- Dear Santa,

I am the mother of three (3) beautiful childs of the 5, 13 years old and one of eight month (8)… The most important thing I want is to give my childrens happiness sadly enough I can’t buy the basic thing in life. I would be so grateful if Santa Claus would send things. Luis is 13, pants size 16-18 sneakers 9 coat sweaters = 16-18. Magdalena is 5 years old Pants = 6, sneakers = 13, coat and sweathers = 6 Emiliano is (8) month old pants 18-24 m sneakers = 4-5 Coat and Sweathers = 18-24 m. Thank you, Santa Claus for making dream be come true.

Three years ago on Christmas Eve, the New York Times ran a story about adults who encourage young kids’ faith in a roly-poly fellow who delivers toys through chimneys–even as grown-ups feel sheepish about promulgating the fib. A psychologist from Yale was quoted, reassuring parents that tots abandon the fantasy in a few years. Nevertheless, he warned, anyone “who still believes in Santa after that probably needs professional help.”

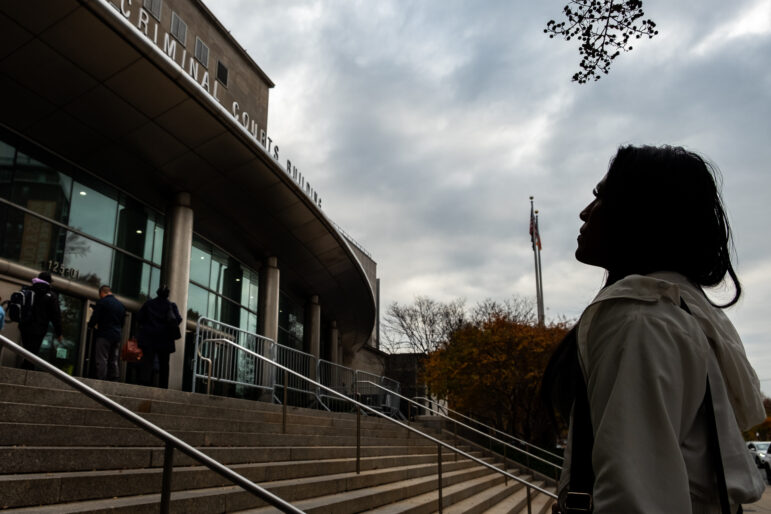

The Yale man obviously hadn’t considered Operation Santa Claus, an elaborate New York City ritual in which thousands upon thousands of locals write to the bearded legend each year and earnestly address him in the second person, though most writers are themselves old enough to have whiskers, or fertile wombs.

Consumers of populist media like the Daily News, The Post and Fox Channel 5 News are bombarded each December with stories about Operation Santa Claus, so they know it’s a seasonal charity drive run from the colossal James A. Farley General Post Office, on 33rd Street and 8th Avenue by the Macy’s flagship store. The same locales were featured in the film Miracle on 34th Street, and for the past several years, reporters have been urging New Yorkers to nurture Kris Kringle’s spirit by visiting the main post office between Thanksgiving and Christmas.

There, in a room decorated with cardboard Donners and Blixens, you can dip your hands into cardboard boxes overflowing with handwritten missives to Santa, penned by the indigent of the Bronx, Brooklyn, Washington Heights, Harlem and the Lower East Side. You can spread the letters on school cafeteria–style tables and pore over them for hours. Soon, according to one Operation Santa promoter, a letter will make you weep by “singing” to you.

Whether unbearably tragic or poignantly winsome, the song always includes a return address, and a request for a dizzying array of items: things like sweaters, X-Boxes, Play-Station 2s, Timberland boots, Game Boy Megaman Extreme 2’s, Yu-gi-oh trading cards, Bratz dolls, Phat Farm down coats, even computers and tuition for private high school. After wiping your eyes and shrugging off the big-ticket items, you take the letter to H&M or Toys R Us or Old Navy and buy what you can. Then you giftwrap your purchases and send them parcel post to the return address. Or, if you enjoy dressing like an elf and are not too fearful of places like Bed-Stuy and Fordham Road, you deliver in person on Christmas Day.

