While the last decade has seen cleanup efforts planned or launched at some of the city’s most polluted waterways, like Gowanus Canal and Newtown Creek, the community has struggled to get traction for a comprehensive cleaning plan for Coney Island Creek, despite its continued recreational use and multiple requests for action by local leaders.

Nina Dietz

Locals take advantage of a sunny Saturday afternoon in April to see what they can catch off of the Kaiser Park fishing pier at Coney Island Creek.Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of three stories examining the history of pollution and calls for remediation at Coney Island Creek.

Coney Island Creek is approximately two miles long and before the 1920s, when infill divided it in half, used to connect Sheepshead Bay to the Verrazano Narrows, cutting Coney Island off from the rest of Brooklyn. Derrick Batts has owned and operated the Coney Island Hook and Bait Shop—the only bait shop on the peninsula—for nearly seven years.

In the summer, people flock to Batts’ shop on their way to the creek, where old women watch crab pots from the water’s edge and fearless kids play in the boat graveyard off Calvert Vaux Park. Batts sells out of worms by midday nearly every day during the busy season. It is a lively place.

But what the people who swarm the creek every summer may not know: they are swimming and fishing from a site so polluted that for years it has been a concern among community organizers, and state and federal officials.

Coney Island Creek was historically a hub for many polluting industries, which left behind a toxic legacy in and around the waterway. DDT has been found off the southwest banks, PCBs throughout the north end, and lead is a constant contaminant beneath storm pipes.

This kind of past pollution is common to the waterways of New York City. But while the last decade has seen cleanup efforts planned or launched at many of these sites, like Gowanus Canal and Newtown Creek, the Coney Island community has struggled to get traction for a comprehensive cleaning plan for Coney Island Creek, despite its continued recreational use and multiple requests for action by local leaders.

While the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) did a Preliminary Assessment of the creek in 2020, three years later, a decision still hasn’t been made on whether the agency will add the waterway to its National Priorities List (NPL).

“I think that people don’t respect the creek. I think that they don’t appreciate the creek,” said Ida Sanoff, a longtime resident. “A lot of people, you know, they just don’t care.”

Living with a toxic legacy

Ida and Jeff Sanoff have lived on the Coney Island Peninsula for nearly their entire lives. The duo, always invested in their neighborhood, have been on the board of Brooklyn Community Board 13 for over a decade now.

Every few years Ida Sanoff hears that her friend Gene Ritter has once again made the news. He is a diver who is frequently pulling up remnants of the creeks’ history from the sediment: in 2010, Ritter found an empty five-foot-long World War II era copper artillery casing. In 2012, he made headlines for finding an entire sunken WWII warship.

Nina Dietz

The “boat graveyard” near Calvert Vaux Park. Hulls pepper this section of the creek, with some even washed up on the beach.For Sanoff, those finds are just another reminder of the contaminants, some of them toxic, swirling in Coney Island Creek. Based on the location of the vessel, near Calvert Vaux Park, it likely came from the old Wheeler Shipyard, which specialized in yachts and small commercial vessels but switched to constructing mostly sub-chasers during WWII.

The Coney Island Wheeler shipyard closed permanently in 1948. It was one of multiple shipyards that peppered the creek in its heyday, some of them reportedly having survived into the 1960s. Many of the shipyards also engaged in the demolition of decommissioned vessels, or shipbreaking, according to local historian and lifelong resident Charles Denson. The Wheeler Shipyard is just the best documented, as it was the production site of Ernest Hemmingway’s personal yacht, the “Pilar.”

Jeff Sanoff knows Coney Island’s maritime history is just one of the ways pollutants have made their way into the creek over its long industrial past.

The ghosts of these former industrial sites keep coming up on the community board agenda. And as heads of Brooklyn Community Board 13’s environmental committee, it falls to the Sanoffs to deal with them. Aside from Coney Island Creek itself, there are three sites on the banks of the waterway currently under investigation by the EPA.

