Gov. Hochul tried to water down a bill that sought to stop companies that have contracts with the state government from contributing to tropical deforestation. Now, lawmakers plan to reintroduce the bill and fight for its integrity.

Kevin P. Coughlin / Office of Governor Kathy Hochul

Gov. Kathy Hochul speaking at a climate-related press conference in 2022.Two days before Christmas, Gov. Kathy Hochul vetoed the first bill in the United States designed to regulate the supply chains of companies that do business with the state, ensuring products don’t come from tropical forests that have been wrecked by deforestation.

The legislation passed with majority support in the State Senate and Assembly in June of last year. But Hochul delayed signing it into law and proposed last minute amendments that the bills’ advocates refused to accept, claiming it would render the legislation useless.

Now the bill’s sponsors, Senator Liz Krueger and Assemblymember Kenneth Zebrowski, say they plan to re-introduce it in 2024, although details are yet to be ironed out.

“It won’t be identical to last year’s [bill]. But it also won’t be the extremely watered down version that the governor attempted to negotiate because we were not going to sign off on a bill that would not meet our international obligations,” said Sen. Krueger.

Deemed the Tropical Deforestation-Free Procurement Act, the bill hopes to curtail the practice of clearing forested land, which contributes to around 10 percent of global warming and desecrates natural habitats across the world.

Under the legislation, corporations would be obligated to trace the origin of the products they sell to the government and ensure they are not derived from areas that have been deforested or degraded since Jan. 1, 2023.

The bill would require contracted companies to provide details about their supply chain and give local regulatory authorities access to “records, documents, agents, employees or premises” whenever necessary to prove their compliance.

Those that didn’t comply would be subject to a penalty of at least $1,000 or could lose their contract with the state all together if the authority responsible for government contracts, the state’s Office of General Services, saw it fit.

But Hochul’s suggested changes would have allowed corporations to bypass the state’s ability to closely inspect a company’s supply chain, advocates told City Limits.

In Hochul’s version, companies could simply present a certificate issued by a third party that claims their supply chain is deforestation free. The governor also wanted to include language that could exempt contracted companies from following the rules.

“I understand the need for compromise. I get it. I’m a legislator. That’s what we do every day of the week,” said Sen. Krueger. “But I’m not interested in bills that are for show. I’m interested in big picture policy legislation that moves the ball down the court in the right direction.”

At the negotiation table

As soon as the Tropical Deforestation-Free Procurement Act passed in both houses in the summer of last year, Sen. Krueger reached out to Hochul’s office and the agencies affected by the bill to make sure they didn’t have any “problems” with the legislation.

“No one would talk to us,” Krueger lamented.

NYS Senate Media Services

State Sen. Liz Krueger, who sponsored the Deforestation bill in the Senate, speaking in 2022.In December, the administration finally sent a list of proposed amendments. And one of them in particular stood out to Krueger and the bill’s supporters.

Instead of having the state vet the company’s supply chain, Hocul’s version would clear companies to do business with the state if they presented certification issued by outside organizations.

“There are lots of companies that do this. And yet it has not contributed to any meaningful decline in deforestation,” said Vanessa Fajans-Turner, executive director of Environmental Advocates New York and one of the bill’s supporters.

Fajans-Turner points out that while there are good certification systems out there, many have been accused of greenwashing, a practice of falsely advertising that a company is environmentally friendly when it’s not.

A recent investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) concluded that the sustainability industry often “overlooks forest destruction and human rights violations when granting environmental certifications.”

In a memo issued when the bill was vetoed, the governor admitted that “there are not yet reliable third party certifications that can effectively trace such ingredients through the supply chain.”

“Third party [certification] systems are hard to control, because anybody can create one. So it’s much better and it sends a much clearer signal to the market when a government says: “Here’s what we want, here’s what we don’t want,” Fajans-Turner explained.

New York’s Tropical Deforestation Act sought to avoid the trap of faulty green certification by having the state do the vetting process directly. For the bill’s advocates, taking out that mechanism would mean the bill fails to serve its purpose.

“Environmental advocates wanted to make sure that the bill was not something that amounted to greenwashing. We don’t advocate for bills to get passed and signed just to say we did it. We want meaningful bills,” Fajans-Turner said.

But the Office of General Services (OGS), the agency that oversees state contracts and would be responsible for implementing the new rules, pushed back on the idea of putting the state in charge of regulating supply chains. It claimed that enforcing compliance in several aspects of the legislation would cause too much of a strain for the agency, lawmakers and advocates of the bill told City Limits.

“We will review the bill if and when introduced,” OGS said in an emailed statement.

The idea of a government-led vetting process was modeled after the European Union’s own regulation on deforestation-free products. Last year, a law went into effect across Europe that requires all companies, not just ones that have a contract with the state, to verify that products placed on the market don’t come from deforested areas.

Companies like Sysco, the world’s largest food distributor, are gearing up to comply with the European Union’s new rules. But they have made it clear that they were unhappy about having to comply with a similar law in the U.S. The company told the bill’s advocates that making changes to New York State alone would cause a logistical hurdle for U.S suppliers since they would be out of sync with the rest of the country.

