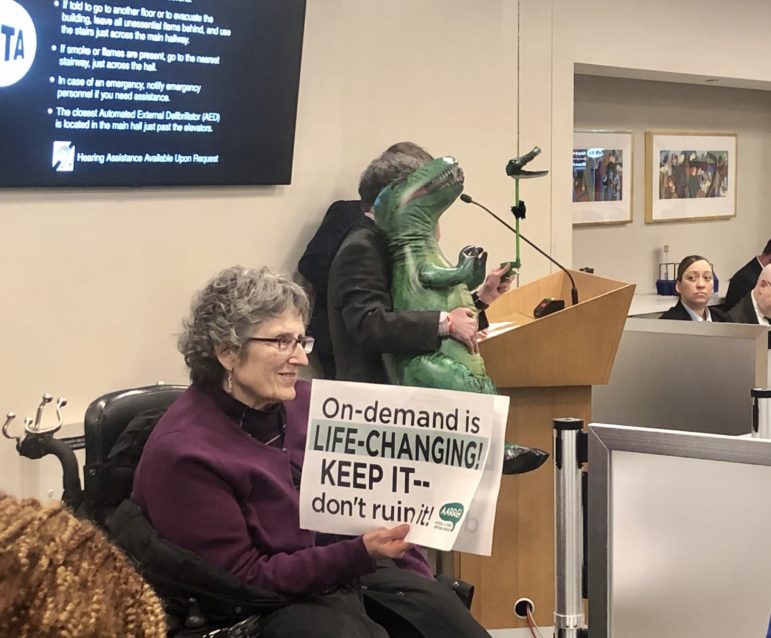

City Limits/Jeanmarie Evelly

Jean Ryan of Disabled in Action holds a sign protesting planned changes to a popular Access-a-Ride program at an MTA board meeting. (City Limits/Jeanmarie Evelly)Access-a-Ride users testified at an MTA board meeting Thursday against the agency’s plan to alter a popular pilot program that allows participants to schedule green and yellow taxi rides on-demand, limiting the number of monthly trips those users are able to take under the initiative.

The “On-Demand E-Hail” pilot initially launched in 2017, and allowed some users of Access-a-Ride—an MTA-run car service for commuters with disabilities that prevent them from taking public transit—to electronically book taxi rides as needed, for $2.75 a trip. The pilot proved immensely popular, with users hailing it as life-changing because it allows them to schedule rides immediately, as opposed to having to book a day in advance, as is required under traditional Access-a-Ride. The pilot program serves 1,200 users, up from 200 when it first launched.

But sometime this month, the MTA plans to make changes to the on-demand service: While it will double its reach to include 2,400 Access-a-Ride users, it will also limit their number of rides to 16 a month, and cap the per-ride subsidy at $15. While the MTA did not immediately respond to a query about how much the pilot program cost last year, it cost the agency $8 million in 2018. The MTA’s entire paratransit budget in 2019 was $614 million, MTA Bus President Craig Cipriano testified during a City Council hearing in December, what he said was a 29 percent increase since 2017.

“This shows no signs of slowing down,” Cipriano said at the hearing, where he also appealed for the city to increase its contribution to the MTA’s Access-a-Ride budget. The city currently covers either a third of the MTA’s paratransit net expenses or 20 percent more than it paid the year prior, whichever is less, he said. “We believe that a 50 percent share of the cost is fair.”

The MTA has not given a specific date for when the changes to the on-demand e-hail program will go into effect, but an MTA spokesman told City Limits that the new usage caps will kick in before the end of March, and that users in the program will be notified ahead of time.

When that happens, the pilot will expand to include another 1,200 users, something MTA Chairman Pat Foye told reporters Thursday will help the agency get a more accurate sense of how the on-demand option would be utilized by Access-a-Ride customers, since its current participants were chosen at least partly on a voluntary basis.

“We doubted the reliability of the data from the first group of 1,200, which to some extent was self-selected,” Foye said. “This [new 1,200 users] will be a group that is picked randomly and is more representative.”

But those who’ve come to rely on the on-demand option say the new rules will render the popular pilot useless, in spite of its growth.

“They can say they’re expanding it left and right, but it’s not an expansion. They’re rationing it, and they’re ultimately gutting and killing the program,” says Eman Rimawi, a campaign organizer with New York Lawyers for the Public Interest.

