A fight over whether to demolish and rebuild apartments at the Chelsea-Elliott and Fulton Houses in lower Manhattan echoes a larger debate over how NYCHA should raise funds for its deteriorating housing stock, and how much of a say tenants will have in those plans.

City Limits / Harry DiPrinzio

NYCHA’s Fulton Houses in Manhattan.Celines Miranda, a resident at NYCHA’s Chelsea-Elliott Houses, likens a part of the Lower Manhattan campus to a forest. “Between 25th and 26th street is beautiful—there’s a lot of open space and greenery,” she said.

During her usual strolls, Miranda said she sees children playing on the playground, families celebrating birthday parties and men sitting around a table as they wait their turn in a game of dominoes. Above them, she said, are tall trees protecting them from the blazing sun.

So when Miranda filled out an online survey this spring asking her to choose between demolishing and rebuilding Chelsea-Elliott Houses or rehabbing the development’s existing apartments, she chose the option she felt would best preserve and protect her community.

“I voted for rehab,” Miranda said.

Last month, NYCHA announced that more than half of participating voters at Chelsea-Elliott and the nearby Fulton Houses were in favor of demolition and reconstruction of their homes—paving the way to tear down and replace all 2,055 apartments at the lower Manhattan campuses, where developers will also build 3,500 mixed-income apartments on housing authority land, 2,625 of which be market-rate rentals.

NYCHA officials said the vote came after “an unprecedented resident engagement effort,” and that the rebuild plan will allow tenants to swap their current apartments for new, modern and amenity-filled units. The NYCHA developments covered by the plan—which includes the Fulton, Elliott, Chelsea, and Chelsea Addition campuses—are in need of an estimated $366 million in repairs.

And that’s just a fraction of what NYCHA says it needs to address problems system-wide: on Wednesday, the housing authority projected a new capital investment need of $78.3 billion for all of its 328 developments—a dramatic 73 percent increase since its last physical needs assessment in 2017, when the estimated price tag was $45.2 billion.

NYCHA CEO Lisa Bova-Hiatt said the new assessment shows the “tremendous magnitude” of the needs and challenges NYCHA faces, caused by years of disinvestment from all levels of government.

Over the last few years, the housing authority has pursued several plans to raise money to deal with its deteriorating housing stock, including the formation of the Preservation Trust and a separate initiative, the Permanent Affordability Commitment Together (PACT) program.

“Improving conditions for residents remains our top priority, and we continue to utilize every available tool, including PACT and the Public Housing Preservation Trust, to reduce this gap and bring investment into our properties,” Bova-Hiatt said in a statement Wednesday.

NYCHA estimates that $38 billion of its current repair needs can be resolved through the PACT and Preservation Trust programs.

Beginning this summer, tenants at selected NYCHA campuses will be asked to vote on whether they want their development to remain as is, to join the Trust or convert to PACT. Under PACT, private management companies are put in charge of operations at a given development and apartments are shifted to the federal Section 8 program, allowing NYCHA to unlock additional revenue sources it can’t access under the traditional Section 9 public housing model.

But tenants have raised concerns about how democratic that voting process will be, worries that have similarly dominated recent discussions on the future of the Chelsea-Elliott and Fulton Houses.

In the weeks since NYCHA announced the results of the spring vote there, tenants and advocates have spoken out against the demolition plan, saying some residents weren’t fully informed on all the details and may not have been aware of the significance of the survey.

For Miranda, her only regret was clicking any option at all.

“I didn’t know any better,” Miranda said. “I don’t want them here because I’m finding out more stuff.”

“Them” refers to Essence Development and Related Companies, a resident-selected development team whose names residents grew familiar with over the past several years. In 2019, the developers were introduced to the scene when the idea of remodeling and partially demolishing the downtown developments first surfaced.

A Chelsea Working Group was formed consisting of leaders ranging from tenant association presidents to U.S. Representatives. Residents supported the idea of unit upgrades but were apprehensive about demolition—eventually striking down the project.