The sites—T & J Auto Salvage, Coney Island Electroplating Works and the Cropsey Scrap Iron & Metal Corporation—underwent Preliminary Assessments in 2020, the first step to see if they qualify for the National Priorities List, used “to guide the EPA in determining which sites warrant further investigation.” All three are still awaiting decisions.

Despite this, Coney Island Electroplating Works is moving forward with a clean-up as part of an administrative settlement reached by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and property owner in July. Also, according to Andrew Guglielmi, director of remediation at the DEC, the owners of the former T&J Auto Salvage facility have agreed to enter a voluntary brownfield cleanup program with the state, so the site has been transferred to DEC control. That agreement was finalized in March.

Of the three businesses evaluated by the EPA in 2020, only Cropsey Scrap Iron & Metal Corporation is still open. It is unclear whether remediation there will be handled by the federal or state government, or if remediation will happen at all.

A fourth site, Decor by Dene, sits less than half a mile from the edge of the creek. Though most recently home to a lighting manufacturer, it has also been the site of a furniture maker, lacquer sprayer, and plastic bag producer since the property was developed in the mid 20th-century. A Preliminary Assessment by the EPA in 2017 showed it was in need of remediation, but should be within the bounds of state’s authority. It has since been officially passed off to the DEC for clean-up.

Decor by Dene is just across Shell Road from the MTA Coney Island Maintenance & Overhaul Shop, located in a section of the larger Coney Island Rail Yard, the southernmost tip of which is only about 50 meters from the banks of Coney Island Creek. For years, the rail yard has sent runoff into the waterway—an unknown mixture of oil, grease, metal cleaners, lead, and other chemicals used to maintain New York City’s subway cars—until the MTA installed a water filtration system as part of a 2021 construction project.

The sheer amount of lead found in the creek’s surface sediment is shocking. Following the 1992 Nor’easter, between 1994 and 1995, the Army Corp of Engineers designed and built the Coastal Storm Risk Reduction Project, adding evenly spaced small jetties, known as beach groins, and significant amounts of sand to replace what had been washed away in the storm.

Seagate, the beach-fronted neighborhood at the tip of the peninsula, opted against the beach groins. The overall beach widening and comparative narrowing of Seagate led to a change in the flow of Coney Island Creek. Sanoff says over time this has started to form a natural sand cap, burying pollutants collected at the mouth of the waterway. It also means that sediment is constantly accumulating, causing lead to build up very quickly at storm drain outfalls.

It was a significant enough problem to halt the city’s plans for a new ferry route connecting Coney Island to Manhattan. Despite spending millions to build a landing in Kaiser Park, the city’s Economic Development Corporation suspended the project in 2021, citing “navigation and safety concerns related to sand build-up.”

The landing’s location on the creek side of the peninsula had spurred protests from local residents, who worried the dredging required to keep the waterway passable for boats would unearth long-buried pollutants. “The creek contains a host of highly toxic legacy contaminants from prior industrial tenants, is a discharge point for untreated sanitary sewage, stormwater and floatables, and periodically floods over, ” the advocacy group Coney Islanders for an Ocean Side Ferry wrote in a letter to Mayor Eric Adams last year.

