A recently-opened facility dedicated to “reticketing” has sown confusion, emerging as one of the only options—along with new “waiting areas”—for recently-arrived immigrants forced to leave their shelter placements as the cold sets in.

Emma Whitford

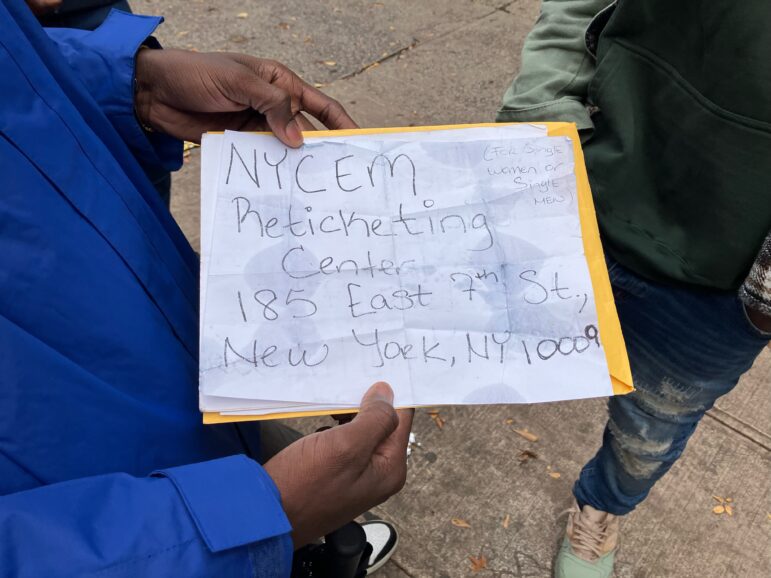

A group of friends from Mauritania show a piece of paper that directed them to the East Village reticketing center on Nov. 1.Lea la versión en español aquí.

Abd Razagh Aw slept outside on Halloween, by the doors of a mosque in the Bronx.

It was his first night sleeping outdoors since arriving in New York City in July, Aw, who is originally from Mauritania, explained in French through a translator. The next day, he went to 185 East 7th St. in the East Village, hoping to secure a bed for the night.

Formerly the St. Brigid School, the boxy building near Tompkins Square Park has been operating since Oct. 21 as a “Reticketing Center,” run by New York City’s Office of Emergency Management (OEM).

Offering recently-arrived immigrants tickets to leave New York City has been standard procedure since families and single adults started arriving in large volumes in early 2022. But this dedicated location has sown confusion, emerging as one of the only options for people forced to leave their shelter placements as the cold sets in.

In Aw’s case, he knew the St. Brigid school was a place to get tickets out of town, but he came anyway in search of shelter. “We came here to see if we could get a hotel, or a room, for free. That’s it,” he said.

There are currently more than 65,000 asylum seekers staying in city-run facilities, according to City Hall, pushing the overall shelter population north of 120,000, compared to about 60,500 in January 2022.

Mayor Eric Adams has issued various directives since July placing limits on how long adults—and, more recently, certain families with children—can stay in a shelter before having to pack up and, if they still need a place to stay, request a new placement.

The administration has said it has no alternative, given space constraints, and has pledged to accompany 60- and 30-day shelter limits with intensified case management to help people get situated in the United States. More than 21,800 notices have been issued to adults so far, according to City Hall.

The St. Brigid reticketing center is meant to serve people after their time has expired, according to an Oct. 27 memo circulated by the Legal Aid Society, relaying information the organization had obtained from the Adams administration.

Emma Whitford

The former St. Brigid School building near Tompkins Square Park has been operating since Oct. 21 as a “Reticketing Center,” run by New York City’s Office of Emergency Management (OEM).Additionally, new facilities without beds, dubbed “waiting areas,” offer a place for adults to wait for a new shelter placement within New York City.

One is located at 4006 Third Ave. in the Bathgate section of the Bronx. City Limits could not confirm by press time if a second facility, at a former church in Astoria, Queens, remained open.

Nearly 8,500 adults have seen their 30- or 60-day notices expire so far, fewer than 20 percent of whom are still in the city’s care, according to the mayor’s office.

Joshua Goldfein, of the Homeless Rights Project with the Legal Aid Society, said that the new system of reticketing and waiting rooms has been incredibly confusing. His organization is currently in court-ordered mediation with the Adams administration, after the mayor renewed a request to suspend shelter rights for adults in early October.

New York City is obligated to provide a shelter bed to anyone in need, at least temporarily—part of a set of rules that grew from a 1981 consent decree in the lawsuit Callahan v. Carey, which pertained to single men.

Legal Aid has maintained that 30- and 60-day notices comply with Callahan so long as a person receives a new placement when their time is up. But this was not happening as recently as a few days ago, according to Goldfein, with people stuck “in chairs all night” at these new facilities.

