Stripped of dignity, the unidentifiable remains of the Renaissance Casino & Ballroom, a historically important black cultural mecca once known as “The Aristocrat of Harlem,” are removed by wrecking machinery with the property’s former owner, the Abyssinian Baptist Church, framed in the background. (Claude Johnson)

The article excerpted below first appeared April 14 on the website of the Black Fives Foundation.

If one walks along Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Boulevard (aka Seventh Avenue) in Harlem today, they will see, for the first time in over 90 years, a vacant lot on the east side of the thoroughfare between West 137th and West 138th Streets.

The stained glassed windows on the west side of the Abyssinian Baptist Church, not seen from Seventh Avenue since the construction on that parcel of land in 1922 of the Renaissance Theatre & Ballroom, are now visible.

That historically important structure helped usher in the decade-long period of African American cultural and artistic flourishing, which at the time was known as the New Negro Movement. Those years eventually became known as the Harlem Renaissance period, and while many mistakenly believe that the building was named after the era, it was in fact the other way around.

Grand Opening

The Renaissance was one of the few social venues in Harlem designed, financed, built, owned, and operated by African Americans. Constructed by the Sarco Realty Company under the ownership of West Indian entrepreneur William Roach, the first stage of the project, which would eventually become a block-long entertainment complex that included stores and a theater, opened in 1921 at the corner of Seventh Avenue and West 137th Street. The theater hosted live orchestra performances of jazz , ragtime, and blues music, theatrical stage productions, and, of course, the latest photo productions. “This theatre should appeal to your sense of racial pride,” its grand opening announcement proclaimed.

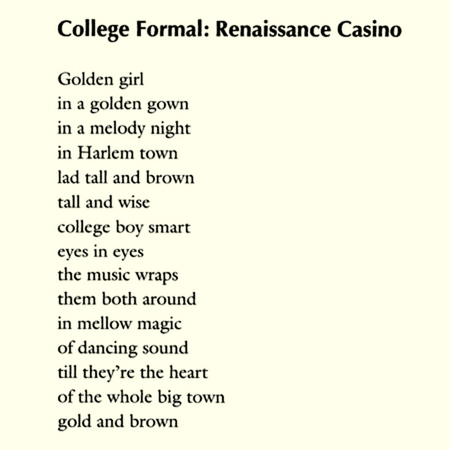

The ballroom portion of the complex opened in 1923, up the block at Seventh Avenue and West 138th Street, and immediately became popular as a hub for community events. Over the years it was the site of parties, fundraisers, assemblies, political rallies, dance marathons, wedding receptions (e.g. that of David and Joyce Dinkins in 1953), and formals. College formals held at the Renaissance Casino, in particular, were immortalized in a 1949 poem by Langston Hughes.

And, of course, since it was a ballroom, the site hosted all kinds of balls—debutante, cotillion, masquerade, and more—which featured music by live orchestras and house bands. Among the complex’s house bands were those of notable bandleaders Vernon Andrade and Fletcher Henderson. The construction of this ballroom opened a door for another kind of ball—basketball.

Black Hoops Mecca

Harlem had become the mecca for black hoops in the early 1910s, thanks to local African American teams like the Alpha Physical Culture Club, the St. Christopher Club, which featured Paul Robeson, the New York All Stars, the New York Incorporators, the Commonwealth Big Five, and the Spartan Braves. They played for more than a decade at the Manhattan Casino, a Jewish-owned 6,000-capacity dance hall, beer garden, and picnic grounds on Eighth Avenue at West 155th Street. Locally, the Manhattan Casino was the best, the most convenient, and the most affordable basketball venue north of Madison Square Garden. Fordham University, City College of New York, and Columbia all used it regularly, and the Public School Athletic League staged its high school city championships there.

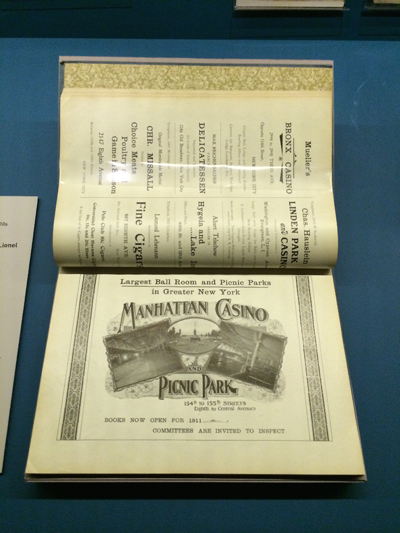

1910 advertisement for the Manhattan Casino from a souvenir program of the New York Schuetzen-Bund (Rifle Club) No. 1 Silver Jubilee, on display during the Black Fives museum exhibition at the New-York Historical Society. (The Black Fives Foundation Archives)

Its proprietor, a saloon entrepreneur named Eddie Waldron, was well-loved by black basketball team owners and promoters because he was consistent, reliable, and friendly, and by black Harlemites in general because The venue during the 1910s hosted iconic events such as performances by James Reece Europe, rallies by Marcus Garvey and Ida Wells, parties by Madame C.J. Walker, and fundraisers by Bert Williams, which helped plant and nourish important seeds of black culture that would soon blossom.

By the dawn of the Prohibition Era in 1919, the Manhattan Casino had become known as “The People’s Pleasure Palace” and “Waldron’s Palace of Mirth.” But that soon changed. To compensate for lost alcohol sales, Waldron was forced to jack up his basketball court rental fees. It escalated from $50 prior to Prohibition, to $200 the following year, to $500, a desperate amount, in 1922. This caused a mass exodus of African American business and culture, and the following summer the Manhattan Casino, by then in receivership, was repossessed by the Dollar Savings Bank of New York City.