Two years later, in 2021, plans for demolition were resurrected. Essence Development and Related Companies were chosen to rehabilitate the Chelsea, Chelsea Addition, Elliott and Fulton Houses under the PACT program.

In a statement Wednesday, ahead of a public hearing to be held on NYCHA’s annual financial plan, the Legal Aid Society and Community Service Society (a City Limits’ funder) issued a statement denouncing the recent vote, saying the process “is in violation of nearly every principle established by the Chelsea Working Group,” and called NYCHA’s claim that the vote was led by residents “misleading.”

“This plan is unequivocally not resident-led, and is guaranteed to uproot the lives of thousands of vulnerable New Yorkers, many of whom have resided in the [Fulton and Elliot-Chelsea] community for generations,” said Lucy Newman, staff attorney with the Civil Law Reform Unit at The Legal Aid Society.

The two organizations took particular issue with the “build first” approach planned by NYCHA, Essence and Related—what the housing authority says will minimize disruptions during the transitional period. An estimated 94 percent of households would stay in their apartments while construction takes place, while the other 6 percent, who currently live in Fulton 11 and Chelsea Addition, would be briefly relocated to another building on campus or within Chelsea Houses, officials say.

“Because the demolition of existing units will commence before the construction of all needed new units is completed, including a building occupied entirely by seniors, many households are facing displacement for an undoubtedly lengthy period of time,” Legal Aid and CSS said in their press release condemning the plan. “Historically, when people are relocated in this way it is highly likely that they will not return to their homes, resulting in permanent displacement.”

That’s also a concern of some tenants, who have organized protests in the wake of the voting results announcement, where they wrote on poster boards, shouted into bullhorns and even banged their hands on drums to get their message across: no demolition.

“I just feel like a lot of people are going to get evicted—the most vulnerable crowd because Section 9 was made to protect the most vulnerable—the low income, the disabled and the senior citizens,” Miranda said. “The people who did not vote are speaking loud and clear.”

Marquis Jenkins, a founding member of a group called Residents to Preserve Public Housing, called the demolition and reconstruction a “devious plan to tear down public housing.”

“And we are here to block that plan,” said Jenkins. “What you do in public housing will impact everything surrounding public housing—our neighbors, our businesses and our services will be changed by what you do to the public housing residents.”

Residents also critiqued the voting process.

“Why couldn’t you send everybody a certified letter?” said Jackie, a resident at Fulton Houses who asked to be identified by first name only. “You’re putting plastic bags with booklets on our door knob which some people could take or some of us just didn’t get.”

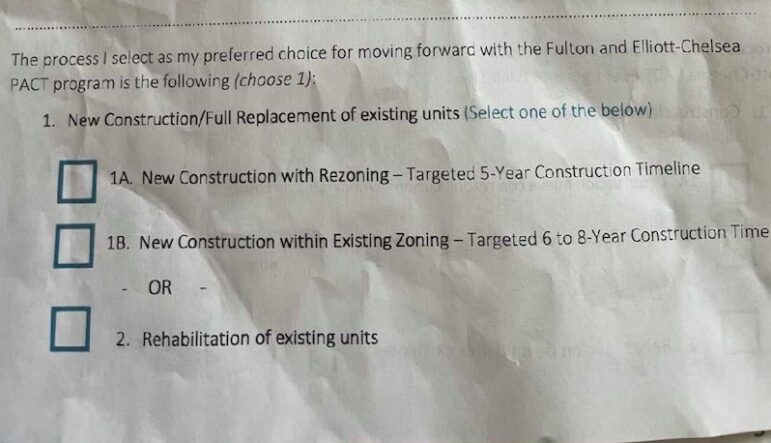

The survey, an image of which was shared with City Limits, asked tenants to select from one of three options: “New Construction With Rezoning,” which would take an estimated five years to complete, “New Construction Within Existing Zoning,” which would take six to eight years to finish, or “Rehabilitation of Existing Units.”

Screenshot

A portion of the survey distributed to tenants at the Fulton and Chelsea-Elliott Houses.The wording of those choices, Legal Aid and CSS complained, “[obscured] the fact that two of the survey options required complete demolition and were totally silent on the development of 2,500 market-rate apartments.”

