The Tropical Deforestation-Free Procurement Act would be the first in the U.S. to regulate local companies’ supply chains and require they’re free of products sourced through deforestation. But Gov. Hochul, who has until the end of the year to sign it into law, is touting a revised version that supporters say would render it ineffective.

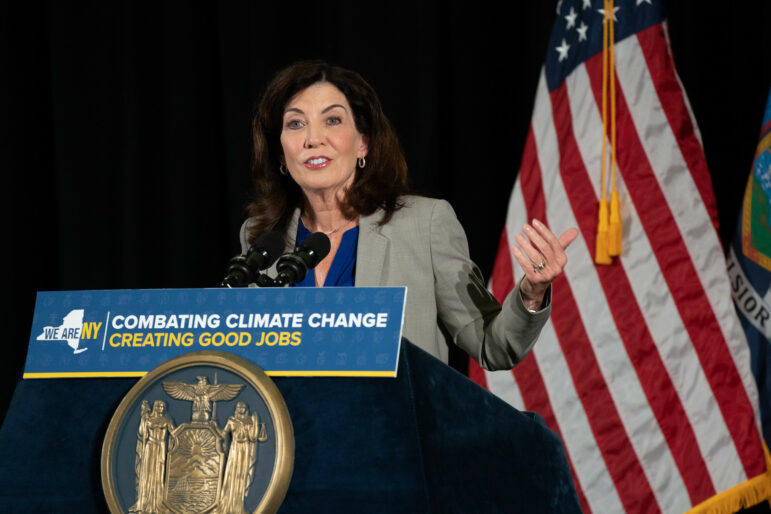

Flickr/Governor Kathy Hochul

Gov. Kathy Hochul at a climate-related press conference in 2022.Gov. Kathy Hochul is yet to sign a bill, passed by lawmakers this summer, to stop companies that have contracts with the state government from contributing to tropical deforestation.

This week, Hochul’s team sat down with supporters of the bill and presented them with a “gutted” version of the legislation that would essentially render it useless, advocates who had access to the proposal told City Limits.

“[Hochul] is proposing some chapter amendments and my staff have just started to review them, so I’m not at a point where I’m prepared to comment on them,” the bill’s sponsor, State Sen. Liz Krueger, told City Limits.

“But what I’ve heard so far from the advocates, frankly, is that her first proposal would not be acceptable,” Krueger added. In an emailed statement, Hochul’s office said that the governor “is reviewing the legislation” and made no further comments.

Known as the Tropical Deforestation-Free Procurement Act, the bill hopes to curtail deforestation, which contributes to around 10 percent of global warming.

It also sets a precedent: it is the first bill in the United States to regulate local companies’ supply chains and require they’re free of products sourced through deforestation—the intentional clearing of forested lands, a practice that is devastating habitats across the world from Africa to South America.

Under the legislation, corporations that sell to the government would have to trace the origin of their products and ensure that they are not derived from areas that have been deforested or degraded since Jan. 1, 2023.

Targeted products, the bill says, come from commodities “produced on land where tropical deforestation” has taken place “or is likely to occur” like coffee, cocoa, and palm oil, which is used to make a variety of processed food. Companies like Nestle, PepsiCo and Sysco, for example, sell food made from these resources to the state through contracts they have with government agencies like the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision.

The bill also covers tropical hardwoods that end up in places like boardwalks, docks, park benches and railroad cross ties. These hardwoods are derived from tree species like the Ipe and Pau Rosa, which are found in the Amazon, the world’s largest tropical rainforest. In Brazil alone, more than 4 million acres of forest were cleared in 2022, a 21 percent increase from 2021.

To trace the origin of these company’s products and make sure they are deforestation-free, the law would give the NYS Office of General Services (OSG) the power to regulate their government contracts and require that corporations submit details about their supply chain to do business with the state.

Companies would be forced to “cooperate fully” with the OGS and other regulatory government authorities by providing access to “records, documents, agents, employees or premises” to “determine the contractor’s compliance,” according to the legislation.

But the state’s ability to force companies to trace the origin of their commodities may be compromised if Hochul’s newly version of the bill gets signed into law, supporters say. Advocates who reviewed the governor’s proposal told City Limits it would take away the OSG’s oversight power.

