While supporters say New York City’s right to counsel program needs additional funding to cover all the qualified tenants who need the legal help, they’ve also hailed it a success, and are now pushing to replicate it statewide.

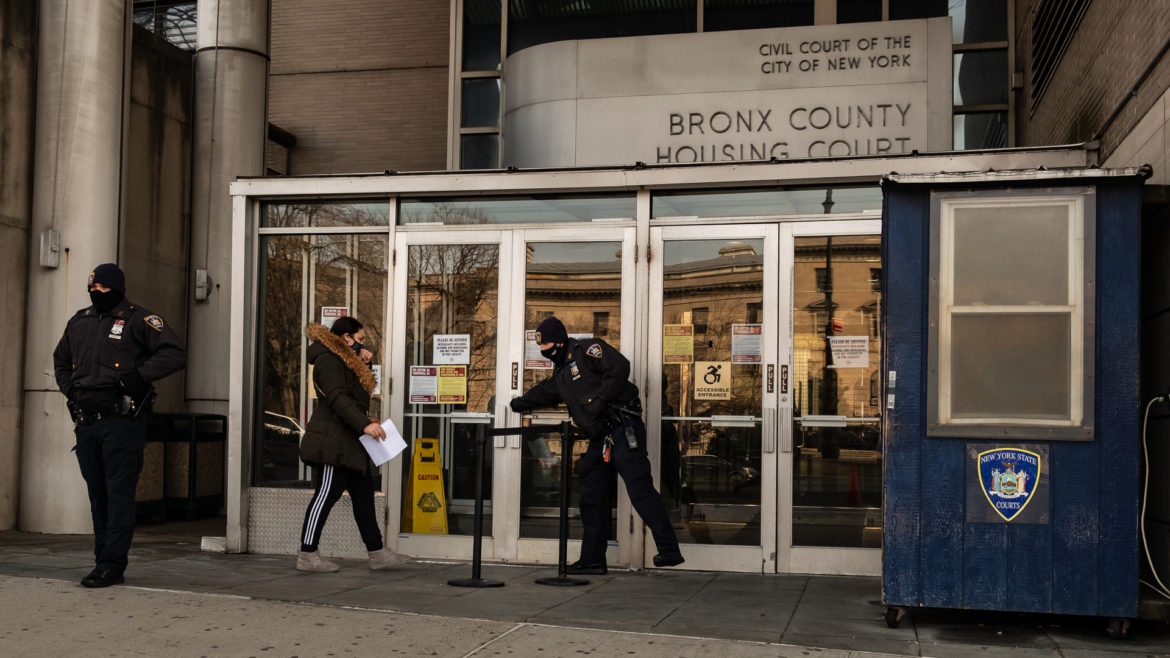

Adi Talwar

Bronx County Housing Court on Jan. 14, 2022, shortly after the state’s eviction moratorium was lifted.In 2017, New York City passed the country’s first right to counsel law, in which low-income tenants facing eviction are eligible for free representation in housing court.

And while supporters say the program needs additional funding to cover all the qualified New Yorkers who need the legal help, they’ve also hailed it a success—saying the vast majority of tenants provided with attorneys were able to remain in their homes—and are now pushing to replicate it statewide.

“Eviction is a tragedy, and a preventable tragedy,” State Sen. Rachel May said at a forum and rally in Albany Wednesday, where member organizations of the Right to Counsel Coalition pushed for a slate of legislation aimed at protecting tenants from eviction.

That includes a bill sponsored by May in the Senate that would establish free legal representation for tenants facing eviction statewide, phased in over five years. While the city’s program has income eligibility requirements—a household of four needs to earn less than $60,000 a year to qualify for free counsel, for example—May’s proposal does not.

“It establishes a right to counsel for all New Yorkers, given that most individuals facing eviction are low-income and given that means- testing will create barriers to counsel for many of the most vulnerable people who most need it,” the text of the legislation reads.

