There are several key differences between PACT and Hope VI, the now-defunct federal program that facilitated demolition and displacement in Brooklyn decades ago. But, despite contemporary safeguards, advocates say they’ll be keeping a close eye as plans to raze and rebuild the Fulton and Elliott-Chelsea Houses move forward.

For residents at the Fulton and Elliott-Chelsea Houses in Manhattan, neighborhood transformation is considered a norm.

Through their windows, these New York City Housing Authority residents have watched new chapters unfold, like the transformation of an abandoned railway into the elevated High Line park and the old Port Authority into a home for one of the world’s multi-billion dollar companies, Google.

But now, change is on the horizon again—this time, a little too close to home for some tenants. The more than 2,000 apartments that make up the campuses are slated to be torn down and rebuilt, a plan that NYCHA estimates could start as early as the middle of next year.

Under the Permanent Affordability Commitment Together (PACT) program, a local version of the federal Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program, selected NYCHA properties convert from Section 9 public housing to private management with Project-Based Section 8 funding.

By working with private developers, NYCHA hopes to chip away at ballooning capital repair needs—the result of decades of federal disinvestment in public housing.

So far, more than 30,000 apartments have been converted to PACT. However, the Chelsea complex would be the first to undergo demolition. In addition to razing and rebuilding all 2,055 NYCHA units at Fulton and Elliott-Chelsea, the plan will also build 3,500 new mixed-income apartments on the housing authority campuses.

There are tenants who are in favor of the prospective plans, which officials say will replace their current aging homes with brand new, amenity-laden apartments. In June, NYCHA announced that a majority of voting residents opted to have the campus rezoned and rebuilt, a process that could take approximately six years to complete.

But others, like Jackie, who has lived in her Fulton apartment for 21 years, are adamantly opposed to the proposal. Jackie, who asked to be identified by first name only, knows that the demolition of public housing has led to displacement—in the 2000s, in cities like Chicago and NYCHA’s own Prospect Plaza Houses in nearby Brooklyn.

“I read about it all, and that’s the scary part,” she told City Limits.

There are several key differences between PACT and Hope VI, the now-defunct federal program that facilitated demolition at Prospect Plaza and elsewhere decades ago.

Significantly, most of the Chelsea buildings will remain standing and occupied while new towers are constructed on the campus. Developers have also promised a new apartment for each tenant.

RAD, the national model for PACT, was intended to solve for some of the failures of HOPE VI, according to Ed Gramlich, a senior advisor with the National Low Income Housing Coalition. But clear communication with tenants and strong accountability measures for NYCHA and developers will be crucial to its success.

“Time will tell how successful projects like the proposed demolition and rebuilding at the Chelsea-Elliott and Fulton Houses will be,” he said.

Take One: Hope VI

As City Limits reported in July 2001, Prospect Plaza Houses were in fair condition. The development, located in Brooklyn’s Ocean Hill and Brownsville neighborhoods, had four 12- and 15-story buildings housing 1,209 residents as of 1998.

It’s where Leroy Kearse, or “Fatman” to some locals, recalls a “wonderful community.”

Kearse moved into Prospect Plaza Houses when the buildings first opened in 1972. He shared an apartment at 430 Saratoga Ave. with his parents, three brothers and four sisters. “People would look out for one another,” Kearse said.

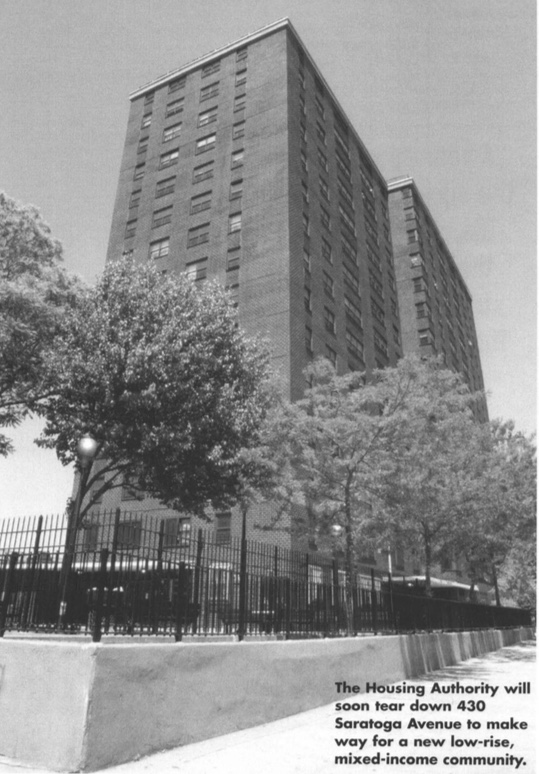

City Limits Archives/Joshua Zuckerman

A photo of 430 Saratoga Ave. before demolition, featured in a 2001 City Limits article about the plans.In 1999, NYCHA moved forward with HOPE VI. Through an application process, housing authorities across the country were asked to select developments they believed were “severely distressed.” The Brooklyn campus was one of 287 demolition grantees between 1996 and 2003, with a $21 million award.