Last December, the tables were crowded for weeks with people waiting to be sung to, and the cardboard boxes spilled over with an estimated 260,000 letters–20 times as many as when the count was first publicized, nearly two decades ago. As always, the media last year implied that most letters were written by very young, low-income New York kids of all the darker-skinned ethnicities. In fact, as postal workers will reluctantly admit if you ask them point blank, many come from Latino teenagers–and even more are from Latina moms, like the one whose letter opens this article.

Writers like her are far past the age when people in cozy circumstances deem it normal to correspond with a nursery school myth. But like everyone else during the Christmas season, the poor want and want and want. In addition, they need and need the things they need all year: food, clothes, entertainment, education, a sense that someone among the unseen powers that be knows they exist–and cares. “Some years around Christmas time, I feel sad and lonely and need something to cheer me up,” says Judi Cabral. A quiet, round-faced 13-year-old, she lives with a big sister, a little brother and a mother whose husband left and who tries to survive by decorating cakes in the family’s down-at-the-heels apartment in Inwood. In past years after Judi has written letters to the post office, “people have brought me toys, sweaters and Barbies.” She shrugs while speculating that “maybe there’s a Santa somewhere.”

But the city’s middle and monied classes also seem needy. If the Topsy growth of Operation Santa Claus is any indication, more and more require contact these days with their socioeconomic inferiors, even if only once a year through the mail, and even if they carefully omit from the package their own name and address.

It should not surprise that these mutual needs play out so grandly in the Big Apple. Historians say the generous, gift-giving Santa Claus we know today was invented in Manhattan, expressly to help the poor and not-poor coexist with fewer tensions. Even today, that ambition may be St. Nick’s greatest legacy.

_______

Sharon Glassman is one of the not-poor. Petite and chatty, with red, Amy Irvingesque hair, she pours her heart and professional energy into Operation Santa Claus each year, though she’s not a postal worker. Glassman’s a performance artist who appears at corporate Christmas parties, where she delivers a promotional monologue about the program that’s based on her life story.

It starts with a witty description of growing up suburban and Jewish in the 1970s, in a barely observant family that not only lit the menorah in December but also exchanged Christmas presents and sang carols. As a teenager, Glassman wanted to feel Jesus in the holiday–something spiritual–which was missing even from Jewish practice in her home. She tried to “boyfriend” her way to holiness by cadging invitations to the houses and churches of her Christian beaux on December 24 and 25. She still didn’t feel inspired. She joined a Unitarian church. She spent a month at an ashram. Meanwhile, as a single, childless, thirty-something woman in New York, she was turning into a shopaholic. She wasted money on two lipsticks of virtually the same shade because one might look better in sunlight. She imagined that cashmere garments were whispering to her from store windows.

Then she found Operation Santa Claus.

In Love Santa, her recently published book about her experience, Glassman writes that one of the first letters she pulled from the boxes melted her with its direct request to Santa Claus for a modest gift.

“I walk around all day in these meticulous casual ensembles from SoHo and I’m lucky if somebody on the street says: ‘Nice red chenille sweater, baby!’… And now this little kid was offering me love…in exchange for a plastic toy castle in the mail.”

Glassman went shopping, with a few things on her mind. One was the sense that she’d finally connected with her spirituality by recalling something she learned in religious school as a child. It was the Jewish ritual of tsedakah, or charitable giving, in which efforts are made to insure that the receiver never learns the name of the person making the donation. The post office encourages donors to send gifts through the mail while identifying themselves simply as “Santa.” Glassman liked the tsedakahness of it all. She liked the selflessness of spending for someone besides herself. And she loved fantasizing that the kids she was shopping for were her own children. Chatting with salespeople, she would pretend to be a harried but loving mom.