Four months after the deforestation bill passed in New York, Sysco registered to lobby Hochul on the legislation. The corporation has more than $200 million in contracts to provide food to various state agencies that come from tropical forests like coffee, cocoa and palm oil—and clear links to deforestation, according to reporting by NY Focus.

Sysco has not publicly taken a stance on the bill and did not respond to City Limits’ request for comment.

But the food distributor and other companies have claimed that they are unable to accurately identify the origins of their products through each step of the supply chain.

“Most businesses supplying products to the state are not manufacturers and do not have access to that information for every ingredient of their product,” Gov. Hochul said in her veto memo.

It added that “imposing” the “burden” of businesses tracing the origin of their commodities, “would drive them away from doing business with the State and put at risk important government operations such as our ability to provide food to individuals in the care and custody of the State.”

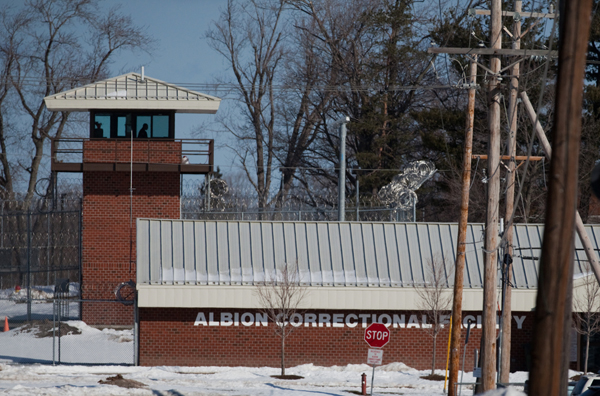

Marc Fader

Albion Correctional Facility in upstate New York. The Deforestation bill would look to regulate the supply chains of companies doing business with the state, such as those contracted to provide food for people incarcerated in state prisons.At one point during negotiations, Hochul’s team pointed out that the state would, for instance, have to stop buying Girl Scout Cookies. The cookies contain palm oil, an ingredient that is typically sourced from deforested areas.

“It turns out that you can make delicious cookies without palm oil and many companies of the world do so,” Sen. Krueger told City Limits. “I’m thinking of starting a petition and seeing how many smart young girl scouts would prefer we save the planet versus maintaining the current recipe for Girl Scout Cookies.”

‘To the best of our knowledge’

When the bill gets reintroduced this session, the legislation’s sponsor in the State Assembly, Kenneth Zebrowski, says he expects to see “very similar push back” from companies like Sysco, but despite that, believes it’s worth putting up a fight.

“When a state like New York gets large companies to amend their practices then it becomes much easier for everybody else to amend their practices as well. It sets the stage for compliance. And when you combine that with a big entity like the European Union, then you really start to have global effects,” Zebrowski said.

Getting large companies to comply, however, would have been very difficult if Hochul had signed the version of the bill that her administration was pushing for, advocates told City Limits.

In several of the more than a dozen drafts that were passed back and forth between Hochul and the leigislation’s sponsors, the governor wanted to include language that could exempt corporations from following the rules.

Adding clauses like “to the best of our knowledge,” for instance, would have allowed companies and regulatory agencies alike to turn a blind eye and say that they didn’t know that bad practices were taking place in the supply chain, and therefore could not be held accountable.

“That was a huge loophole for what we would call plausible deniability, where a company could simply say we didn’t know that their supply chain was linked to forest destruction or abuses of human rights. And they’d be off the hook,” explained Jeff Conant, an advocate of the legislation and director of the international forests program at Friends of the Earth.

“[Hochul’s team] would not budge on taking out language that seemed intent to create broad, vaguely worded loopholes throughout the bill that would limit or negate any practical impact the bill might have had,” Conant added. “Governor Hochul didn’t just let down those of us who are engaged directly to make this bill happen. She let down the indigenous communities across the tropics who are fighting to protect their lands and their cultures and their very lives.”

Brazil and Indonesia’s tropical forests account for almost half of the world’s deforestation. In Brazil alone, where indigenous communities have lost the forests they call home, more than 4 million acres of forest were cleared in 2022, a 21 percent increase from 2021.

The Tropical Deforestation-Free Procurement Act had also sought to close loopholes in a 1995 state ban on the use of tropical hardwoods, something the governor’s office resisted.

“There is no evidence that State or local agencies have misused or abused any of the existing exemptions, and removing these exemptions in situations where no practical alternative materials are available would impose additional costs on State and local governments, potentially leading to cuts in important services,” Hochul said in a memo.

When the bill gets re-introduced in this legislative session, lawmakers say they hope to negotiate with the administration to find a way forward.

Gov. Hochul’s office did not comment on last year’s negotiations, but said in an emailed statement that “the Governor will review all legislation that passes both houses.”

“It’s probably premature right now to say exactly what our tactics will be in the new year,” said Zebrowski. But, he added, “this will remain a priority for both us and the environmental community.”

“The degradation of our forests is something that is a worldwide threat to the environment,” he said. “We are obviously a large state with a large economy. And I think we can be part of the solution, and not part of the problem.”

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Mariana@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org