She says the $15 subsidy cap will barely cover the cost of even short taxi trips on congestion-plagued city streets, leaving pilot participants with hefty bills to cover the difference. She says a recent on-demand ride from her office on 43rd Street and 6th Avenue to her pharmacy on 39th Street and 3rd Avenue cost $15.30.

“You can only go so far,” Rimawi says. Once she goes over her allotted number of 16 on-demand trips under the new policy, she’ll be forced to use traditional Access-a-Ride service for the rest of her rides, which requires users to book at least a day in advance. Those rides are also shared with other Access-a-Ride users, meaning trips are often lengthy, with drivers taking circuitous and indirect routes to drop off and pick up other passengers, sometimes for hours at a time.

“Now I feel that I’m just going to be even later for things, or just not show up for things,” Rimawi says.

Users and accessibility advocates argue that it’s unfair to limit rides under the program, and are calling for the MTA to offer an on-demand booking option to all of Access-a-Ride’s 160,000 users, saying the requirement that rides be scheduled one to two days ahead of time makes the service impractical for meeting actual real-life demands.

“What are you going to do tomorrow? How long will your meetings last? Well, if you’re on Access-a-Ride you have to book it today: when you want to be there, and when you’re going to leave,” Jean Ryan, of the advocacy group Disabled in Action, testified at the MTA’s board meeting Thursday, where she and other Access-a-Ride users protested the new policy with dinosaur-themed posters and an inflatable Tyrannosaurus Rex—a tongue-in-cheek display meant to urge the MTA to modernize the service.

“We need on-demand without restrictions. Otherwise we’re just going to be hanging around waiting for a ride all the time, or missing meetings and leaving before they’re done, things like that,” Ryan said. “It really is not really possible to live an active life like that.”

Advocacy groups are also pushing for state lawmakers to act on a bill, sponsored by State Sen. Leroy Comrie, that would require the MTA to continue the on-demand e-hail program through spring of 2022 and expand it to another 1,200 users without placing any usage restrictions on participants. The bill would also require the MTA to produce a report on costs and how the program is used, with the goal of expanding it further.

Justin Wood, an organizer with New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, says they estimate extending the program as the bill dictates would cost no more than $16 million, what he says would be a “very modest cost” for the city and state in the long-run, and would provide additional data on the pilot program that could be used to expand it.

“It’s just not too much to ask to provide a life-changing service to New Yorkers with disabilities,” he says.

17 thoughts on “MTA Moves Forward with Changes to Access-a-Ride Pilot, Despite Protests from Users”

I have no problem booking a day before before because I go to doctor appts for the most part.

What I have a problem with is getting a lift or ramp. I was approved for a para-transit on my initial interview because I cannot climb stairs. My right leg is inflexible. When I make my reservation I t tell the booking agent I need a para-transit with a lift or ramp and always get a black or whatever car that I have to climb into. The driver has to help me and he has to lift my right leg into the car. That means he touches my body. The driver is embarrassed. I am embarrassed. And it is painful for me to endure having me right calf touched.

I complained, but was told I am approved for a para-transit.

So, I avoid appts or try to book two appts on one day or juggle.

AAR does not listen to complaints, so I do not complain.

some people with disabilities would like to go to work

Exactly, I work every day, and I need reliable transportation to and from work. And sometimes, I actually like to go out with friends after work, or check on my sick parents when they are unexpectedly taken to the emergency room, I would like to see my parent, while they are sick. Like everyone else.

Excellent description of current Access-A-Ride issues. It appears the current program omitted planning for employed users. At 89, I’m retired. So I agree that having to guess when my event will end is only conjecture, but that’s the least of it. Reserving rides a day or two ahead is okay. It’s when the drivers don’t seem to be able to find my building that is irritating. However, I’ve adjusted to using the “messages” icon on my phone to try to make the meet-up happen promptly. Often trying to get information by phone is impossible: reps don’t realize I can be calling from a dark, windy, noisy street with heavy traffic and they mumble by rote into the phone. Absolutely exasperating.

I don’t use the service like other New Yorkers but I’m interested in going back to school I’m intent on making the service my way to get around. It’s not fair that one who has financial troubles or might be stuck in class has the option of 15 trips or booking 2 days in advance !

I degree on the cap on E- haul program. I live in a very hi populated mall area just to get from my home to Queens Boulevard is $15.

