The rates have fallen since their May highs, but the gap with Whites remains wide.

This story was originally published in Spanish. Esta historia se publicó originalmente en español. Lea la versión en español.

The most recent national unemployment snapshot shows that the pandemic has been devastating for Latinos and Blacks: higher infection rates, higher death rates and higher unemployment rates from the start of the pandemic until July.

Nationally, the Latino unemployment rate has followed the downward national trend in June and July —the last two months on record. While May reached one of the most critical points in the unemployment rate for Latinos (17.6 percent), June and July show a slow recovery: 14.5 percent and 12.9 percent, respectively.

However, unemployment rates by race/ethnicity show a gap that hasn’t decreased correspondingly. In May, for example, unemployment for White people in the United States stood at 12.4 percent, a difference of 5.2 points compared to Latinos in the same month. In July, the unemployment rate for Whites was 9.2 percent, a 3.7-point difference from Latinos in the same month.

For Black workers, unemployment in recent months has been even higher. In July, for instance, it was 14.6 percent, almost two points above the rate for Latinos and a difference of 5.4 points above the rate for Whites. In June, Blacks also reported higher unemployment rates: 15.4 percent versus 14.5 percent among Latinos and 10.1 percent among Whites, meaning a 5.3 point-difference from Whites.

According to the latest figures from the New York State Department of Labor, the Bronx, the county with the largest number of Latinos, had the highest unemployment rate in the entire state in July: 24.9 percent, slightly higher than the rate in June (24.7 percent). Among what has been seen locally in Queens, more unemployed people have become street vendors and more people are looking for food in pantries.

According to Valerie Wilson, director of the race, ethnicity and economy program at the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), several factors fuel these disparities. On the one hand, there were unequal pre-pandemic conditions: Since the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics began tracking unemployment by race in the early 1970s, the rate has been highest for Blacks, with Latinos close behind. This is one reason why Latinos and Blacks had higher poverty rates and lower incomes pre-pandemic, which made them more vulnerable to many aspects of the crisis. On the other, COVID-19 has had a disparate impact: Job losses disproportionately affected industries where Latinos and Blacks worked.

What makes Latino workers more vulnerable and disproportionately impacted than others in today’s labor market is “the occupational segregation of Latino workers into more vulnerable jobs, as well as on underlying economic factors”, suggests EPI´s report.

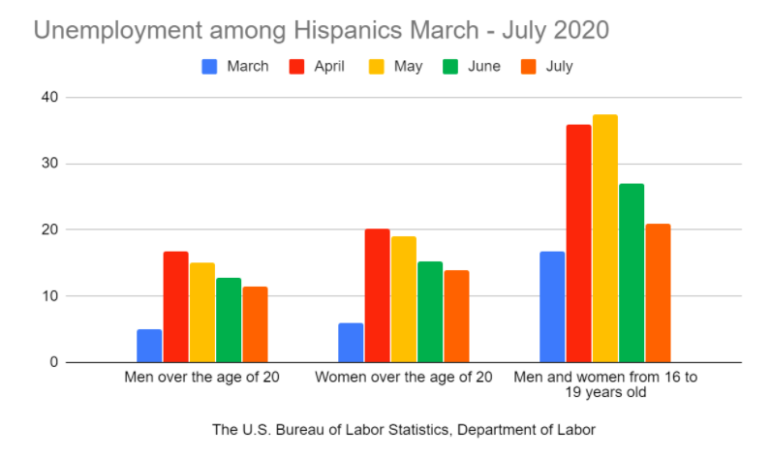

The recent unemployment among Latinos has unevenly impacted younger working Latinos and Blacks (16-19 years old) and Latino and Black women. Why? Women are more likely to work in jobs that have been particularly susceptible to job loss during the pandemic.

May’s unemployment rate for young Black workers reached a 34.9-percent peak recovering slowly from there to July, 22.5 percent. Young Latino workers saw a higher loss in May, 37.4 percent, though recovered a bit faster than young black workers by July, to a 21 percent unemployment rate.

As the report highlights, the true unemployment rate could be higher among Latinos because the category of “White” is defined as “white, of any ethnicity,” and might be including some Latino workers.

“If the data were mutually exclusive, that is, if the White unemployment rates were reported for White non-Latinx workers only, then the White unemployment rates would be even lower, and the unemployment rate gaps between White and Latinx workers would be even larger,” reads the report.

Another statistical quirk obscuring the impact of the crisis is that many who are without jobs are not considered “unemployed.”

“To better understand the economic impact,” says Wilson, who is also one of the report’s co-authors, “two measures should be considered: unemployment rates and employment-to-population ratios (EPOP).”

EPOP also confirms the differences between Latinos, Blacks and Whites in the United States. Between February and April, for example, more than one in five (21 percent) Latino workers lost their jobs, and, more than one in six Black workers lost their jobs, while for white workers it was 15 percent.

“The beginnings of a recovery in May and June translated into significant job gains for Latinx

and white workers alike, but Latinx workers still face a far larger job deficit from February

to June than white workers, 9.1 percentage points versus 5.9 percentage points,” reads the report.

EPOP also confirms gender differences among Latino and Black workers. “Nearly one in four (23,9 percent) Latinx women in the workforce lost their jobs, compared with 18.1 percent of Latinx men, over those two months,” reads the report.

EPOP rates for black women dropped 11.0 percentage points and 10.0 for black men. “Put another way, 18.8 percent of black women workers lost their jobs between February and April,” reads a June report.

The last characteristic of unemployment among Latinos is the place of birth. Before the start of the pandemic, there was not much difference between the unemployment rates of Latino foreign-born and U.S.-born Latinos: 18.6 percent and 18.4 percent, respectively.

But then the pandemic hit and changed the picture. In June, the unemployment rate for U.S.-born Latinos was 15.3 percent, while for foreign-born Latinos it was lower, 13.5 percent, according to the Pew Research Center.