The State Assembly and Senate passed a bill Monday that would extend the former moratorium on most evictions—protections that lapsed May 1—through the end of August. A separate state initiative to distribute federal relief funds to property owners whose tenants owe back-rent is not expected to be up and running until the end of the month.

Sadef Ali Kully

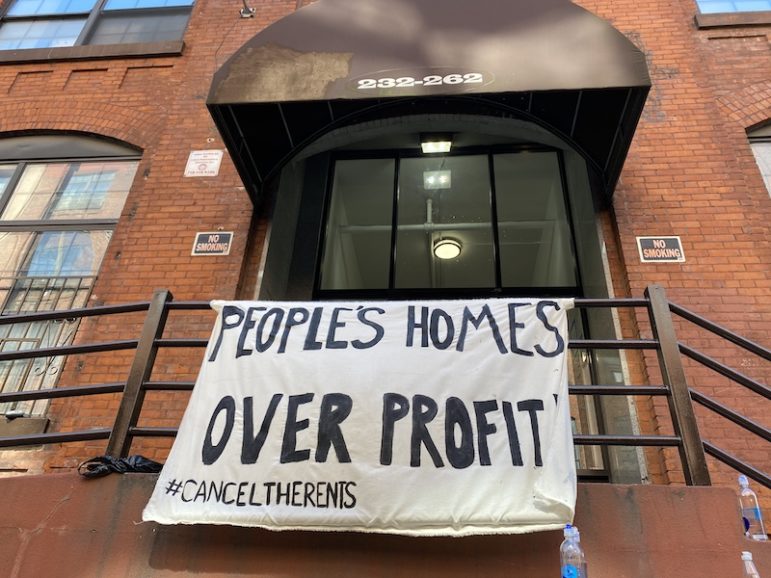

A sign protesting rent collections in Brooklyn during the height of the Coronavirus epidemic.Updated 9 a.m. on May 5, 2021

Lawmakers approved a measure Monday to extend the state’s eviction moratorium—which lapsed May 1—to the end of August, citing the ongoing COVID-19 crisis and its impact on New Yorkers’ ability to pay rent.

The bill, which was later signed into law by Gov. Andrew Cuomo on Tuesday, extends the COVID-19 Emergency Eviction and Foreclosure Prevention Act of 2020, which was passed in December, for an additional four months. It offers protections against eviction for tenants who’ve lost income, are facing financial challenges or are unable to move because of the pandemic, as long as they file a hardship declaration form attesting to those challenges with their landlord or in court. The bill offers similar protections for small business commercial tenants against eviction, as well as for small property owners against foreclosure and tax lien sales, all of whom can also file a hardship declaration form under the moratorium.

“What we’re doing today is protecting all New Yorkers and their need for housing stability, not just residential tenants,” said State Sen. Brian Kavanagh, who sponsored the extension bill in the Senate.

The state’s previous eviction moratorium expired on May 1, though Kavanagh says his bill would apply retroactively once signed into law. The legislation was approved by both the Senate and Assembly on Monday despite push-back from some Republican lawmakers who worry that extending the moratorium will allow the state’s rent debt to continue to accumulate, potentially beyond the amount of money available in COVID-19 rent relief.

The recently approved state budget allocated $2.35 billion in federal relief funds for the COVID-19 Emergency Rental Assistance Program, which would allow eligible households to apply for up to 12 months of rental and utility arrears assistance, as well as three prospective months of rent. The program will be administered by the Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance but has yet to open to applicants, and isn’t expected to until the end of May, lawmakers said. Earlier attempts by the state to distribute federal relief funds to pay tenants’ back-rent were slow to get off the ground, with advocates saying prior eligibility requirements were initially too restrictive; a second application period, which expanded those requirements, still only distributed a small portion of the relief funds available to tenants.

“If we keep kicking the can down the road and excusing rent from being paid, it’s highly likely that the federal monies that are given to us will not be enough to provide relief to all landlords,” Sen. Daphne Jordan, who represents a district upstate, testified Monday.

Kavanagh said that while it’s hard to gauge exactly how much rent New York’s tenants owe across the state from the pandemic, he cited one estimate which put the amount in January at somewhere between $1.4 and $2.2 billion. In addition to the $2.35 billion being allocated for rent relief, there is an additional $100 million in state money and another $600 million being set aside for homeowner relief funds—likely enough, he says, to cover the collective debt owed.

Some Republican lawmakers also argued against the bill because they feel it makes it too easy for tenants to declare a pandemic-related hardship, allowing certain “bad actors” to avoid paying rent even if they’re able to and adding to small landlords’ struggles.

“This law allows certain bad actors, as minuscule as they may be, to continue their operations and take advantage of the system,” said Assemblymember Michael Tannousis, who represents parts of south Brooklyn and Staten Island.

The moratorium bill does create an exception to allow for the eviction of “tenants who persistently and unreasonably engage in behavior that substantially infringes on the use and enjoyment of other tenants or occupants or causes a substantial safety hazard to others.”

“Tenants in my area are not freeloaders,” countered Assemblymember Deborah Glick, who represents the west side of lower Manhattan, testified Monday before voting in favor of the extension. “They have been extraordinarily anxious that they have not been able to pay their bills.”

She and and other Democrats say the alternative to not extending the moratorium would be to put hundreds of thousands of tenants across the state at risk for homelessness at a time when the impacts of the pandemic are still being felt. One 2020 reported estimated that New York could see between 800,000 to 1.23 million households unable to pay rent and at risk for eviction at the start of this year. The state’s unemployment rate was 8.5 percent in March, down substantially from the height of the pandemic but still significantly higher from before the COVID-19 crisis, when it was 3.9 percent.

“While we can make a pronouncement that the subways are open 24 hours and that the city is open, the reality is, a lot of businesses are not bringing all of their people back and the economic activity that comes from street traffic is not necessarily going to magically, with the flip of a switch, disappear,” Glick said. “We cannot have people still in the middle of a pandemic forced into homelessness or forced into housing court.”