In addition to redeveloping 670 units, NYCHA planned to add mixed-income buildings to the campus. The estimated cost of construction was more than $255 million, according to NYCHA.

Tenants were given options for next steps. They could relocate temporarily during construction to a different NYCHA development in Brooklyn, or they could accept a rental voucher and begin their own search for a privately-owned apartment. Like other properties selected for HOPE VI, Prospect Plaza also offered a homeownership option.

State Assemblymember Latrice Walker, who now represents District 55 which includes her home neighborhood of Brownsville, grew up in Kearse’s building. As she remembers it, there were seven apartments per floor, making it easy to know her neighbors.

But soon before she graduated from high school in 1999, Walker’s mother handed her a letter that would alter life as she knew it. “Complex” was the only word she used to describe the content.

The note laid out plans to reconstruct the property. Her building, 430 Saratoga Ave., would be demolished, while the remaining three would be renovated. But first, all tenants, regardless of their address, would need to temporarily relocate.

They were told they could choose to live in a different NYCHA development and were allowed to say what their preferences were, Walker recalls. “My family chose to go to Glenmore Houses in Brownsville,” she said. “Some people just decided, ‘I’m done with this, I’m moving back to the south and I’m never coming back.’”

This was the case for Kearse’s parents. “My mother stayed at 430 until the last minute,” he said. “When they closed the building my mom didn’t want to go back into New York City housing so she moved to North Carolina.”

In 2005, 430 Saratoga Ave. was torn down. The remaining three buildings were left unoccupied and windowless. “Instead of a place where families and children were laughing and playing, it was like birds and tumbleweed coming down the street,” Walker recalled.

Soon, trouble ensued. NYCHA accused Michaels Development Company, the developer initially selected to carry out the renovation project, of not having enough funds to see it through, while the company accused NYCHA of moving too slowly on its plans, resulting in a lawsuit in 2008.

A new development team was eventually selected, and the remaining three buildings were demolished. Replacements were constructed in three phases between 2014 and 2017.

Adi Talwar

Some of the buildings that replaced the original Prospect Plaza Houses, at the corner of Park Place and Saratoga Avenue in Brooklyn.After over 15 years of living in Glenmore Houses, NYCHA gave Walker’s mother the greenlight to move to one of the new apartments. Walker was relieved, but later found out that she would not be able to return with her. Adding her income would make the mother and daughter ineligible for the unit. She ended up sleeping from couch to couch for a time.

“So basically, it made me homeless but I wanted to make sure my mom got what was deserving of her—all the things that she’d been through,” she said.

To this day, Walker stays in touch with some of her neighbors, whose emails she collected before everyone dispersed. “There was no one-to-one replacement,” she said. “We were made to move into communities we knew nothing about. It broke up families.”

Take Two: RAD/PACT

After HOPE VI ceased in 2010, the federal government introduced the RAD program.

With it, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development hoped to avoid problems that occurred under HOPE VI, pervasive displacement among them.

The U.S. Government and Accountability Office (GAO) reported that in 1999, public housing authority grantees estimated that only 61 percent of original residents in HOPE VI-selected developments would return after reconstruction. In 2003, that estimation dropped to 44 percent, and again in 2006 to 38 percent.

The 2000s saw another NYCHA demolition, at Markham Gardens in Staten Island. Though it was not funded through Hope VI, the vision was similar, according to a 2009 report by the Pratt Center for Community Development.

In its annual plan submitted to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in 2012, NYCHA noted that just 16 of 202 original Markham tenants had moved back into the redeveloped campus. Some tenants reportedly weren’t allowed to return because they had poor credit scores

Under RAD, however, tenants who must relocate for renovations or demolition are given the right to return and, according to a HUD resident rights document, cannot be denied an apartment based on “re-screening, income eligibility or income targeting.”