“We are worried it would wipe out all of the regulatory requirements that were written into the original bill, meaning the state would have zero responsibility for actually implementing the bill,”said Jeff Conant, an advocate of the legislation and director of the international forests program at Friends of the Earth.

“We fear that their proposal in the bill right now is that we take out anything that requires companies to show that they’ve done due diligence around deforestation,” he explained. “For Hochul to weaken this bill, in any way, is to undermine any commitment she may have to climate, to the environment, and to human rights.”

Vanessa Fajans-Turner, executive director of Environmental Advocates NY, echoed this sentiment at a press conference Thursday. “What we have seen so far” she said, of the governor’s proposal, is “a bill that presents more of the latter, a shell without a lot of substance.”

“Our priority as advocates in the community is to come out with a bill that is strong. We are past the point of half measures or empty measures,” Fajans-Turner said.

Hochul’s version would also remove language in the legislation that sought to close loopholes in a 1995 state ban on the use of tropical hardwoods. It would topple, for instance, an added clause that said the list of banned hardwoods would “include” but not “be limited to” the original list of banned species.

The bill has its critics: This fall, four months after it was passed, the world’s largest food distributor, Sysco, registered to lobby Hochul on the legislation. The corporation has more than $200 million in contracts to provide food to various state agencies—and clear links to deforestation, according to reporting by NY Focus.

Other groups, like the Empire State Forest Products Association—a trade organization that represents hundreds of New York wood product manufacturers—argued in a March opposition memo that the bill’s requirements “may involve considerable changes for the industry, with increased transaction costs from the bottom to the top of the supply chain.”

But the version of the Tropical Deforestation-Free Procurement Act that passed in the New York State Legislature in June has strong supporters around the world. Lawmakers, advocates, and business leaders at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 28) made a plea Thursday at a press conference in Dubai for Hochul to sign the bill, as it was written, into law before the end of the year.

“Several countries promise that they will create mechanisms to stop products from deforested areas from making their way to their countries, but none of them have managed to reach that goal,” Dinamam Tuxa, coordinator of the Articulation of the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB), told City Limits at the press conference, which was streamed online.

“These laws don’t contain mechanisms to properly trace these products and properly penalize these companies. So this law brings hope that we will be able to put that into place to protect our territories,” he added.

This isn’t the first time global leaders in the environmental community have defended the law. Last year, it garnered international support when over 670,000 people signed a petition to urge New York State to “to stop global imports from deforestation.”

Signing the law would allow the United States to join countries in the European Union that are enacting similar regulations. Last year, the EU passed a regulation that requires all companies, not just ones that have a contract with the state, to verify that products placed on the market are deforestation-free.

Starting in June of this year “operators and traders will have 18 months to implement the new rules” that will require them to prove that their products “do not originate from recently deforested land or have contributed to forest degradation.”

While New York’s bill is not as all-encompassing as the EU’s regulation, advocates say it is a step in the right direction that could trigger other states in the U.S. to follow suit. “I think that there are other states throughout this country who are watching to see what New York does,” said Sen. Krueger.

It would be “a huge victory” if the bill “is signed in the way that it was written,” the senator said, not just because it would encourage other states to adopt their own regulations, but because it would send a strong message to the world.

“Sometimes it’s hard as New Yorkers to actually see the cause and effect of our purchase policies, and [how they contribute to] the destruction of some of the most valuable environmental properties in the world because we want cheaper soybeans or cocoa plants, or coffee,” Krueger explained.

“So really what this bill is saying is that we need to be aware of the damage that is going on,” she added. “And we must play a role as a government and say: no, we’re not going to be a part of this.”

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Mariana@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org

One thought on “Hochul May Gut Major Deforestation Bill, Advocates Say”

Biden promised not to drill on federal lands. What does he do? Guess!

Hochul won’t protect the planets lungs it seems.

We can’t vote our way to a sustainable and peaceful earth not when war and unsustainable energy is big business.

Don’t vote! It only encourages them to continue refusing to do the right thing: no more war! Universal and free health care and education! Pollution free environment! If this was a democracy we would be well on our way there. It isn’t!

No way to get this by voting. Indeed by voting it’s even less likely. Ironic!