The bill calls for $500 million in funding per year to operate the initiative once it’s fully implemented, which would include establishing a new “office of civil representation” to administer it, as well as invest in legal services and community organizing infrastructure.

The push comes as lawmakers in Albany kick off a new legislative session, where leaders have said they’re looking to pass policies to both spur new housing development and better protect tenants.

“Rents are higher than ever before in New York City,” said Oksana Mironova, a housing policy analyst with the Community Service Society, or CSS (a City Limits’ funder).

The organization released a report this week that found executed evictions and eviction filings in the five boroughs declined by 18 and 22 percent, respectively, since the right to counsel law was implemented—what the group attributes in part to the program “discouraging frivolous filings” from landlords.

But the report notes that evictions will likely continue to raise in 2024, two years after the state’s COVID-19 eviction moratorium was lifted. And many tenants continue to struggle: CSS’ annual survey of nearly 2,000 city residents in 2023 found that one in five Black households and one in four Latino households reported owing back rent last year.

And while the number of actual eviction filings in 2023 was still lower than before the pandemic, the survey found that roughly 15 percent of city households with children reported being threatened with eviction in some way, even in the absence of a formal court filing.

“It’s a perception—so a landlord could say, ‘I’m gonna evict you,’ and then not follow through, but nonetheless, it tracks the broader atmosphere,” Mironova said.

The survey also found that more moderate-income households, defined in the report as equivalent to a family of three earning $47,112 a year, are facing the threat of eviction: 37 percent of those respondents before the pandemic compared to 53 percent last year.

Mironova theorizes that uptick may have been driven by tenants who’d landed cheaper apartment deals during the pandemic, only to see their rents skyrocket now that the market has rebounded.

“We think that some of this could have been mitigated if good cause was on the books,” she added, referring to a bill championed by housing advocates that would give unregulated tenants the right to challenge evictions filed without an established “good cause,” like nonpayment, and rent increases if they’re above a certain threshold.* The legislation has faced significant pushback from property owner groups.

Still, the number of executed evictions in the city last year was down nearly 40 percent compared to 2019, the CSS report found, crediting both right to counsel and the state’s passage that year of a package of laws strengthening rent stabilization rules.

“We’re finding that right to counsel is really effective, but that it’s underfunded and not reaching everybody who’s supposed to have it or everybody who needs it,” said Samuel Stein, a housing policy analyst with CSS.

While the city budget last year included a $20 million boost for lawyers who represent tenants in housing court, legal service providers say funding remains far below what’s required to cover an anticipated 71,400 cases of tenants expected to qualify for the legal help in 2024. As a result, more tenants are heading to court alone, even if they’re eligible for right to counsel.

Attorneys who represent landlords told City Limits they support the mission of the right to counsel law, saying it’s often easier to resolve a case when the tenant involved has legal representation.

In theory, “it should facilitate more settlements and streamline the process and allow the court to function better,” said Deborah Riegel of the firm Rosenberg & Estis, P.C. “Attorneys know the system better than the tenants,” she added. For example, tenant lawyers can help people who owe rent more quickly access emergency assistance, such as via city’s One Shot Deal program.

But underfunding means legal service providers are often saddled with overwhelming caseloads, and “they’re having to turn people down and then those tenants are going into the system without counsel,” Riegel said.

Providers and tenant advocates have pressed the court system to slow the pace of eviction cases so attorneys can keep up. But this is “totally inconsistent with the concept of these being summary proceedings,” intended to be resolved quickly, Riegel argues, and in the case of tenants who owe back rent, can at times allow more debt to accrue.

She cited one case she filed on behalf of a landlord in Brooklyn in September; her next court date, she says, isn’t until March. “It has the feel of an unfunded mandate because it’s so severely under-resourced,” Riegel said.

To reach the reporter behind this story, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org.

*This story has been updated since original publication to provide additional clarification on what the good cause eviction legislation would do.