council (CHPC). “We’re in a desperate place, not just in the city, everywhere in the state. It’s an absolutely critical issue that needs to be front and center.”

What to do about 421a

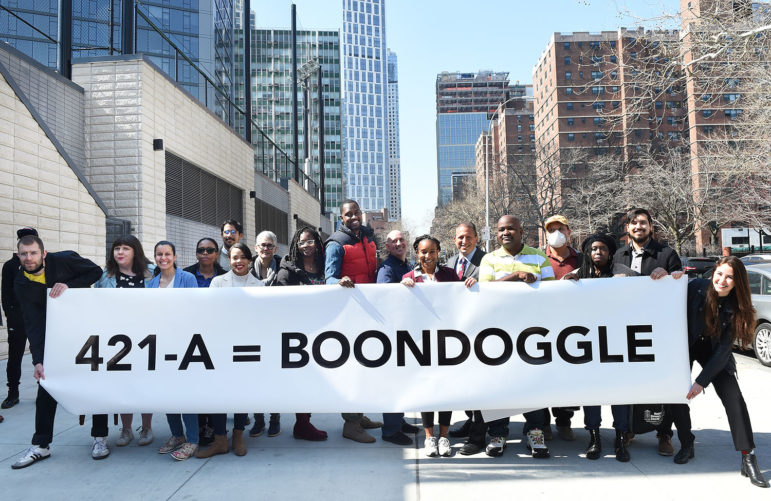

Both candidates say they support reinstating a controversial property tax break for developers and owners that expired at the end of the last legislative session. The 421a program waives most property taxes for developers who erect new residential buildings in New York City in exchange for rent-stabilization protections and some income-restricted units.

Progressive lawmakers and housing advocates say the program is a giveaway to developers with little affordable housing in return, and have called for more targeted tax breaks or deeper affordability rules. The program has cost New York City nearly $1.8 billion in lost tax revenue each year, but most of the income-restricted, or so-called “affordable,” apartments created under 421a have been priced for middle- or higher-income earners.

Susan Watts/Office of New York City Comptroller

Advocates and members of the NYC Comptroller’s office at a rally calling for the end of the 421a replacement last spring.

Supporters of the program, most notably the real estate community, say the incentives are crucial for spurring development since costs mount well before an application is approved and shovels hit the ground.

Zeldin said he supports 421a as it stood before expiring.“I don’t believe that 421a should have expired, and I support for 420a [sic] continuing,” Zeldin told the Times in June.

Hochul last year proposed a modified version of the program called 485w that would lower the income cap and rents on the units deemed affordable. She has pledged to revisit that proposal next session, when the absence of an election could facilitate negotiations on a heated topic.

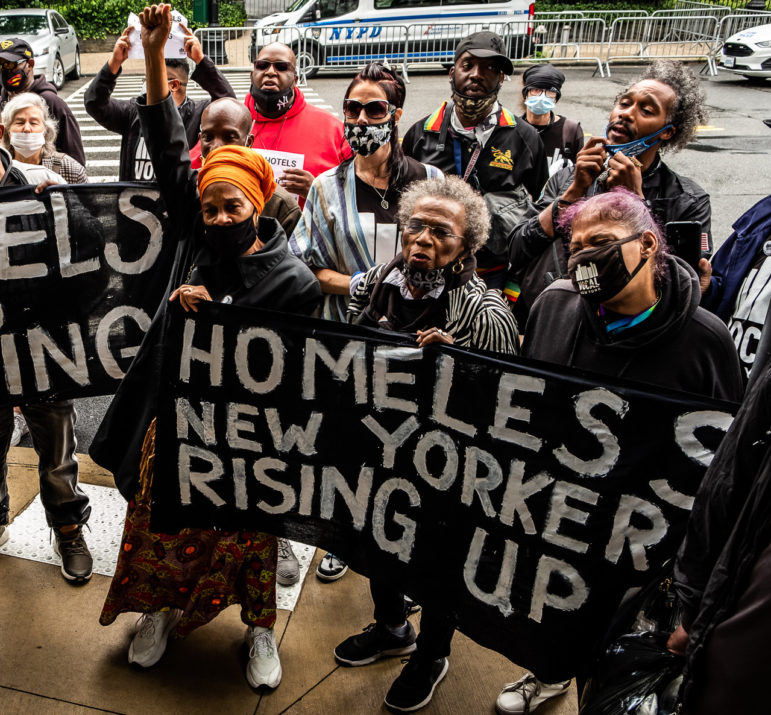

Solving New York’s homelessness crisis

More housing is sorely needed, but years pass before people actually move into newly created apartments. In the meantime, more than 65,000 people are staying in New York City’s Department of Homeless Services shelters, according to City Limits’ daily tracker. Thousands more are in shelters run by other city agencies.

Progressive housing advocates say they have two priorities for the next legislative session: Good Cause Eviction protections (more on those later) and a new Section 8-style rent subsidy, known as the Housing Access Voucher Program (HAVP), that would help people at risk of or experiencing homelessness secure and maintain housing.