By the time Glassman started her benefit monologue for Operation Santa Claus, in the late 1990s, she was calling herself “Tsedakah Santa” and, more frequently, “Undercover Mother.” She had campaign-style buttons made with a cartoon image of a trenchcoated woman, a la Natasha in Rocky and Bullwinkle. She started distributing the buttons at employee Christmas parties given by corporations like Nickelodeon. She covered tables at these gatherings with hundreds of letters supplied by the post office. The idea was for partygoers to pick one or two, then become “Undercover Mothers” themselves. Glassman is still doing the parties, and she’s pleased at how the letters move young New York professionals like her to perform acts of charity for the poor.

Her favorite indigent writers are those who express gratitude unreservedly and in advance. Often their thankfulness comes not at the start of the letter but at the end. Glassman recalls that one of the first missives that “sang” to her suffered from a ho-hum beginning. “Dear Santa,” it said. “I will be happy if you bring me just this castle for Christmas. But if you bring me a different toy, that will be OK, too. I will leave your cookies in the same place as last year.”

“I could resist that,” remarks Glassman in her book.

But when she got to “PS: I love you, Santa,” she couldn’t not go shopping. “There was no way,” she writes, “to give up on somebody this accepting.”

_______

And that’s the whole point of a ritual like Operation Santa Claus, suggests University of Massachusetts historian Stephen Nissenbaum. In return for taking from more affluent New Yorkers during the holidays, the lower classes offer people like Glassman acceptance–even good will.

“It’s like wassailing through the mails!” Nissenbaum chuckles gleefully.

To get the joke, you have to know something about his book The Battle for Christmas–a meticulous analysis of Santa Claus as a New York City invention. For centuries Christmas had been a bacchanal, a carnival, when peasants and servants–particularly young men–wandered around in inebriated gangs in late December. As they staggered about, they “wassailed.”

Today, dictionaries define wassailing as an early English custom that involved boisterous drinking during the Christmas season and toasting to someone’s health. This is not the whole story. Often, wassailing songs included “trick-or-treat”–style lyrics that threatened local poobahs with harm if they did not serve the wassailers their very best food and liquor. “We’ve come to claim our right,” goes one such song. “And if you don’t open up your door, We will lay you flat on the floor.” Indeed, wassailers would bang on the doors of mansions and even break in. Lords and ladies were expected to welcome this misbehavior and to personally serve the ragged revelers high-quality viands and alcohol. When that happened, the songs praised the rich. “God send our mistress a good Christmas pie…. With my wassailing bowl I drink to thee.”

According to anthropologists, wassailing was a “social inversion” ritual: a seasonal event when a group of people in power switch roles with the powerless. At first glance, writes Nissenbaum, it can seem egalitarian, even revolutionary, to see the rich wait on the poor and the poor eat like the rich. In reality, he points out, such role-switching helps perpetuate the status quo. It lets the poor blow off steam, even as it allows the rich to feel like good, caring people. Social inversion turns the world upside down for a few days in order to keep it aright the rest of the year.

But sometimes, changing economic and social conditions destabilize the ritual. When that happens, all hell can break loose–or at least it feels like it might. This, writes Nissenbaum, is what happened in early 19th-century New York City. People like Clement Clarke Moore, owner of a large tract of land now known as Chelsea, worried then about roving bands of Christmas drinkers. Not only did they bang on the doors of mansions and barge in, they also filled the streets with besotted aggression. More ominously, they were young, male and poor; and if they were not visibly resentful of the rich, the rich still stewed in their own imaginings. A specter was haunting Manhattan: the specter of the mob and the riot.

So Moore and other powerful men of the city–better known as Knickerbockers–invented a new rite designed to keep the riffraff at home during Christmas by redefining how goods should be distributed during the holiday. Heretofore, rich adults had given to poor adults. Now, grown-ups of all classes were to give to their own children–and not in the streets, but by their own hearths.

But how to persuade people to do something novel for Christmas, when the holiday and its traditions are supposed to be ancient and unchanging? Moore came up with the solution: Santa Claus.

