Federal and state eligibility rules disqualify those who file with Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers, or ITINs—a common practice among immigrant workers. Experts estimate that there are around 107,610 children in ITIN-filing households across New York State.

Jarrett Murphy

Lea la versión en español aquí.

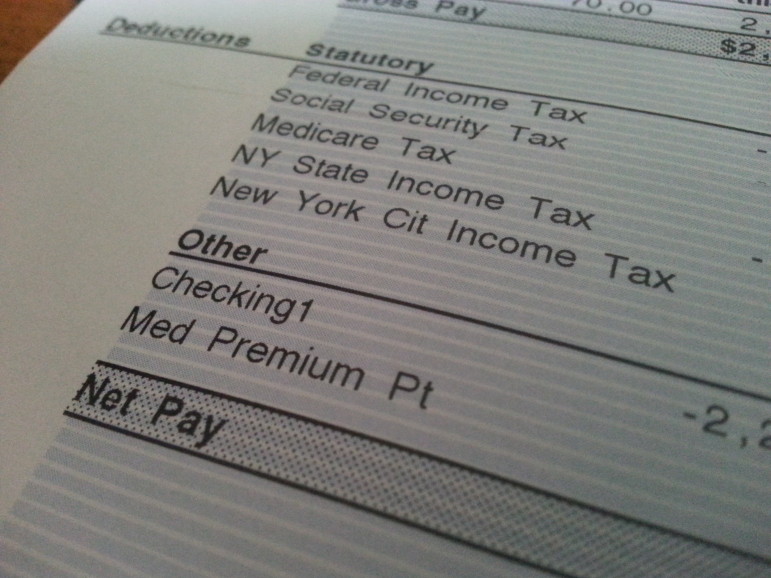

Another school year has just begun, and one of the strategies the government has taken to curb child poverty has been through tax credits, specifically two programs: the Child Tax Credit (CTC), which provides monthly payments; and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), a refundable tax credit for low- to moderate-income working individuals and couples—particularly those with children—that is claimed when filing a tax return.

One of the requirements to qualify for the EITC is to have a valid Social Security number (SSN), be a U.S. citizen or resident alien; for mixed-status families filing jointly, one of the two filers is required to be a U.S. citizen or resident alien during the tax year. This step disqualifies many families who file with Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers, or ITINs—a common practice among immigrant workers who lack a SSN. Experts estimate that there are around 107,610 children in ITIN-filing households across New York State.

During the pandemic, 10 states have enacted or reformulated their EITC to reach more workers in need, and states such as California and Colorado expanded the application to specifically include ITIN filers, according to Samantha Waxman, a policy analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP).

New York has not expanded its state EITC, and legislation that would allow ITIN filers to qualify for the state version of the credit has failed to pass in either the Senate or Assembly during the two most recent legislative sessions, despite the fact that an estimated thousands of these ITIN-filing families are raising U.S.-born children. The Vera Institute found that 87 percent of the 2 million children in New York City with at least one immigrant parent are citizens themselves.

“One may be a practical reason,” that the state hasn’t made the change, says Dorothy (Dede) Hill, policy director at the Schuyler Center for Analysis and Advocacy. New York State’s EITC is a percentage of the federal EITC and follows the same federal eligibility rules, which exclude undocumented families and others who don’t qualify for a Social Security Number, and whose only option is to pay taxes with an ITIN number.

From an administrative standpoint, Hill says, it would be a bit more difficult for the state to expand the EITC to ITIN filers since it would not conform to federal eligibility rules. But that doesn’t mean it can’t be done, Hill clarifies, since “NY did ‘decouple’ its Empire State Child Credit from the federal Child Tax Credit a few years ago. As a result, our state child tax credit is eligible to ITIN filers even though the federal CTC is not available to those filers.”

There was an effort to include an expansion of the CTC in the 2021-2022 New York State budget (Senate bill S.5866 and Assembly 3146-A) that would have provided up to $1,000 for families with children under age 4, and $500 for children between 4 and 17. Neither of those bills came up for a vote in the most recent legislative session in Albany.

“This year the priority was the Excluded Workers Fund,” says State Assemblyman Andrew Hevesi, who sponsored the CTC expansion bill.

New York took a huge step toward closing the loopholes created by the federal exclusion of ITIN filers from unemployment insurance and stimulus payments with the creation of the Excluded Workers Fund (EWF), explains David Kallick Director of the Fiscal Policy Institute’s Immigration Research Initiative.

However, the EWF was a mitigation program and does not focus on reducing child poverty. At a press conference on Sept. 15, Roberto Suro and Hannah Findling of the University of Southern California concluded that it would be nearly impossible to achieve historic reductions in child poverty among immigrant families if the bureaucratic impediments of the U.S. tax system are not resolved.

To increase the incomes of low-wage earners, 29 states, plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, have enacted their own version of the federal EITC, recognizing it as an effective tool for advancing equity and reducing child poverty, especially for people of color, women, and immigrants, who are over-represented in low-wage jobs.

One of the reasons these types of programs are so effective at reducing poverty is because they provide “immediate relief while also incentivizing work and earnings,” said the authors in a recent article. New York enacted its own EITC in 1994, directly tying eligibility and credit levels to the federal EITC, and a study of 90 low- and middle-income neighborhoods links it to individual-level health improvements across both the city and state.

Hevesi, chair of the Committee on Children and Families in the Assembly, says he is pushing for an expansion of the CTC but not the EITC, saying there are not enough resources for both.

A bicameral set of bills (S537 and A2533) would have included ITIN fillers for the state EITC but didn’t come up for a vote during the last two legislative sessions. Similar legislation was introduced in the City Council in 2020, which called for the state legislature to make both the state and city versions of the credit eligible to ITIN holders, but it likewise failed to pass.

The spokesperson from Assemblymember Patricia Fahy, who sponsored the state bill, told City Limits there are plans to reintroduce the legislation in Albany next session.

In the meantime, the children of New Yorkers who file using the ITIN can only access one of the two major tax programs in place to combat child poverty. Including ITIN filing households in New York State would have a direct impact on children’s lives, experts say.

According to figures from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, there are 3,515,080 children in ITIN filing households in the United States. Of these, the majority are U.S.-born children, Kallick adds.

“The federal tax code is supposed to be blind to immigration status and tax equality is about ensuring that everyone regardless of status who pays into the system has the same access to tax credits,” said Suro.

City Limits also asked several of the members of both the Assembly and State Senate Children and Family committees. Only a representative for Sen. Roxanne Persaud in the Senate responded, saying that the senator “does not have a comment at this time but will raise these questions with the Committee Chair.”