Nina Dietz

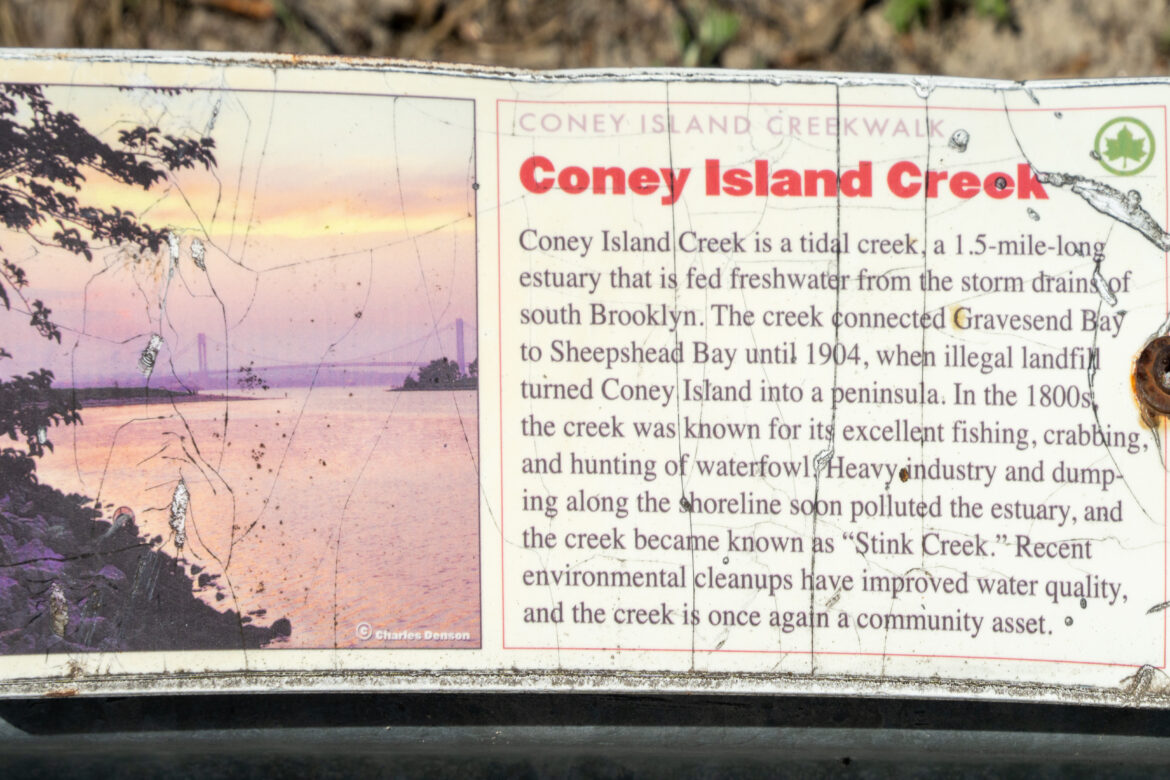

A Parks Department sign on a guard rail separating Kaiser Park from the creek recalls the waterway's industrial history, and its moniker "Stink Creek."‘Sandy took everybody off guard’

That sand buildup also became a problem in 2012, during superstorm Sandy, when much of the flooding came from the creek side of Coney Island. Residents have reported a persistent cough they called the “Coney cough,” from the small particle sediment that washed up from the creek and later, from the mold.

“Sandy took everybody off guard. Everything was washed up with that flooding. Everything. There was kitchen furniture, there were boats, there was everything,” Ida Sanoff said. “There was whatever sediments had washed up and dried and become aerosolized. And everybody had a cough. And it went on for months.”

Some people never shook their coughs. Though not studied in Coney Island, other areas affected by Sandy tracked asthma and respiratory illnesses and mold exposure after the storm and found similar impacts. It took years for the creek’s storm drains to be cleared out.

Though most of the industrial sources of Coney Island’s pollution are now gone, there is an active scrap metal yard and several iron workshops still operating less than a block from the creek, as well as an electronics manufacturer. The community continues to use the creek for subsistence fishing, educational school programs, and baptisms for local churches.

Sanoff wants the contamination addressed before the next flood comes. “It's sort of one step forward, two steps back. But that's the only shot we have: nobody else is gonna come in and voluntarily clean this thing up,” she said. “It's sad, and I don't understand. I don't understand how it's been ignored and neglected to this point.”

Read the Next Installment: The Quest to Clean Up Coney Island Creek, Part 2—Long Road to Superfund Status

To contact the editor, email jeanmarie@citylimits.org