City Council

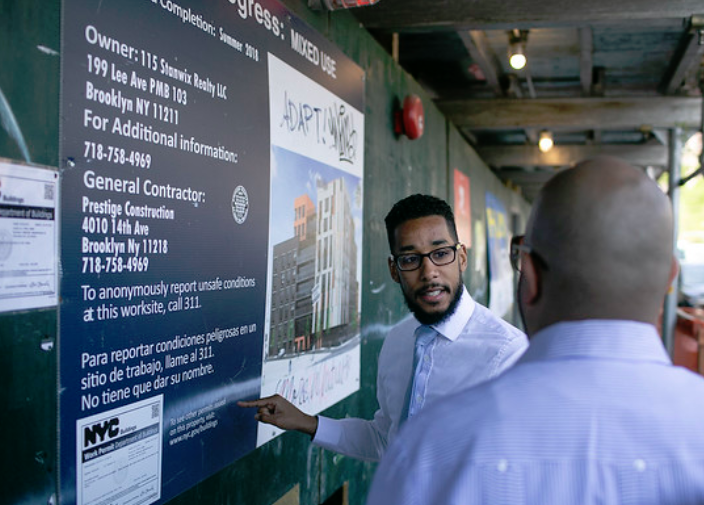

Councilmember Antonio Reynoso gives fellow members a tour of the area of Bushwick slated for a rezoning.

The discussion about development, housing, rezoning and gentrification in New York City is sometimes painted as a tug of war between those who embrace change and those who resist it, hopelessly.

In Bushwick, it’s clear that picture is inaccurate. Yes, change is inevitable, as the shiny new restaurants popping up further and further east along Knickerbocker Avenue, the clubs and venues in former industrial spaces and the snazzy new apartment buildings poking up amid the familiar brown of six-story brick buildings attest.

But Bushwick is proof that there are different types of change, and that policy choices can determine which kind you get. The neighborhood saw the bad kind in the 1970s and 1980s, and community advocates and politicians worked to achieve different kinds of change in the intervening years. These battles demonstrated that change can be directed, harnessed. The debate in Bushwick as a rezoning looms isn’t an argument about change versus status quo, but rather, a debate about what kind of future to aim for.

Councilmember Antonio Reynoso, who joined this week’s Max & Murphy Show, says there is an element of preservation in the rezoning he’s trying to achieve. “The community’s population is still mostly Latino, which means that the displacement hasn’t happened full stop,” he said. “A big reason why we want to do this rezoning is so that we can curb speculation. A lot of people think that what these communities are trying to do is stay the same. That’s not necessarily what they want. I think they would invite new residents if it means they still keep their apartments.”

Along with Council colleague Rafael Espinal, Reynoso launched in 2014 the Bushwick Community Plan, which brought together stakeholders to produce a vision for how to channel change in the neighborhood through a pro-active rezoning. Not everyone got on board; some believe any rezoning, however well intentioned or designed, raises displacement risks. But the group did manage to produce a comprehensive vision.

Now the de Blasio administration has produced its own blueprint for Bushwick, and while it incorporates much of the Community Plan, it departs from it on key points: the amount of market-rate housing to permit, and the preservation of industrial space.

The latter issue—whether to tolerate the conversion of industrial space into residential—has implications for the whole city, which has seen manufacturing space dwindle. Reynosos sees a very local impact.

Get the best of City Limits news in your inbox.

Select any of our free weekly newsletters and stay informed on the latest policy-focused, independent news.

“Recent statistics show that the majority of the people that work in the manufacturing district in Williamsburg and Bushwick walk or bike to work. So, while we don’t have the exact addresses and know whether or not they’re from the community, we know they’re either walking distance or biking distance, which makes them what we consider our community folks,” he said. “That’s the majority of workers, that’s more than 50 percent, so we know that manufacturing is valuable and important to a lot of people. 17,000 jobs, not just in manufacturing, across those areas. We want to protect those jobs, and the problem we have is that residential development encroaches on industrial development, and it’s a domino effect. Once they build one building they just keep coming in and coming in. People know you can get a lot more per square foot from a residential building than you can from an industrial building.”

City Limits, which did an in-depth report on Bushwick a decade ago, is embedding its reporting staff in the neighborhood for the next four week to see what changes have occurred and which ones might be coming.

Hear our conversation with Reynoso below, or listen to the full show, which includes a pre-Independence Day discussion of the state of civil liberties in New York City.

Brooklyn Councilmember Antonio Reynoso

Max & Murphy: Civil Liberties in 2019; Bushwick’s Past and Future

with reporting by Cyan Hunte