“If they [the city] want to do it this way, then at a minimum their legal obligation is to offer people a placement at the end of the day if they don’t have anywhere to go,” he said.

According to Legal Aid, people have been receiving shelter placements more efficiently in recent days. The problem was temporarily exacerbated because the fire department shuttered a few shelters over code violations in recent weeks, the organization said. Yet immigrants trying to navigate the system this week were tired, frustrated and confused.

Hugo Báez, 45, stopped by the St. Brigid reticketing center on Wednesday afternoon to see if he could reapply for shelter, in anticipation of his current placement expiring in a few days. But his visit took less than 10 minutes and he left angry and disappointed.

“They are trying to persuade people to get out of New York,” he told City Limits in Spanish. “‘Do you have no other place? Well, I’ll give you tickets to Los Angeles. Or do you want Washington? Or do you want Texas?’ That’s why they send people here.”

A worker at St. Brigid told Báez to calm down, he added, but he wasn’t having it: “He… says to me, ‘Friend, calm down.’ No friend, first [tell me]—is there shelter or no shelter?”

Báez is reluctant to leave the city, having recently started work on his immigration case here. “I’m just doing my paperwork, and you want me to leave New York to start from scratch, no way!” he said.

Jairo, 30, and Gabriel, 24, spent Tuesday night sleeping outside of a gym in Astoria, between motorcycles, before heading to St. Brigid on Wednesday morning.

Once inside, they said, they learned that they could either leave town with help from the city or wait all day for a one-night shelter placement. They declined both, and decided to head to the Bathgate site in the Bronx, on advice from a friend. “It’s all lies,” Gabriel said in Spanish.

Others tried their luck at the Roosevelt Hotel in Manhattan, an intake facility for immigrants in need of shelter who are just arriving in New York City.

Cristian, who asked that his full name be withheld for fear of retaliation, saw his 30-day notice expire on Oct. 30, requiring him to leave his shelter in Midtown Manhattan. He went to the Roosevelt, and was subsequently directed to Bathgate.

Daniel Parra

Cristian outside the Roosevelt Hotel on Nov. 1, where he was given a phosphorescent green paper wristband as he waited for a shelter placement for the third day in a row.Wednesday, he said, was his third consecutive day of cycling back and forth. The routine involved waking up at 4 a.m. to be on time for his job at a flower store in Manhattan. At the end of the day, around 3 p.m., he would return to the Bathgate location to pick up his three backpacks, with all of his clothes and some work tools.

He would then take the train back to the Roosevelt to be processed again, receive a phosphorescent green paper wristband, and go back to Bathgate. “That’s the way it has been for the last few days,” he said in Spanish.

Inadequate translation services have made things worse, according to Jamie Powlovich, executive director for the statewide Coalition for Homeless Youth. She is currently assisting young adults who have immigrated from Africa and speak languages including Wolof or Puular.

“There’s young people who aren’t getting the right information, and others reporting what they are being told… to us and the other volunteers, and it seems like something’s being lost in translation,” she said.

At St. Brigid, people shared slips of paper they received at shelters, some in languages they do not speak, such as English, instructing them to go to the reticketing center.

In a statement, mayoral spokesperson Kayla Mamalek said the Adams administration is doing everything it can to “delay the inevitable” of people sleeping on city streets.

“This includes establishing a reticketing center for migrants,” she said. “Here, the city is redoubling efforts to purchase tickets for migrants to help them take the next steps in their journeys. In addition, we have established waiting areas for those who have left our shelter system and are now asking to return.”

Speaking at a press conference on Tuesday, Mayor Eric Adams described reticketing as a “cost‑effective way of getting a win‑win,” reducing a burden on city taxpayers.

“Some people actually want to go back to their current country of origin because they’ve realized that when you come to New York, you’re not automatically staying in a five‑star hotel,” he told reporters. Others may want to join family elsewhere in the country, he added.

“It is not trying to be misleading,” Adams said. “It’s not trying to be harmful.”

Enderson Leiva, 28, had tried to find a stable job for two months, to no avail. He visited the reticketing center on Wednesday, after his shelter stay expired at the Candler Building in Midtown, and requested a ticket to Miami, where he said family can take him in for a few days.

“They asked me for the name, phone number, and address of the person who would host me and that was it,” he said in Spanish.

But others, like Aw, from Mauritania, want to stay in New York City.

After leaving St. Brigid on Wednesday, Aw explained in French, he ended up staying with two friends in an apartment in Brooklyn. He plans to sleep there again, but is not sure how long he can stay, as he would need money to cover a portion of the rent.

“I’m not happy right now,” he told City Limits Thursday. “I never thought it would be like this. I’m not at ease here.”

Additional reporting by Belle Cushing.

To reach the reporters behind this story, contact Emma@citylimits.org and @Daniel@citylimits.org. To reach the editor, contact Jeanmarie@citylimits.org