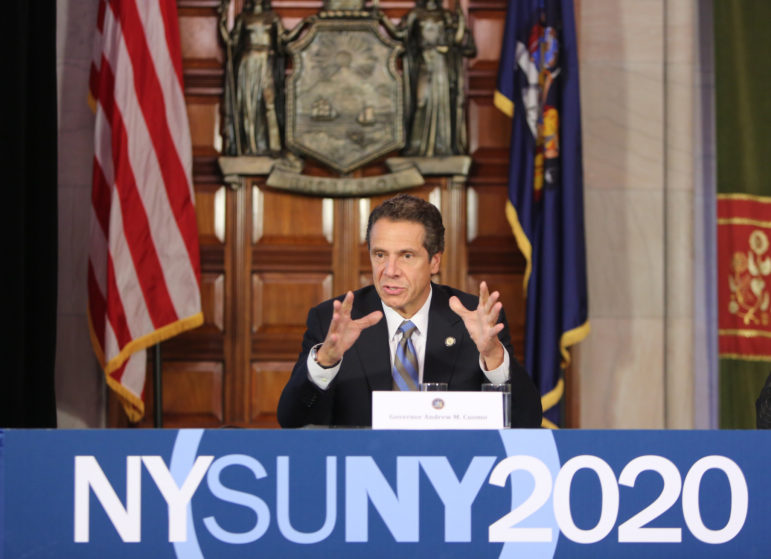

Office of the Govenror

Gov. Cuomo's Excelsior scholarship program served 20,086 students last school year. But a recent report found only 3 percent of public college students are able to take advantage of the program.

As the September 13 Democratic primary approaches, City Limits is comparing the two gubernatorial candidates on the issues. Below is a brief examination of their positions on housing policy. Other articles in this series cover criminal justice, housing and transit.

Cynthia Nixon likes to say she’s a proud public school graduate and parent. She was a longtime advocate for public schools and has said that education is the reason she entered the race. But how do her policy platforms stand up against Cuomo’s gubernatorial record?

While Cuomo didn’t make education the centerpiece of his 2018 State of the State address, he rolled out the Excelsior Scholarship the year before and the latest state budget passed under his leadership raised education funding, as well as moved to address hunger in the student population.

Both have had a lot to say about education. Here’s where the two candidates stand in several key categories:

School Aid

Nixon and her allies have lambasted the governor for what they characterize as inadequately funding education. She blames Cuomo for continuing budget cuts imposed in 2010 by former Governor David Paterson and continuing to not fully fund foundation aid, a formula born out a lawsuit that increased funding primarily for high-need, low-income school districts.

In his 2018 State of the State address, Cuomo continued to discuss funding inequities and in the the FY 2019 budget proposed $26.4 billion in school aid, an increase of $769 million from last year. Almost half was to go toward a $338 million or 2% increase in Foundation Aid, bringing the total of such aid to $17.5 billion. After negotiations, education aid was ultimately increased by approximately $1 billion.

Still some, including Nixon, saw it as a case of too little too late. They also opposed a new requirement that school districts submit school-level allocation plans to state officials, arguing that it distracts from the real problem of inadequate funding.

This cause is near and dear to Nixon as an advocate and candidate. She became an advocate when she saw the negative effects of budget cuts at her child’s New York City public school.

If elected, she says her first budget would include a plan to fully fund foundation aid, phased in over three years, that would increase the state’s annual investment in K-12 education by $4.2 billion.

David Bloomfield, an education professor at Brooklyn College and CUNY Graduate Center, says that the $4.2 billion increase is unlikely because it’s not only a large amount of money, but it amounts to a redistribution that could hurt property rich suburban districts upstate and in Long Island by raising their taxes. Democrats and Republicans in those districts who want to hold onto their seats are likely to avoid voting for the funding, he says.

Higher education

Gov. Cuomo announced The Excelsior Scholarship in 2017. Under it, people making up to $125,000 per year qualify to attend tuition-free at CUNY and SUNY two- and four-year colleges. It’s what’s called a “last dollar” program, covering tuition left only after other grants and aid have been used, and the funds cannot be used for expenses like room and board. It requires 30 credits per academic year and requires alumni to stay and work in the state after graduation. According to a recent report, 20,086 students statewide received an award from the Excelsior program in the 2017-2018 school year.

Nixon has her own College for All New York program, which she says will provide free tuition to an additional 170,000 SUNY and CUNY students at an annual cost of $600 million: It would cap the income for eligibility at $80,000 and is a “first-dollar” program would allow students to reserve other grants to pay for expenses. It would be open to DREAMers and would would require 24 credits per academic year but not any requirements for students to stay or work within the state after graduation.

A recent report by Center for an Urban Future concludes that only 3 percent of public college students are able to take advantage of Excelsior, which had a 70 percent rejection rate, and that students in New York City are especially neglected.

Nixon’s program lacks some of the restrictions that cause those problems, Bloomfield says, and he thinks it casts a wide enough net that the legislature would be able to pass

it.

“It plays across the [geographic and demographic] board statewide in a way that the K-12 proposal of nixon’s doesn’t,” he says.

Jeanne Zaino, professor of political science at Iona College, thinks both Nixon’s school aid and higher education proposals are a long shot because of the cost to taxpayers, and the political will it would take to impose that on voters. Still, she agrees with Bloomfield that the College for All proposal is more politically palatable because of who benefits.

Charter schools

Cuomo has historically supported charter schools. The most recent state budget increased per pupil funding for such schools, and as part of a deal that quickly followed the renewal of mayoral control of city schools in 2017, legislators agreed to a workaround of the charter cap by allowing the reuse of “zombie” charters and for the city, as well as providing MetroCards to charter school students when school starts before busing, among other provisions.

Charter school proponents have also supported Cuomo, though some detractors claim he’s backed away from the movement. Nixon supports fully funded public schools and has decried spending on charter schools. She tweeted in April that “Too many corporate Democrats like Andrew Cuomo are taking charter-school hedge-fund money. We have to stop diverting education funding into privately run charter schools, and put the focus back where it should be: on strengthening our public schools and keeping them public.”

Testing

Cuomo has pushed for an Annual Professional Performance Review program in which tests loom large, something teachers lobbied against but was nevertheless reflected in the state’s budget. It takes power over evaluation plans from districts and teachers’ unions and gives it to the state education department.

Nixon would repeal the APPR and return teacher evaluations to local control. Along with the Board of Regents, she would review all mandatory state and federal testing and its consequences with the goal of reducing standardized testing in the state.

During his 2010 campaign, Cuomo advocated for Common Core standards, but later backed away from that position. In 2017, Next Generation English Language Arts and Mathematics Learning Standards were introduced after Cuomo convened a task force amid the opt-out movement that recommended a Common Core overhaul.

Cuomo has gotten behind legislation that would prevent the state from using state exam results to evaluate teachers and to instead use “alternative assessments.” He also accepted a task force’s recommendation for a moratorium on using the test results to rate teachers through the 2018-2019 school year.

“I think Cuomo is burdened by his past effort in terms of Common Core and test-based teacher accountability,” Bloomfield says.

One thought on “Cuomo vs. Nixon on Education Policy: Testing, Charters and Money Loom Large”

Pingback: New York’s Democratic Primary is a Showdown for Charter School Politics – OtrasVocesenEducacion.org