He started by publicizing a poem he claimed to have written: “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” which everyone still knows today (“T’was the night before Christmas, and all through the house…”). St. Nicholas was a 4th-century saint who was honored on December 6 in Holland. But the Dutch St. Nicholas was skinny and grim-faced, and he was as likely to give a bad child a birch-rod beating as a good child a gift. To retrofit him for 19th-century New York, Moore moved St. Nicholas to Christmas Eve, plumped him up, provided a sleigh and reindeer, and dropped his noir side. Within a few decades, St. Nick had become Santa, and Christmas was recast as a holiday mainly for kids–one that required lots of shopping in the city’s emerging plethora of stores.

To be sure, adults celebrating the new, Santa-ized Christmas also began with exchanging presents with their grown-up friends and relatives. And haves still gave to have-nots. But now, the favorite impoverished beneficiaries were children, and the goods they received were called charity. Unlike luxury goods that the rich had once handed to wassailers and now gave to their own children, charity consisted of necessities, such as basic clothing and food.

By the mid-19th century, a Victorian image had developed of the individual deemed worthy of charity. The ideal recipient was a version of Dickens’ Tiny Tim: a patient and selfless young child who displayed profound gratitude when receiving a donation, and whose appreciation bridged the gap between rich and poor.

By the 1890s, lavish and bizarrely voyeuristic events were being organized so affluent New Yorkers could observe children getting charity. On Christmas day during the first year of that decade, lunch was served to 1,800 poor boys at multi-story Lyric Hall, on Sixth Avenue and 42nd Street. Every floor was filled with well-heeled adults watching the hungry youngsters eat. Next year, the wealthy were invited to Madison Square Garden to watch 10,000 needy boys and girls pluck gifts that hung from the ceiling by ropes.

_______

Then there was the post office.

“Children have been sending letters to the North Pole at least since the 1870s,” says historian Nissenbaum. Traditionally, they were written by the very young, or by mothers of as-yet illiterate preschoolers, acting as scribes. Typical missives greeted Santa, assured him the writer had been good all year, and ended with a wish-list of gifts and a promise to leave refreshments for the reindeer. Some writers mentioned being poor and unable to afford presents unless Santa brought them. But in post office jargon, every letter was a “dead letter,” destined for destruction after the holidays.

It wasn’t long before the wealthy got a yen to read them.

In 1914, a New Yorker named John Duvall Gluck started the Santa Claus Association, whose goal was to boost belief in Santa by answering letters sent to the North Pole by poor kids. Several local charities encouraged the children they served to write letters, then passed them to the organization, which answered with gifts. In addition, the Santa Claus Association took poor boys’ and girls’ letters from the main post office. In 1928, however, the group was investigated for fraud, and the New York City postmaster stopped sending it letters.

The following year, New York City clerks in the postal service’s Money Order Division picked up the slack by culling letters from poor kids and passing the hat to send some of them presents. Soon, the public was being encouraged to assist by sending money. Then, in 1962, the post office decided to let people walk in off the street and choose their own letters. Operation Santa Claus was born.

It started as a low-key affair. Then came the 1980s. “I went to the post office and got my first letter after I heard Johnny Carson reading some on TV,” remembers Richie Aron, a mail carrier in Manhattan’s Murray Hill district who today is an Operation Santa Claus stalwart. Like Aron, many longtime donors say they first learned of the project while watching The Tonight Show 20 years ago. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that Carson began publicizing Operation Santa Claus then. After all, Ronald Reagan was slashing public spending on anti-poverty programs, a policy later extended by the first President Bush as he urged Americans to downsize government and help the poor through “thousand points of light” acts of charity. Such acts were predicated on the idea that one ordinary individual could directly help another, without a passel of social entitlement policies, bureaucrats and social workers interfering. The new aid was up close and personal.