There was a trip I had taken a traditional Access A Ride van I got In the van at 4:30 PM they put me on a Brooklyn route even though I was going to Queens drop everyone else off which was a total of four people.I did not reach my home until 730. They pick up a total of 4 different people in Brooklyn. Drop all for people off in different locations in Brooklyn. Then proceeded to drop me off at my home. This is one of the reasons why I am so disgusted with the traditional access a ride van I have been picked up in.

I was happy to hear when you were going to open the email program again.But now I am very upset that I’m hearing that you were going to put this On the hill so meaning if I join the hill I’m still going to be limited on how I could take my rides and how many rides I take.

No one in the MTA board plan their life a day ahead so why should the disabilities community have to plan their life a day ahead? People with disabilities have enough barriers in their life already! We shouldn’t have to be stress out about how we going to get around in the city.

MTA need to stop the rationing and provide full access to the disabilities community!

I completely agree at times I feel stuck at home because I have to make a decision a day or two before just to get a ride I want to be able to book a trip the same day I feel like I need to go outside without being told You should of called the day before

I’ve never experienced such ungrateful riders of AAR I have two elder aunt’s & father-in-law with the service, & their complaint is traveling with passengers who have no serious time demand trips going to the casino, clubs, parties, BBQs etc. Seams to be the travelers with the most complaint’s which they do understand the importance of traveling as normal to wherever they would like to with no prejudice, I myself will feel someway for those who travel on a more time demand destination dialysis, hospital, school work etc, we all know $2.75 is nowhere close to covering a trip which means it’s on taxpayers I would like to know if some passengers know the cost of a trip? Example to travel to Bronx to S.I, S.I to the Bronx that’s easily close to $100 if not more I tell my elder family all the time wow that’s great door to door service. I often see non AAR travelers struggling to get to their destination bus to train train to bus, which I’m sure they’ll be grateful for such service. Above statement reads $15 won’t cover my trip what I say to that is now put yourself in a person who’s probably only making $15 an HR & have to shell out paying for a metrocard & have to take the train & the bus & still have to walk a distance, let’s be humble ppl let’s be humble patience is key, Safe travels to all

some people with disabilities would like to go to work

All this is going to do is put us back onto the regular horrible Access a Ride system and vans, it takes away our ability to have a basic quality of life that people that can use Mass Transit have. They have effectively accomplished what they started out to do and get rid of this life changing service. The MTA’s motto is to Screw the Disabled. I use the pilot taxi on demand service locally but rides are never less than $15 and most of my doctors are in New Hyde Park or Manhattan. You can’t get out of Brooklyn for less than $15 so now I’m going to be forced once again into 2-3 hour rides on top of late rides, long waiting times, and no show drivers, etc. I’ll have to stress at doctor appointments fearing I’ll miss a ride home and the stress will once again be unbearable. The NYC MTA STINKS – ABSOLUTELY NO COMPASSION FOR THE DISABLED. I AM TOTALLY DESTROYED BY THIS. BEGGING OUR LOCAL POLITICIANS TO STEP IN AND STOP THEM FROM DOING THIS.

I agree.

My husband has pancreatic cancer and we go into Manhattan from Staten Island for his Chemo treatment. Every time I call them I ask for a car, they tell me they can’t guarantee a car. I think they need to invest in some smaller cars, for people traveling a little further than their own boro. Leave the vans for wheelchairs or when they have two or three customers going in and out of the same boro..

Have AAR 4 long time! However, drivers + clients can be HORRIBLE! Lots drivers speed over bumps + shocks on the bus “HORRIBLE”!! IF U HAVE ANY CHRONIC PAIN RE:BACK ETC IT GETS WORSE. NO CONSIDERATION FOR SENIORS WHO HAVE 2 GO 2 BATHROOM LIKE ME! I HAVE URINARY INCONTINENCE HAVE 2 GO 2 BATH- ROOM VERY OFTEN! CALLED ELIGIBILITY YELLED AT” IT’S A SHARED RIDE(3HRS FROM 5-8PM

Driver asked if service dog BITES told him he insulted me then tells me not to speak in SPANISH which is my native language.Scarlotte my service dog knows spanish + I speak 2 her in my NATIVE LANGUAGE!!! LAST RIDE MY WALKER WAS BROKEN. MUSLIMS DON’T LIKE DOGS believe SALIVA of dogs UNSANITARY if DOG’S mouth TOUCHES clothing can’t say their prayers! To me we’re all children of God when w Scarlotte start crying + screaming saying Scarlotte go 2 bite them they LIE!!!!! Called AAR TOLD ME TO GET OFF IN MIDDLE OF BKLYN/QUEENS EXPRESSWAY. THERE R PEOPLE ALLERGIC 2 DOGS/AFRAID BUT AAR NO CARE! 1 TIME MAN COMES ON W $100.00 BILL. DRIVERS SUPPOSED 2 CALL DISPATCHER. ASKED ME IS OK I SAID I WOULDN’T DO REPORTED HIM THERE R RUDE CLIENTS 1 PLAY

