So far this year, city marshals have executed at least 1,527 residential evictions, according to statistics maintained by the Department of Investigation (DOI). The true number of legal evictions is likely higher because DOI updates its database only after a marshal reports an eviction, which can take days or weeks.

David Brand

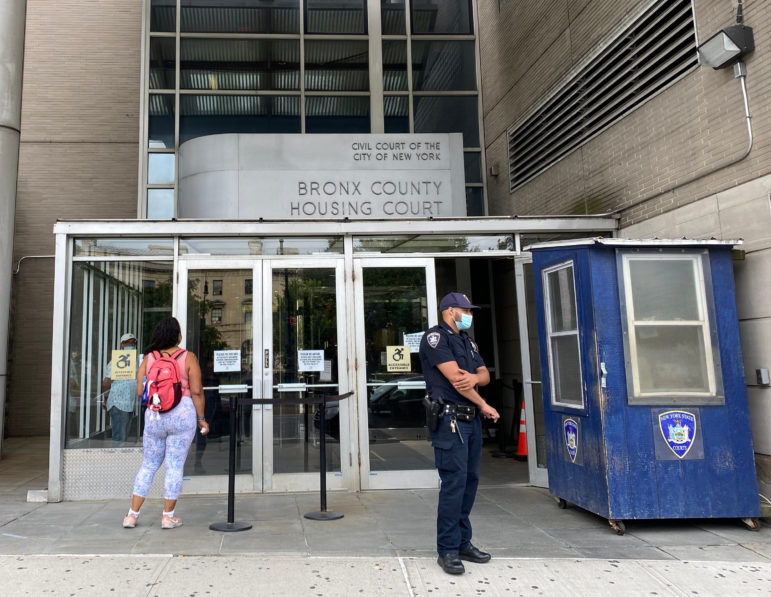

Bronx Housing Court on Aug. 16, days after the Supreme Court struck down a central part of New York’s COVID eviction moratorium.The number of legal evictions in New York City grew each month in the first half of 2022 as rents skyrocketed and pandemic tenant protections began to diminish, city data shows.

So far this year, city marshals have executed at least 1,527 residential evictions, according to statistics maintained by the Department of Investigation (DOI). The true number of legal evictions is likely higher because DOI updates its database only after a marshal reports an eviction, which can take days or weeks.

A state ban on most evictions ended Jan. 15, but the expiration did not initiate a sudden spike in legal removals, with various requirements prolonging the process so long as tenants respond to notices and visit Housing Court. The steady increase is nevertheless clear from the data maintained by DOI. Meanwhile, a mounting number of eviction filings suggests that removals could increase exponentially in the coming months.

At least 315 households were legally evicted in June, up from 103 in January. Another 214 households were evicted in the first three weeks of July, according to the incomplete DOI data set. The rise in evictions has coincided with an increase in the number of people entering city homeless shelters, though the city’s Department of Social Services (DSS) estimates that only about 1 percent of people entering shelters between January and May became homeless as a result of an eviction. Prior to the pandemic, from March 2019 to February 2020, about 10 percent of shelter entrants became homeless following an eviction, DSS said.

“This is exactly what we expected when the moratorium ended and that's an increase in evictions,” said Judith Goldiner, a supervising attorney at the Legal Aid Society.

The so-called “eviction moratorium,” enacted via a series of executive orders and state laws at the start of the COVID-19 crisis, prevented landlords from ejecting tenants for not paying rent from March 15, 2020, the day of the first freeze order, to Jan. 15 of this year. Tenants could still be kicked out of their apartments for breaking the rules of their lease or creating unsafe conditions for other residents.

The end of the broader eviction ban allowed landlords to proceed with nonpayment and so-called “no defense” holdover cases, in which property owners go to court to remove a tenant who does not have a current lease. Goldiner said the state legislature’s failure to pass a bill that would give tenants in non-rent regulated apartments the right to a lease renewal and the ability to challenge large increases—dubbed the “Good Cause” eviction bill—has led to more people losing their homes amid an historic surge in monthly rents. Dramatic hikes in non-stabilized apartments have become the norm across New York City, with tenants who cannot pay up forced to find other accommodations.

Goldiner said many tenants behind on rent and facing removal have chosen to self-evict—a number that is not reflected in the city data.

“People are living in apartments they can’t afford and they haven’t gotten their job back,’” she said. “We hear, ‘I didn’t want to wait for the marshal to come’ so they take their kids and get their stuff out.”