Meanwhile, things were also changing at the post office. In 1984, the first year the local papers paid attention to such things, Operation Santa Claus reported receiving 13,000 letters during the Christmas season. Subsequently, the increase was dizzying. Eighteen thousand in 1989. One hundred seventy-five thousand in 1995. The number peaked in 2000, when 280,000 letters arrived. The next year, the post–September 11 anthrax scare made people leery of strange mail, and only 210,000 letters were received. But last year, the tally had climbed back to 260,000. This Christmas, Operation Santa Claus officials say they will not be surprised if almost a third of a million letters pour in.

_______

If this year is like earlier ones, most letters will be from the poorest zip codes in New York City. Which means that if you hang out in these neighborhoods, a high percentage of the moms and kids you meet will be writers to Santa. For some reason, this is particularly true in heavily Latino areas. There, a tradition seems to have developed in which mothers with young children learn from women friends how to write to Operation Santa Claus–though they have no idea where their letters go, or who reads them. As the children approach adolescence, they start writing on their own. They, too, are clueless about the giant cardboard boxes on 33rd Street.

According to postal employee Pete Fontana, who has headed the program for several years, some 10,000 donors are expected to make the trek to midtown this year to read letters, and they will choose 30,000 to 40,000 to respond to. In addition, hundreds of corporations will ask for as many as 500 letters each, to give to their executives and staff. And Fontana hopes for a replay of last year, when several Broadway productions took 20,000 letters–actors passed them out to audiences after the shows. In all, Fontanta estimates that a fourth to a third of the letters will be answered.

That means up to three-fourths will be ignored. These are the letters that, in performance artist Sharon Glassman’s words, are “resisted” by people like her because they fail to “sing.” Abandoned after Christmas in the big cardboard boxes, tone-deaf missives are eventually destroyed. Meanwhile, out in the zip codes, their authors are sorely disappointed.

“I don’t know if I still believe in Santa Claus,” says Cristina Gomez. She is a high school student from Washington Heights who wrote last year when she was 15, asking for patterned pantyhose. “I don’t know where the letters go or who reads them, but I thought somebody would come to the house. On Christmas I stayed home all day. Every time the doorbell rang I thought it was him. I gave up at two the next morning.”

Nevertheless, many letter-writers eventually learn how to make their letters sing–to “wassail through the mails.” They are extraordinarily sensitive to their donors’ emotional needs–which are nowhere more apparent than at the cafeteria-style tables on 33rd Street in December. There, as some letter-readers wipe their eyes with handkerchiefs, others purse their lips, struggling to discern which letters are sincere and which are fake. They might as well try to figure out the exact meaning of a Rorschach blot. The more they mull over the ink, the more they reveal of themselves.

“You can tell the scams,” insisted Westchester resident Adam Fuchs last December, after he had read several letters at the post office and picked a favorite to answer. “Like one says, ‘Hi, my name is Sarah. I’m 2 years old. My mommy just went through a divorce; she’s very sick. Can you please send a fur coat?'”

It wasn’t the fact that a 2-year-old can’t write. Rather, Fuchs implied, it was the fur coat, which he considered too luxurious for a poor woman to request from charity.

For a mother or adolescent to ask for stylish, brand-name clothing indicates selfishness and cynicism to many donors–even though the Santas may themselves be fashion plates. Last year, two young women in their twenties, who could have been extras on Sex and the City, pored over letters and grew wary. “This one wants a specific pair of shoes, with this and such color,” one said, frowning. “I get strange feelings from letters like that.” Another was from a 17-year-old boy lamenting that he got only one present the year before, and asking for a North Face coat this time around. He “annoyed” her, the young woman said, because “at 17 he should know” not to be complaining and asking for trendy clothes.

Donors also get nervous when a child requests a toy they consider vulgar, antisocial or frivolous. “One letter asked for ‘Grand Theft Auto,'” noted Jemma Roberson, a Harlem resident who was studying for a real estate career last year when she visited the post office with her toddler and toy Yorkie to read letters for the first time. Roberson wasn’t sure she wanted to give the boy the violent video game he asked for. “But is it right to substitute something else if the request is from the heart?” she mused. “Or is an adult taking these gifts–and maybe even selling them? I’m torn.”