“So [repeat issues] should be less likely to happen in RAD—if properly overseen and enforced by HUD, which does not always seem to happen,” said Gramlich of the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

RAD policy also states that rent must remain affordable—residents continue paying no more than 30 percent of their income toward rent. And while Prospect Plaza tenants did not have a say in the future of their homes, Fulton and Elliott-Chelsea tenants were asked to vote on the demolition proposal.

NYCHA and Essence Development and Related Companies, the developers tapped for the demolition in Chelsea, say that residents will not be displaced.

Though zoning approvals are still needed, the developers are planning what they call a “build first” model. According to Essence, an estimated 94 percent of residents will remain in their current apartments until the new construction is complete.

Tenants living in two towers—Fulton 11, with 35 households, and Chelsea Addition, with 85 households—may be temporarily relocated during construction, either to vacant apartments within the campus, or other apartments within the Chelsea neighborhood.

According to NYCHA, these buildings were chosen because they are small, and will minimize relocations.

“Fear mongering the narrative about HOPE VI is misguided and unjustified, and only serves to undermine the voices of NYCHA residents who have made clear they no longer want to wait for federal funding for capital improvements,” a NYCHA spokesperson wrote.

Jamar Adams, the founder and managing principal of Essence, told City Limits in a statement that concerns are understandable, but claimed that most residents are excited about the project.

“With change, especially regarding residents’ homes, there will of course be some mixed emotions,” he wrote. “But the overwhelming response we’ve received is that of excitement and anticipation, and we will continue to work with all residents to ensure their voices are heard throughout this entire process.”

Among that group is Yu Story, a 77-year-old resident at Chelsea Addition, a senior building, and one of two properties that tenants may have to vacate during construction. She said her only issue with the proposal is that the plans, which she calls her “American dream,” are not happening soon enough.

“There’s rats, water pipe [issues], the elevator stops or sometimes it will take a long time,” Story said. “I’m starting to pack right now.”

But Anna Luft, a project director for the public housing justice project at the New York Legal Assistance Group (NYLAG), told City Limits that she has seen some pitfalls with RAD in her experience with tenants.

“We are frequently seeing cases where tenants or family members are falling through the cracks during the conversion process and landing in housing court,” Luft said.

Last year, Human Rights Watch found that 50 tenants were evicted from Ocean Bay, the first development in NYCHA to convert under RAD. NYCHA later said those claims were “unsubstantiated.”

“It makes me very nervous for the residents who will be displaced during FEC [Fulton and Elliott-Chelsea] demolition,” said Luft.

Adi Talwar

Tenants protest NYCHA’s demolition plans outside the Fulton Community Center in September.Luft also charged that the developers are not off to a good start, because the voting process for residents to opt into the demolition plan was not adequately transparent. The survey asked tenants to select between rehabilitating existing units and two “new construction” options—but did not explicitly note that the latter would involve tearing the current buildings down.

“I think the lack of transparency is feeding the totally understandable concerns and distrust of the residents at FEC and in developments across the city,” she added.

Regardless of RAD’s safeguards, some level of disruption seems inevitable for NYCHA residents in Chelsea.

Jose Huertas, a Harlem resident, took the stage at a September Community Board 4 meeting, where Fulton and Elliott-Chelsea tenants packed the room. His 96-year-old aunt, or “Titi” as he calls her, has lived at the Chelsea Houses for 60 years.

Titi lost two children during the COVID-19 pandemic, he said, and further change could cause her stress.

“While minor systemic repairs are welcome, the proposed project for her home would be devastating,” Huertas told the crowd. “My Titi is 96 years old. She’s an active, bilingual Puerto Rican grandmother seeking peace with no devastating disruptions.”

To reach the editor behind this story, contact emma@citylimits.org. To reach the reporter, contact tatyana@citylimits.org.

3 thoughts on “As Chelsea Demo Plans Move Ahead, A Look Back to NYCHA’s Brooklyn Razing”

Why does Ms Turner state, without further explanation, that there is a federal government obligation to provide housing? Where is this obligation written in the Constitution?

In fact, the City should be responsible for housing it’s citizens. And Bill De Blasio should be in prison for feeding child lead paint.

All of the smaller NYCHA buildings should either be torn down and redeveloped with more units or expanded with more units. Grounds should be infilled wherever possible. Commercial units should be placed at the street level along major corridors in some modified or newer buildings.

Prospect Plaza’s redevelopment was poorly planned. It could have brought so many more needed units. The plans for Fulton and Chelsea are much better in comparison.

Housing for city residents should fall under the purview of the city. Bill De Blasio ought to be imprisoned for feeding lead paint to children.