After nearly 40 years in operation, The Partnership for the Homeless on Monday became the Partnership to End Homelessness. “We very much believe that homelessness is solvable and should be solved, given that it especially hurts women and children of color in our city,” the group’s CEO said of the change.

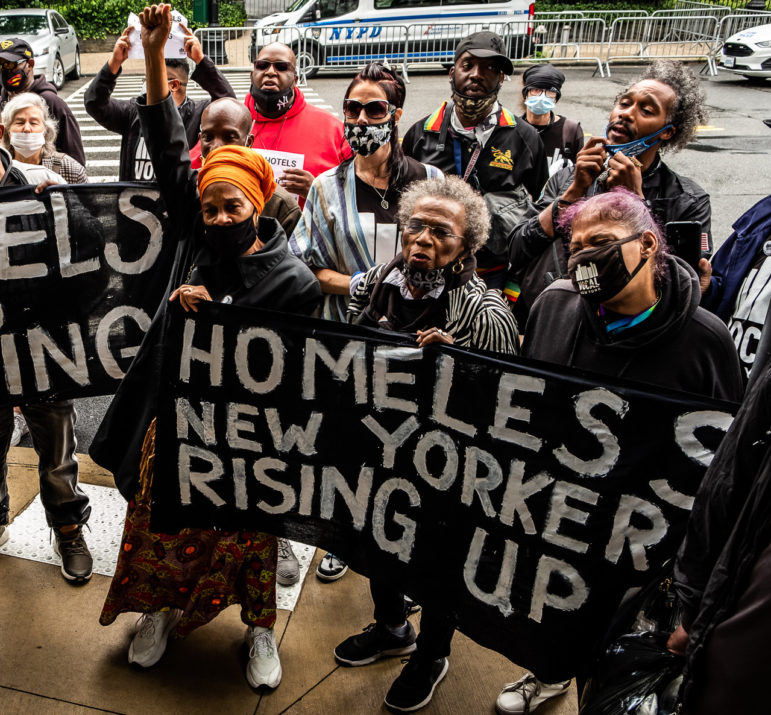

Adi Talwar

A rally in June 2021, calling for the city to create more permanent housing for homeless New Yorkers.Years of rising rents and shrinking housing options have fueled an ongoing crisis of homelessness in New York City, where more than 60,000 people stayed in a municipal shelter in January. The problem’s durability drives a sense of resignation, a notion that homelessness is inherent to modern urban life, says Áine Duggan, a nonprofit administrator.

But that notion is false; homelessness is an economic equation that can be solved with cash, housing and political will, Duggan says.

After nearly 40 years in operation, her organization is rebranding to reflect that framework. The Partnership for the Homeless on Monday became The Partnership to End Homelessness.

“The name better reflects the vision of our organization,” said Duggan, the Partnership’s CEO. “We very much believe that homelessness is solvable and should be solved, given that it especially hurts women and children of color in our city.”

Families with children, nearly all of them Black or Latino, make up the bulk of the city’s Department of Homeless Services (DHS) shelter population, though the number of single adults entering shelters has surged to near-record highs in recent years.

Founded in 1983, the Partnership prioritizes homelessness prevention by providing cash grants to families and individuals at risk of eviction, while mediating disputes or problems between renters and landlords. The organization also connects people to counseling, health and education programs and served roughly 10,000 New Yorkers last year, according to its annual report.

“Our new name also seeks to humanize and unveil who experiences homelessness, highlighting that homelessness is an economic experience, not an identity marker,” Duggan said.

The grants can be especially key for households that missed out on the state’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program, which ran out of funds last year.

A surge in evictions could undo the steady progress in reducing homelessness that New York City has made in recent years. The number of families in DHS shelters shrank with pandemic-related eviction protections in effect, continuing a pre-COVID trend (though advocates point out the city has also been denying shelter to the majority of families who apply).

With the end of eviction protections has come an increase in new housing court cases, which tenant groups and policymakers fear will result in a rise in a spike in evictions and homelessness. Landlords have filed more than 34,500 eviction cases across New York State so far this year, with the five boroughs accounting for nearly 20,000 of those, according to an online tracker maintained by the state court system.

Those numbers are on pace to far exceed the amount of filings last year and roughly equal the total from 2020, when the state first established eviction protections. The difference now, however, is that the protections in effect in 2020 and 2021 stopped all but about a few hundred legal evictions in New York City.

“We’re hearing more urgency, more fear in our client conversations,” Duggan said. “This will be with us for quite a long period.”

New York lawmakers are likely to add more money to the exhausted rent relief fund in the state’s upcoming budget, though the amount will likely pale in comparison to the need. More than 430,000 New York City households remain behind on their rent, putting them at risk of eviction, according to data compiled by the policy group National Equity Atlas. The federal government has provided just a sliver of the $1.6 billion that Gov. Kathy Hochul has requested to replenish the fund.

The Partnership’s rebranding reflects a broader attempt to frame the issue of homelessness as an economic and systems problem that can be solved by prioritizing affordable housing development, streamlining moves into vacant apartments and changing policy to unlock more homes across the city.

In an introduction to his organization’s annual report earlier this month, Coalition for the Homeless Executive Director Dave Giffen sought to center the debate around the lack of available housing.

The “fundamental reason for mass homelessness,” Giffen wrote, is “the lack of affordable housing options for enormous swaths of our population. Painting mass homelessness as an individual failure rather than a systemic inequity has resulted in billions of dollars being spent on emergency responses, while the underlying problem remains unaddressed. And so, the human and financial costs continue to mount.”

New York City has taken significant steps to prevent people from becoming homeless, offering cash grants to tenants in arrears, increasing the value of housing vouchers to keep pace with market rates and providing a lawyer to the lowest-income renters in Housing Court. Those methods have slowed the rate of entry into shelter and decreased the DHS shelter population by about 15,000 people since a 2016 peak.

Still, helping people currently in shelter move into permanent homes has proven a challenge, with administrative hurdles combining with landlord discrimination and a tightening rental market to keep people out of housing.

But all of those problems are fixable, said State Sen. Brian Kavanagh, sponsor of a bill to create a new state housing subsidy, in an interview last month.

“We used to talk about ending homelessness. Now we talk about managing it,” Kavanagh said. “We as a society ought to have the resources so that no one lacks housing because of an inability to pay.”