Universally, donors say they are moved to go shopping by letters that express selflessness and the desire for goods that are useful, uplifting and not too ostentatious.

“Here’s one from a girl who says, ‘All I really care about is my family and don’t worry about me,'” said one of the Sarah Jessica Parker types. “I might adopt her.”

“Once we took a letter from a girl who wrote for her sisters but didn’t ask for anything for herself. We got her a Gap gift certificate,” said Flushing resident Cathy Webster, a graduate student in French literature at NYU. With her psychologist husband, Webster answers four to eight Operation Santa letters each year. “The first letter we ever took,” she said, “was from a single mom with a child in kindergarten and an infant. She asked for some clothes for herself, but mostly for the kids. It was very compelling.”

“In the one I’m taking this year,” said Adam Fuchs, “the kid is looking for a teddy bear for his sister and a teaching game–something that will help educate. That’s legit.”

“The ones I respond to,” says Bill Cressler, “start with ‘Hi Santa, how ya doing?’ Which I love. And they end with ‘Take care, Santa. Tell your wife I said hello. Love,’ and then the kid’s name. Beautiful! Beautiful!”

Cressler is a tall, bald, bearded man in his sixties who usually is executive assistant to the president of a real estate company, but takes off during the Christmas season to work at Radio City. For the past dozen or so years, he has been visiting the post office during the holidays and reading up to five dozen letters at a sitting. Participating in Operation Santa Claus, he says, takes him back to his own childhood in an impoverished but loving family in post-World War II Philadelphia. Unmarried and with no sons or daughters of his own, he enjoys conjuring a sense of family by participating in Operation Santa Claus.

Besides, he says, it’s essential to show disadvantaged New York kids that more affluent people care about them. “They’re not like I was when I was young. I didn’t know I didn’t have anything. Now they all watch TV and know what they’re missing! We cannot leave them feeling like that!”

These days, Cressler avoids letters from single mothers. “They’re often hard and self-centered: just I, I, I,” he said. At the same time, he is drawn to letters from children who seem to be living without fathers. “The kids never mention dads,” he says–another reason men like him should help.

But the help comes strictly during the Operation Santa ritual. Cressler never tells letter-writers his name, address or phone number, because hearing from them during the rest of the year can provoke intense anxiety. “Six years ago,” he said, “I sent a package with $200 worth of gifts to a single mother and put my phone number on it. She started calling me two or three times a week with ‘I have a $260 medical bill that welfare’s not paying. Can you pay?’ This went on for months. I said, ‘You’re abusing a wonderful program.’ She said, ‘If you have enough money to send me the stuff you did, why can’t you spring for another $260?’ I said, ‘Why?’ She said, ‘Because I don’t have it!’ I said, ‘But my taxes take care of that.’ I felt like Scrooge! Other people I’ve spoken to at the post office have told me they made the same mistake, of giving their phone number, and people called them for months afterward, asking for money.”

Shortly before being interviewed for this article, Cressler had spent several hours digging through the cardboard boxes until he found just what he wanted. “Dear Santa and Miss Santa,” began the missive that sang to him. “I am writeing you this letter to let you know that for Christmas if you can seand me a bike for Christmas. My name is Steve and I am 13 years old…. Think you! P.S. Merry Christmas. Your friend, Steve.”

Cressler didn’t trust the postal service with a bicycle, and he couldn’t find Steve’s phone number through Information, which he would need to arrange a personal delivery. Normally he calls the letter-writing child’s mother so he can “meet her outside the apartment building and give her the box; I want her to get the credit for being Santa.” Since he couldn’t contact Steve’s mother about the bike, he opted to send smaller gifts through the mail. He had no desire to actually meet the boy. Cressler never lays eyes on his young beneficiaries; instead, he enjoys “fantasizing how happy they’re going to be when they open my presents.”

