Office of the Mayor

Officers at an NYPD ceremony in 2010.

How many movies have featured a version of this scene? A confrontation between the tough, hard-charging detective and the pencil-pushing police supervisor who’s getting pressure from downtown to ease up on the politically connected big-shot whom our hero suspects is as dirty as yesterday’s handkerchief. Things get heated. Harsh words are spoken. It ends with the captain demanding that the good guy hand in his badge and gun (or his/her “shield” and “piece” in some tellings).

It probably doesn’t work that way in real life. But cops do get stripped of their gun from time to time—”placed on modified duty” is how it is described in the press. Just in the past few weeks, it’s happened to several of the figures caught up in the FBI probe of alleged NYPD corruption and to the CPR instructor who was blamed for the poor first-aid training that may have contributed to the death of Akai Gurley after Officer Peter Liang shot him. Officers who figure in questionable arrests or use-of-force incidents are often placed on modified duty.

What’s unclear from press accounts is whether this administrative step takes place in cases that don’t make the newspapers, and what happens to the cops who are so assigned. Do they eventually shift back to regular duty? Or do they languish on the “rubber-gun squad” for years?

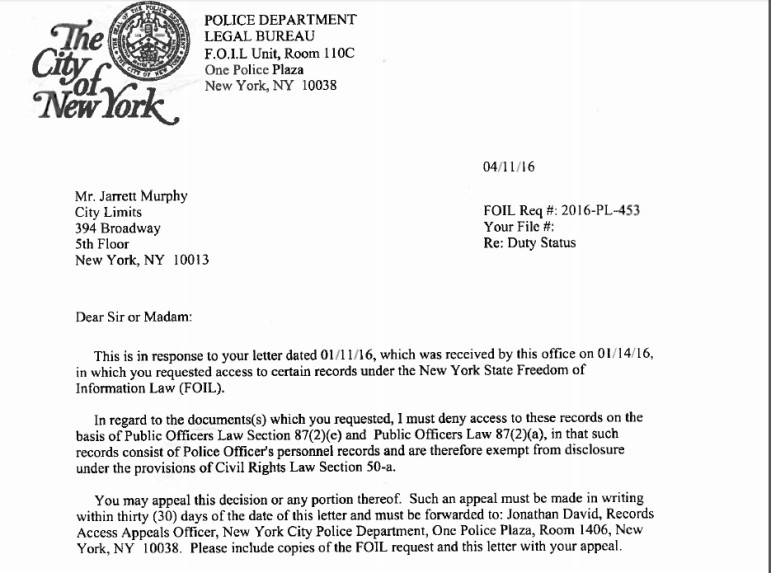

To find out, City Limits requested info on the officers who were on modified duty or suspended from duty at a point in time early this year.

This week, however, we learned that we won’t be learning the answer to our question. An NYPD FOIL officer turned us down, citing a familiar piece of state law.

Section 87(2)(e) is an old frenemy of City Limits’: We encountered it five years ago when we wanted to see if the Bloomberg administration would be as enthusiastic about turning over the evaluation reports on NYPD officers as it had been to hand out teachers’ evaluation reports to the press. We learned that cops, firefighters, correction officers and emergency medical workers are specially protected from scrutiny under the state’s otherwise pretty robust freedom of information laws.

The New York Committee on Open Government has pressed to change that law. The effort has yet to succeed. But transparency advocates will keep pushing to revise it—at least until they take away our badge and gun (by which I mean our printer toner and booklet of stamps).