Families will be eligible for a supplemental payment this fall if they received the Empire State Child Credit when they filed 2023 tax returns. However, experts say the formula used to calculate payments is inequitable and excludes the lowest-income families from the maximum credit.

William Alatriste/NYC Council Media Unit

State Sen. Andrew Gounardes, who sponsored a bill that would create a more encompassing Working Families Tax Credit, at a rally pressing for it in 2023.Lea la versión en español aquí.

The recent unveiling of the $237 billion New York State budget has stirred controversy, particularly around tenant stability and environmental issues. And local advocates are adding another item to this list of budget disappointments: a chance to cut child poverty in New York.

While this year’s budget deal includes approximately $350 million for supplemental payments under New York’s Empire State Child Credit (ESCC)—for which families with mixed immigration status and Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN) filers may be eligible—it left out a more expansive plan that many anti-poverty advocates had been pushing for.

That proposal would create a new Working Families Tax Credit to replace the ESCC, offering households a minimum $500 credit per child regardless of income level (as compared to the current ESCC, under which the maximum credit a one-child household can earn is $330).

Still, advocates welcomed the $350 million allocation as good news, because families in need will receive money in the fall. A similar supplemental ESCC payment was included in the 2022-2023 budget.

“The supplemental payment was the way that they could say, ‘We are still going to include something for families in this budget,’” Liza Schwartzwald, director of economic justice and family empowerment for the New York Immigrant Coalition, said on April 19, as details of the budget agreement were being finalized.

A quarter of the city’s children lived in poverty in 2022, as did 23 percent of adults, according to a Robin Hood report—doubling the national poverty rate of 12 percent. That’s an increase of nearly 500,000 people from 2021, an uptick researchers attributed to the end of pandemic-era public benefits.

During late budget negotiations in Albany, poverty experts and advocates learned that no permanent changes to family tax credits would be included. Instead, legislators were considering an ESCC supplemental payment, which had been included in the Assembly’s one-house budget proposal.

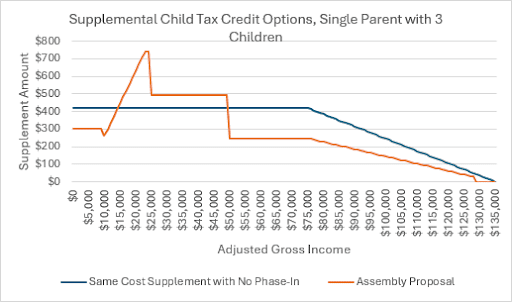

For distributing the supplemental payment, the Assembly had proposed an option (illustrated by the orange line in the chart below) that increased or decreased based on income. But advocates put together an alternative they argued would be more equitable: a flat payment to all families earning roughly $80,000 or less, with reduced payments for higher earning families proportional to their income (illustrated by the blue line in the graph below).

Liza Schwartzwald/New York Immigrant Coalition.

The Assembly option (illustrated by the orange line) for distributing the $350 million in ESCC supplemental payments compared to one put forth by anti-poverty advocates (blue line) which they argue would have been more equitable.That option “is probably the more understandable of the two when it comes to families, and the one that would have the higher impact on poverty reduction,” said Schwartzwald. That’s in line with the state’s commitment to reduce child poverty by 50 percent over 10 years, passed as part of the Child Poverty Reduction Act in 2021.

However, the final budget included the Assembly’s distribution plan, which comprises only a one-time payment that varies significantly—and, in the opinion of several experts and advocates, arbitrarily—based on income, with payment ranging from 25 to 100 percent of credit they received with their 2023 taxes.

In addition, it excludes the neediest families from earning the highest possible credit due to a “phased-in” income requirement the ESCC inherited from the federal Child Tax Credit, critics say.

The phase-in component means that “no family earning below $9,667 per year can receive the full credit,” complained Pete Nabozny, policy director of The Children’s Agenda. “Families with multiple children do not receive the full credit until their income is much higher.”

As part of the New York State Child Poverty Reduction Advisory Council (CPRAC), researchers with the Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University made seven recommendations for changing the ESCC, including eliminating the phase-in component.

Nabozny estimates that most families will receive a credit of between $82.50 and $247.50 per child. The office of Gov. Kathy Hochul estimates that over 1.5 million New Yorkers would receive an average benefit of $223.

| Total Supplemental Payment Amount | ||||

| Number of Children | ||||

| Adjusted Gross Income | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| $5,000 | $100 | $200 | $300 | $400 |

| $20,000 | $248 | $495 | $631 | $631 |

| $45,000 | $165 | $330 | $495 | $660 |

| $65,000 | $83 | $165 | $248 | $330 |

| $85,000 | $0 | $124 | $206 | $289 |

| $105,000 single | $0 | $0 | $124 | $206 |

| $105,000 married couple | $83 | $165 | $248 | $330 |

Nabozny and Loris Toribio, a senior policy advisor for anti-poverty nonprofit Robin Hood, also point out that under the distribution plan, just one additional dollar of earnings could cost some families hundreds of dollars.

A three-child family earning $24,999 a year could receive a $743 supplement. However, if the family earns only one additional dollar, they will only receive $495, thanks to the steep dropoff in how the payments are formulated.

“A very drastic change,” Toribio noted. “It’s not the most elegant way to design the supplement.”

Gov. Hochul’s office, Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie and Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins did not respond to questions about the payout structure included in the budget deal.

State Sen. Andrew Gounardes, who introduced the bill that would establish the Working Families Tax Credit (WFTC)—which would consolidate the Empire State Child Credit, Earned Income Tax Credit, and exemptions for dependents into one omnibus tax credit—also did not provide much detail on how the decision was made.

“As budget negotiations came to a close and it became clear we weren’t going to get the full credit, we learned that what was being included in the final budget was the orange line,” said Gounardes in an email.

“We fought at the 11th hour to change the credit to the blue line, because as you point out, it’s more equitable. But we weren’t able to get that change,” he added. “We’ll be fighting for this again next year.”

On April 24, the NY Can End Child Poverty group released a statement acknowledging some wins in the budget, including $50 million in one-time funds for Buffalo, Rochester, and Syracuse, but said it still falls short of what’s needed.

“A lack of investment in poverty-fighting measures isn’t just a missing line in the budget,” reads the emailed statement. “It’s felt by the family stretching to afford rent and child care, it’s felt by a child going without school lunch, and it’s felt by families deciding whether New York is a place where they can afford to raise their children.”

Experts consulted by City Limits said that legislators and the governor should have taken advantage of an opportunity to correct some of the structural issues with the ESCC, instead of adopting a clunky one-time supplement for the second budget in a row.

“To truly turn the tide on child, family, and community poverty will require sustained investment,” said Dorothy (Dede) Hill, director of policy at the Schuyler Center for Analysis and Advocacy.

“So too, to meet… NY’s agreed upon goal under the Child Poverty Reduction Act of cutting child poverty in half in a decade, will take significant, sustained state investment, not one-time bumps in the state child tax credit,” Hill said via email.

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Daniel@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

Want to republish this story? Find City Limits’ reprint policy here.