“I did not fill it out,” Jackie said, of the survey NYCHA distributed to tenants. “These buildings were meant to last a long time.”

According to a NYCHA spokesperson, the housing authority, Essence Development and Related Companies held 35 information sessions about the vote. Over the course of 60 days, surveys and information packets were distributed at meetings, online and to every apartment so that eligible tenants 18 years and older could have their say.

Votes from the survey were analyzed and verified by the Citizens Housing and Planning Council (CHPC), an nonprofit housing organization.

Howard Slatikin, CHPC’s executive director, said it was “incredibly powerful” to see the role NYCHA residents had in making the decision for the upcoming project.

“Essence Development, NYCHA, and the resident leaders at Fulton and Elliott-Chelsea have achieved exceptionally high resident participation in this survey, ensuring that residents have an active role in shaping the future of their homes,” Slatikin wrote in a statement. “This process highlights the importance of transparency and partnership with NYCHA residents in navigating challenging decisions to improve their quality of life.”

The new buildings that will replace the current ones are slated to be mixed-use high rise buildings with health clinics, grocery stores, on-site security and rooftop space.

Units are planned to include dishwashers, washers and dryers as well as resident-controlled heating and cooling systems. Construction, coupled with approval for taller buildings, yields an approximate six year completion time, according to NYCHA.

Officials stress that tenants will maintain the same rights as they have now: Rent will be maintained at 30 percent of adjusted household income, heads of households can continue to be able to add relatives to their household composition and lease renewals will be processed automatically.

Miguel Acevedo, a tenant association president at Fulton Houses, is among those in support of the transformational plan.

“Public housing is in one of the worst conditions it has been in so many years,” Acevedo told fellow residents in a virtual meeting held by the Midtown South Community Council earlier this month. “If we don’t find the right plan with real money—not money people are telling you they can save through Section 9—we’re going to lose more stock in public housing.”

In a joint statement Wednesday, Acevedo and Chelsea-Elliot Tenant Association President Darlene Waters defended the vote, calling CSS and Legal Aid “outside groups” and calling their concerns about the process “outright lies.”

“The tenants we represent overwhelmingly chose new construction at Fulton-Chelsea Houses because we deserve new, safe, healthy homes. Anyone who says otherwise, stands against the tenants, tenant leadership, and the elected officials who represent our complex,” the pair said.*

But for residents like Jackie, the process means more than revitalization.

“Fulton is not a home, it’s a feeling,” she said. “We all look out for each other’s kids, we all look out for our neighbors, we became a family and we have a bond.”

Miranda, who takes care of her 73-year-old mother, said when the two of them go outside, her mother tends to get disoriented—confused about which direction to go.

“But once she’s here in her community, in her home, she knows where she’s at,” Miranda said. “So what’s going to happen if they demolish these buildings and give us a new building? She’s going to be completely lost.”

*This story was updated since original publication to include additional comment from the tenant association presidents of the Chelsea-Elliott and Fulton Houses.

One thought on “Questions Arise About Voting Process in NYCHA Demo Plan, as Public Housing’s Repair Bill Climbs to $78 Billion”

Nycha is full of lies and needs to be sued which I am in the process of getting legal representation to do so. They sold my building in 2018 with the rad conversion/pact nonsense with cross bronx Preservation to C&C management. Nycha FAILED to fix issues to recall their Sec 8 dept to have a reinspection. Then C& C management furthered the mess ups & possibly committed a federal crime with the rent assistance help so they also are being taken to court as my rent is suppose to be only 30% of income yet Feb 2021 mind you rent was in a freeze due to covid19 until JUNE 2021.. but in feb 2021 C&C stopped charging me the 30% & put it to market rate of $2400-2500. This is a sham the bs of remodeling after selling privately.. oh and guess what? C&C don’t do repairs & leave a repair half done now for over a year.. elevators are out every wk .. so tell me how it’s improving our quality of life?