HAVP had the support of both chambers of the New York legislature last session, with each adding $250 million to jumpstart the initiative in their budget plans. Real estate interests, including the Real Estate Board of New York and landlord groups, have supported the proposal.

But HAVP died during budget season after facing opposition from administration officials over inflated cost estimates, according to people involved in the negotiations at the time.

“Last year, the governor didn’t support HAVP but I think she got bad information on the program and the future savings,” said Legal Aid housing attorney Ellen Davidson. “It’s an incredibly popular program both with tenants and landlords.”

Would Hochul support the program in 2023? That’s unclear, but one leading housing organizer said she is optimistic given the depth of the current crisis.

“The truth is, the housing crisis is worse than it ever was,” said Housing Justice For All organizer Cea Weaver. “People can’t afford rent, people are being evicted and there’s 100,000 homeless children. We need this now.”

Zeldin’s campaign did not respond to questions about HAVP.

As homelessness worsens, the state has continued to abdicate responsibility for shelters and services in New York City, forcing the city to cover the vast majority of the expense in contrast to years past—an imbalance created by former Gov. Andrew Cuomo. Under Hochul, New York has also made the city draw from a funding pool intended to house immigrants without legal status to cover an increase to state rental assistance vouchers.

Twice, Hocul has joined Mayor Eric Adams to announce a surge in new cops in the subway system to eject homeless riders, though the punitive approach is supposed to come with additional outreach services. Those strategies have not yet led to many people moving into housing.

Zeldin has said he wants to streamline the path from shelter to permanent housing, but has not offered specifics.

During his time in Congress, Zeldin, an Army veteran and a current member of the Army Reserve, did introduce legislation to permanently fund services and cash assistance to poor and homeless veterans. The only homelessness-related policy listed on his website is “Eliminate veteran homelessness” and he discussed the plan at a March presentation before veteran groups.

“You have people who don’t even have a roof over their head,” he said. “Our goal is to have zero homeless veterans in the state of New York. This is absolutely attainable.”

He has also introduced federal legislation to address COVID-19 among homeless New Yorkers and helped steer federal funding to homeless service providers in Eastern Long Island.

Adi Talwar

A rally in June 2021, calling for the city to create more permanent housing for homeless New Yorkers.

Good Cause Eviction protections

Both candidates have explicitly opposed the “Good Cause Eviction” bill that would extend a version of rent stabilization protections to tenants in unregulated apartments, including all buildings with fewer than six units. The legislation would give tenants the right to a lease renewal in most cases, so long as they pay their rent and follow the terms of their lease. The measure would also give tenants a chance to challenge a rent hike above a certain threshold, potentially compelling the landlord to justify the increase in court.

The measure died last year and continues to face furious opposition from landlord groups.

Hochul told the New York Times in June that she opposed Good Cause, referencing landlords’ lost rental income throughout the COVID pandemic after their tenants who could not or did not pay regularly: “I don’t support that,” she said. “I’m very concerned about the small landlords. Many of them have not been paid rent in a very long time.”

The state’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP) has paid out $2.6 billion to 203,446 property owners, according to the state’s latest report, but the program has run out of money on multiple occasions and more than 170,000 applicants have yet to be paid.

At a September panel hosted by the Association of Neighborhood & Housing Development, Visnauskas, the state’s housing commissioner, avoided answering a question about the potential impact of Good Cause protections but said the concept “will remain part of the conversation.”

Zeldin is also staunchly opposed to the measure. In November 2021, he called Good Cause “a push for statewide rent control” backed by the leftwing of the Democratic Party.

“This proposal must be stopped,” he said in a statement at the time. “‘Good Cause Eviction’, just another name for universal rent control, disincentivizes investment in housing and hurts businesses, communities and the very renters who need help.”

Zeldin’s stance on Good Cause and frustrations with the limits of ERAP have attracted property owners to his campaign, The Real Deal reported last month.

Easing Home Ownership

Both candidates have also highlighted the need to foster opportunities for home ownership and have proposed some solutions.

At the debate last month, Zeldin briefly mentioned a proposal to increase homebuyer credits—tax breaks for people who purchase property. “First time homebuyer credits is going to be a very important thing for us to ramp up in this state,” Zeldin said.

During his time in the state Senate, he sponsored legislation to cap property taxes at 2 percent.

Hochul has also focused on homeownership in her housing plan. She backed affordable homeownership in New York City through the creation of community land trusts (CLTs) and other forms of “community-controlled housing” as part of the policy book accompanying her State of the State speech in January.

Under the CLT model, land is owned by nonprofit community-based organizations that rent or sell the housing to low and middle-income residents. Homeowners on CLT land cannot flip their units for a large profit, preventing speculation and keeping the units permanently affordable.

Her proposal to revise 421a also includes a provision to add an “all-affordable homeownership option” for low- and middle-income New Yorkers.

Matthew Dunbar, the chief strategy officer for the New York City chapter of Habitat for Humanity, welcomed that addition to the plan earlier this year, noting that home ownership in New York City is unattainable for the vast majority of residents.

“This is the first time in a long time that a governor’s plan is putting significant weight behind the equity-building part of their housing plan,” Dunbar said. “It would be a huge benefit for the city.”