MUSIC BLASTING ASKED PLEASE LOWER NO CARE DRIVER DID(0). I COULD WRITE A BOOK RE THINGS THAT HAPPEN BUT I I HAVE BETTER THINGS 2 DO I’m 69yrs old use rollator Walker w service dog named Scarlotte.l have chronic pain 4 yrs!!

I FEEL EVEN IF WE COMPLAIN IT’S DOESN’T MATTER WHAT HAPPENS TO US REALLY DOESN’T MATTER MTA WILL DO WHAT EVER THEY WHAT JUST HAVING MEETINGS TO SAY YOU HAD IT, NOTHING EVER COMES OUT OF MTA ALREADY KNOWS WHAT THERE GONNA DO BEFORE THE MEETING

I was one of the lucky 1,200 access o ride users to be put in the on-demand taxi program. then I realized I wasn’t lucky. There was a plan. They picked the biggest complainers. The heaviest users. the activists from the disabled community and put us in the program. They specifically asked for our feedback about how it worked. now they’re complaining that it cost too much. They asked us to use it!

Yeah, we’ll use it a lot, it’s life-changing! Regular access a ride made it impossible for me to have a job. Adding an hour and a half to my ride and either direction is unacceptable now I can travel when I need to travel and not be taken on a tour of New York City.

This on demand Access-A-Ride program has allowed disabled people to become productive members of New York City. Caping it at at 16 rides a month and only paying for the first $15 is just sabotage. Every ride I take saves the MTA about two-thirds of what it would be paying one of them blue and white vans to take me on a serrepetase route to work.!

I am so hurt by them trying to stop the e hail program. With this program I’m able to get up at the last moment take a cab and be where I need to be. Last year almost to this date I got a call from my cousin who said my grandmother is about to pass away and the doctors called me and said if I want to see her one last time to get there immediately. All I had to do was call a cab through a app on my phone and I was there in no time to see my auntie before she passed away. Now it’s my father, he’s in the hospital and I usually try to go see him each and every day. I don’t really have a set time when I go see him because he’s in a hospital where I can see him 24 hours. I usually go to pick up my mother and then we go to the hospital to see my father. Is very important that my mother gets to see my father everyday. It makes me feel good to know that I can help go see him each and every day. There’s been plenty of times when he’s had to be rushed to the emergency room and all I have to do is call the cab and I’m there for my daddy but if you take the service from me I won’t be able to do that. I will have to wait 2 days before I can see my father. If he goes in the hospital after 5 I can’t call Access-A-Ride to tell them I need the ride until the next day, if I have to wait till the next day to call them to tell them I need their service I won’t get to see my father until the day after. Please don’t change this service. I can’t afford the new change I truly truly need it just as I’m sure so many others do. This service has been such a blessing to me. I can’t believe it will end soon. Please don’t say oh we’re not cutting the service off we’re just changing it. You know just as well as I do that if you start charging us that much money to take the curb it will be just like shutting the service down because we cannot afford the change. Also you know this very well. I feel that you don’t want to just shut it down because then that’ll make you look like the bad guy but if you change it to something you know there’s no way we can afford. We will stop taking it, then you’re going to say oh we had the service for them they didn’t take advantage of it so we’re going to shut the whole thing down. I’m so hurt behind this news.

I live about 31+ to 45 miles from my doctors which means I do not now have transportation. This is not acceptable. What good is my medical coverage when I can’t get to my doctors and have complicated medical problems. This cuts me off from my doctors. This is not a time to look for new doctors. I tried locally and had test and due to test ended up in ICU which never happened in NYC. I have 3 different eye doctors in NYC and was blind is this a time to cut me off from my doctors. I tried in my local hospital and it was not successful so I ended up in NYC. I need to see my doctors and I am also a senior with many medical problems and it is also Cov. Virus now. Does anyone think I traveled about 2+ hours with Accessaride for no reason and have to wait hours for return trip to make sure I can get a ride home. Anyway, I can’t see my doctors and need needle in my eye or I can become totally blind.