Statistics maintained by the state court system seem to bear that out. Judges in New York City have issued 5,099 warrants of eviction this year as of July 25, according to a court system tracker. The DOI data shows that less than a third of the warrants have resulted in a marshal changing the apartment locks or removing tenants, suggesting that many cases get resolved before an eviction, said Justin La Mort, a supervising attorney with the organization Mobilization for Justice.

Tenants may leave, reach a resolution with the property owner or go back to court to request a stay on the eviction, La Mort said. But more evictions are no doubt on the way, he added.

“Instead of seeing one tsunami you’re seeing a large rolling wave, and the tide is rising,” La Mort said. “The more cases being heard in court, the more people are going to be evicted.”

The number of eviction filings have begun to approach pre-pandemic levels, according to the state court data. There have been 54,208 eviction cases filed in New York City so far this year, compared to 45,037 all of last year and about 78,000 in 2020. There were nearly 180,000 eviction filings in 2019.

Despite the uptick, the number of legal evictions so far this year pales in comparison to years prior to the pandemic. In the 28 months since March 13, 2020, marshals have executed 1,696 evictions, according to the DOI data. That’s roughly the equivalent of five weeks in 2019, when there were around 17,000 legal evictions.

Landlord attorney Nativ Winiarsky, a partner in the firm Kucker Marino Winiarsky & Bittens, LLP, called the 2022 total “infinitesimal.”

The statistics, he said, “reflect the fact that landlords are still facing a very difficult time recovering units from tenants who have defaulted on their rental obligations.”

He said he expects the amount of evictions to continue to rise, but Housing Court delays and opportunities for tenant relief means “they will not in any way reach the pre-pandemic numbers.”

Some safeguards enacted during the pandemic do remain in place for tenants to stall or halt the eviction process, including a right to an attorney for the lowest-income renters and a state rental assistance program that prohibits landlords who receive the funding from evicting their tenant applicant for a year in most cases.

Fordham Heights nursing home aide Ruth Ortiz worries none of those will be enough to prevent her from losing her apartment.

Ortiz, 51, first talked with City Limits in August 2021 outside Bronx Housing Court after she arrived to respond to the nonpayment notice she received. At the time, she owed $2,973.33—the equivalent of three months and change, court records show.

Ortiz said Monday that she earns too much to qualify for a free lawyer—and even if she did, with filings quickly mounting, organizations providing that representation say they do not have the capacity to take on every case.

Ortiz said she successfully applied for the state’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP), allowing her landlord to receive a payment on her behalf in September 2021. But since then, she said, she has fallen even further behind on her rent because her work hours and income were cut nearly in half.

When City Limits contacted her Monday, she said she was home with COVID-19 and experiencing a fever and chest pain. She said she applied for ERAP again in May but fears the relief fund, replenished in the most recent state budget and once again processing applications, will run dry, leaving her unable to reimburse her landlord.

The landlord—a limited liability corporation named after her building address—and her management company did not respond to emails and phone calls seeking comment.

“I don’t know what I’m going to do, to be honest with you,” Ortiz said. “I’m going to have to pick up my luggage and where I am going to go, under a bridge?”

6 thoughts on “NYC Evictions Have Increased Every Month This Year”

Still a vanishingly small number for a city with millions of housing units.

Tell those families who have been displaced that they’re vanishingly small.

You should write about smart a** tenant, who capable of is paying rent, but do not pay for almost 3 years. Simply because they know how to trick the system. Cannot evict this guy since October 2019. He occupies a luxury 2 bedroom/2 bathroom condominium apartment with an underground parking. Did not pay a penny for 30+ months.

There are employees and retirees of Housing Court buying condos and houses in Queens who own coops in Manhattan while poorer tenants are being threatened with eviction. Don’t leave if you only have 1 place to live.

THE CITY STOPPED BUILDING LOW INCOME HOUSING 40 YEARS AGO!!

SRO “LOW INCOME HOUSING” STOPPED 60 YEARS AGO!!

EVERYONE HATTED “PROJECTS”.

AFFORDABLE HOUSING IS NOT LOW INCOME HOUSING!!!!!!!

WAKE UP!!!

GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS: CITY, STATE, FEDERAL:

POOR PEOPLE IN NYC NEED LOW INCOME “PROJECTS” AND “SROS”

TO END HOMELESSNESS!!

FAKE SECTION 8 VOUCHERS THAT DO NOT EXIST AND FAKE

“AFFORDABLE HOUSING” DOES NOT SOLVE THE LOW INCOME

HOUSING PROBLEM IN AMERICA!!!

Funny , How come this article doesn’t talk about landlords who haven’t gotten a penny from. Tenant or Erap for 2 1/2 years that’s weird .