Other donors put on Santa outfits and go into children’s homes. “Two years ago, a white couple from Long Island woke us up at 7 in the morning on Christmas,” recalls Josefina Cabral, a 35-year-old Dominican immigrant who lives with her three children in a noisy, scruffy apartment building in Inwood, and whose husband struggles to support the family as a wholesale candy salesman. “They had two children and they were wearing strange hats.” (“Mom, those were elf hats!” Cabral’s 7-year-old daughter explained, in Spanish.) “A woman came and brought a Christmas tree,” recalled cake decorator Dionora Fernandez, Cabral’s sister-in-law, who lives in the same building with her daughter Judi and two other children. “Another time, a man came with a boy and a girl.”

Donors who enact these visitations take pleasure–and often feel a sense of communion with–the reciprocal performance of their beneficiaries. Cathy Webster remembered delivering presents to a single mother in Astoria. “She came out to meet us and started crying, and I started crying, and she hugged us.”

Sometimes beneficiaries disappoint their donors. Fuchs recalled dressing up as Santa a few years ago and going to Jamaica, Queens, to deliver a package to some children whose mother had written on their behalf. When he gave her the gift, “she started screaming at me because she didn’t get what she wanted.” Ingrates like this mother, Fuchs said, make him “a little jaded.”

_______

But more often, supplicants play their roles perfectly, even when they compose their letters. Which is an amazing feat, considering that many have spotty writing skills, and such sparse contact with elite New York that they’ve never been to midtown, much less the James A. Farley General Post Office.

Take Steve Rivera, the 13-year-old who charmed Bill Cressler by greeting “Miss Santa” in his letter, and signing off as “Your friend.”

“Miss Santa was my idea,” says Daniel Rivera, Steve’s big brother. City Limits interviewed the two recently in Bedford Park, a rough part of the Bronx where graffiti often sports the word “gunz,” and apartment building foyers reek of urine.

Daniel and Steve, now 15 and 14 respectively, are friendly, talkative boys still waiting for their growth spurts. Their two-room apartment is so cramped that their parents sleep in the living room. Their mother is disabled, and their father, who worked for years as a machinist, now has arthritis and asthma and is jobless. The brothers have been sending letters to Operation Santa Claus since they were toddlers; their mother used to write for them. Some of her women friends showed her how, and suggested model wording.

Some of the language may have come from boilerplate letters–such as the epigraph of this article–that circulate throughout New York City. Each year, people sitting at the post office’s cafeteria tables cluck in bemusement at all the different pages torn from notebooks and all the various handwritings that say exactly the same thing: The most important thing I want is to give my childrens happiness sadly enough I can’t buy the basic thing in life…. Thank you, Santa Claus for making dream be come true. Postal workers are stymied about where this letter, and many other models, come from. Some are xeroxes of xeroxes of xeroxes, passed out at welfare offices, homeless shelters and schools.

Joseline Ovalles explains her technique. A Washington Heights mother of two preschoolers whose husband earns minimum wage in a factory, she learned about Operation Santa Claus shortly after immigrating from the Dominican Republic a few years ago. “Some friends told me about it,” she says. “I don’t write English, so at first my 10-year-old niece would translate for me and write the letter. Now a friend’s little girl does it.”

Last year, Ovalles began her letter by talking about how her two sons “are what I love the most,” but “because of some economical problems I can’t give them what they ask for they need a little bit of everything which is the reason why I’m writing you this humble letter.” After listing the children’s clothing sizes, Ovalles asked for coats for herself and her husband. She closed with, “Happy Christmas and a Happy New Year! We thank you beforehand.”

With letters like this, she gets packages every year. In addition, a little girl learns how to pen the maximally effective missive to Santa.

Boys learn, too. Today Steve and Daniel Rivera write their own letters, and take pride in coming up with just the right tone.

“Santa has a wife, so mention her,” advises Steve. “And when you ask for a gift, you should write, ‘I really need it, but if you can’t send it I’ll understand.’ And don’t ask for nothing t