Birth of the Rens

Among those most affected was Robert “Bob” Douglas, the owner of the Spartan Braves basketball, a national title contender, who now had to find a new home court. Douglas, a native of St. Kitts, did not have to look far. He reached out to the fellow West Indian owner of the Renaissance Ballroom, newly opened in 1923, and asked if he could use the dance floor as his home court. In return, he offered to name his team after the ballroom.

And that is how the New York Renaissance Big Five were born.

And that is how the Renaissance Ballroom, which gladly welcomed all of the Manhattan Casino’s displaced business, became Harlem’s mecca of African American cultural, social, community, and entertainment activity.

Douglas then instituted full-year, guaranteed, exclusive player contracts, making the Rens the first black-owned, all-black, fully professional basketball team. In the three decades prior to the formation of the NBA, the Rens dominated all of basketball, including the best white teams. During the 1932-33 season, they won 88 straight games in 86 days. In 1939, the Rens also won the inaugural World Championship of Professional Basketball, besting America’s ten top-ranked all-white teams. The 1932-33 squad collectively, and several of its players individually, as well as team owner Douglas, have been inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

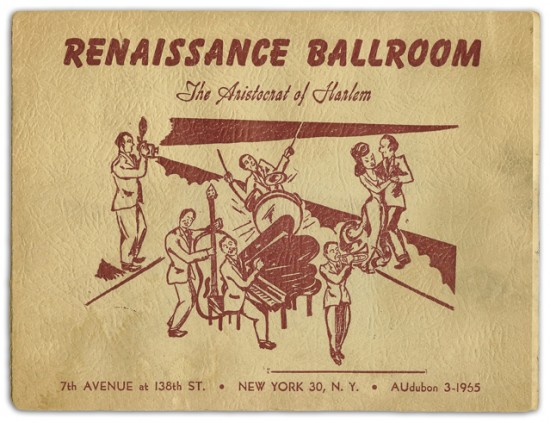

Aristocrat of Harlem

Just after the demolition of the property began on March 30, 2015, its newly vacated lot, encircled by an 8-foot tall green wooden construction wall and security fencing, contained mountains of unrecognizable rubble—twisted metal, crushed concrete, broken bricks, and other debris—all that is left of the building once considered to be the real estate anchor of Seventh Avenue and which was fondly known as “The Aristocrat of Harlem.”

The Renaissance Ballroom thrived as a hot spot well into the 1960s, even after the demise of the New York Rens in 1949, and was managed all of those years by the team’s former owner, Douglas.

College formals held at the Renaissance Casino were immortalized in this 1949 poem by Langston Hughes. (“Collected Poems of Langston Hughes” by Langston Hughes)

The Renaissance complex closed down in the 1970s, stood abandoned for a time, and was subsequently purchased by a white real estate speculator who leveraged a very favorable loan from Ensign Savings Bank. When that bank went under during the savings and loan crisis of the late 1980s, the federal Resolution Trust Company, formed to auction off the assets of the various defunct banks, disposed of Ensign and all of its assets, including its mortgages, which included the mortgage on the Renaissance buildings.

Abyssinian Baptist Church

It was at this time that the property’s prominent neighbor, the Abyssinian Baptist Church, under its pastor the Reverend Dr. Calvin O. Butts, III, became interested in acquiring the historic buildings. They assembled a group of Harlem-based business people (including Ed Myers, Thelma Goodrich, George Weldon, Lee Dunham, Matt Brown, Herman Lee, and Curtis Mills, most of whom are now deceased) who each put up around $25,000 to create an entity called the Renaissance Complex Redevelopment Corporation (RCRC). Meanwhile, the church had established a real estate arm in 1986, the Abyssinian Development Corporation (ADC), to help develop various other properties in Harlem. This entity was incorporated in 1989.

To pave the way for the acquisition, Abyssinian Baptist Church then loaned $100,000 to ADC, to be loaned to RCRC, and with this capital church officials under the direction of Rev. Butts asked federal lawmakers and agency executives, including Congressman Charles Rangel, it is said, to see if the Resolution Trust Corporation could extract the Renaissance mortgage from the bulk auction of its assets, an action that would make the mortgage available to be sold at an individual auction. The request was granted, and after an auction at which it was the only bidder, RCRC became the owner of the property in the early 1990s. Also, since ADC technically served as an advisor partner to RCRC on the Renaissance complex development, it therefore was eligible to receive a federal Office of Community Services Grant to hire an architect to develop plans. Throughout the 1990s and into the early 2000s, ADC used these plans in attempts to secure an operator for the building.

One of a series of exterior views of the abandoned Renaissance Ballroom in Harlem, New York City, prior to its recent demolition. (Claude Johnson)

During the intervening years, while hundreds of thousands of tourists from all over the world flocked to Abyssinian to attend church services and view Harlem culture on display in the form its outstanding choir, the public, including community residents as well as church congregants, fully expected ADC to preserve and restore the Renaissance property. That’s because this is what church officials repeatedly stated.

The historically and culturally priceless Renaissance Ballroom, once called “The Aristocrat of Harlem,” is reduced to a pile of rubble at the foot of the adjacent Abyssinian Baptist Church, which once led an effort to redevelop it. (Claude Johnson)

3 thoughts on “Renaissance Lost: Requiem for a Demolished Harlem Shrine”

Pingback: 50 Years of Fighting to Save New York City’s Historic Architecture – Hyperallergic | Glamour Party

Pingback: 50 Years of Fighting to Save New York City’s Historic Architecture – Hyperallergic | Architecture

Pingback: A look at once-hot NYC nightclubs that were forced to shutter up - Age Times | World News, Politics, Economics, Entertainment,Sport,Business & Finance | Age Times | World News, Politics, Economics, Entertainment,Sport,Business & Finance