For the first time in nearly two years, New York’s expansive COVID-related eviction protections have come to an end for tenants who owe back rent. Landlords are rejoicing, renters are feeling the heat and city officials are bracing for impact.

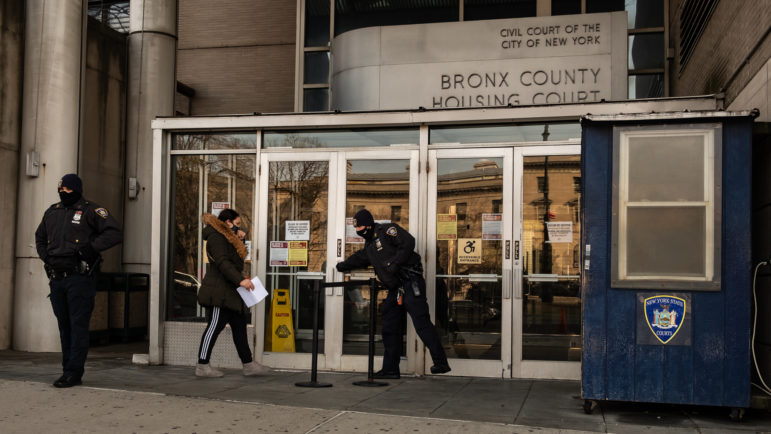

Adi Talwar

A short-lived line formed outside Bronx County Housing Court around 11 a.m. Tuesday.For the first time in nearly two years, New York’s expansive COVID-related eviction protections have come to an end for tenants who owe back rent.

Landlords are rejoicing, renters are feeling the heat and city officials are bracing for impact. Over at Bronx Housing Court, laid-off teacher Alex Gutierrez just wants to hold onto his apartment.

Gutierrez, 30, said he has lived his whole life inside a six-story building on Walton Avenue, near Yankee Stadium, and walked nine blocks to the courthouse Tuesday to respond to an eviction notice he received last week. He was one of a few dozen tenants and property owners who visited the Grand Concourse courthouse on the first business day since the state’s broad eviction freeze ended on Jan. 15.

His landlord, a limited corporation owned by Ved Parkash—a fixture of the public advocate’s Worst Landlords List—had sued to evict him over $3,500 in unpaid rent. Gutierrez said he struggled to keep up with his monthly payments after losing his job as a physical education teacher because of a vaccine mandate, but has made partial payments. He said he plans to come up with the money for the full amount and hopes to soon resume his teaching job after getting a COVID vaccine next week.

“I thought he’d be understanding,” Gutierrez said as he stood in the frigid breeze, saying that Parkash has let building conditions deteriorate in recent years. “They’re not going to fix nothing, but they’ll try to evict you the moment you’re late.”

A representative for Parkash said the eviction notice was standard procedure. “We tell everyone to go answer the paperwork and [New York City will] give them free legal assistance,” the person said before hanging up the phone.

Similar dramas unfolded across New York Tuesday morning—a precursor of an uncertain future for tenants and landlords alike.

By 10:30 a.m., eight people stood inside Bronx Housing Court and waited to submit documents to a court clerk behind a partition. Some were landlords filing for eviction, while others were tenants responding to notices. One landlord was submitting paperwork to prove he made court-ordered building repairs. The queue gradually grew over the next hour, with a handful of visitors forced to stand just outside the entrance.

Attorneys and court officers said the turnout appeared to mirror recent weeks at the courthouse—a far cry from the lines of respondents who wrapped around the block on a daily basis prior to the pandemic.

“The difference is it used to be thousands, now it’s hundreds,” said a court officer working near the building entrance. “It’ll pick up,” another added.

Jordan Dewbre, a housing attorney at the organization BronxWorks, agreed. He works next door to the housing court building and said the anticipated wave of eviction filings has yet to crest in The Bronx.

“It’s been less of a mad rush on Housing Court than I expected,” Dewbre said. “It’s not a line around the block which we were thinking it might be.”

Nevertheless, he said, several tenants showed up at the BronxWorks offices or called him to request assistance, with many seemingly motivated by the end of the eviction freeze.

“A lot of folks are coming in terrified that they’re going to be out on the streets today or tomorrow now that the moratorium has ended,” Dewbre said.

That isn’t the case for the vast majority of renters at risk of eviction, however. Several protections still exist for tenants who respond to the notices they receive and who apply for state or city assistance, Dewbre said. Very low-income New Yorkers earning less than 200 percent of the federal poverty line (about $23,000 for an individual or $49,000 for a family of four) have the right to full representation in housing court under city law. All others have access to at least some legal assistance.

Tenants can guard against eviction by proving in court that they experienced financial hardship and could not pay rent as a result of the pandemic under the state’s Tenant Safe Harbor. That law could prevent eviction for unpaid rent between March 16, 2020 and Jan. 15, 2022, but it does not protect tenants from money judgments. Renters can also apply for cash grants known as one-shot deals from the city or attempt to negotiate with their landlords outside the courtroom.

And then there’s New York’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP), which has issued payments to landlords on behalf of about 100,000 households since June 2021. State officials say the tapped-out fund will not be able to cover rent for about another 85,000 applicants without a federal cash infusion, but households that apply for ERAP can effectively delay eviction proceedings until the Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance (OTDA) determines their eligibility for the program, the state’s chief administrative judge wrote in a memo Sunday.

Another round of federal money—still unclear how much—will replenish the fund in April and could cover back rent for applicants yet to benefit from the program. More state help could be on the way, too: Later Tuesday, Gov. Kathy Hochul unveiled an executive budget that includes $2 billion of additional pandemic-related aid. A portion of the money could fund “struggling, small landlords and their tenants,” she said.

Still, an untold number of New Yorkers could fall through the cracks.

One woman at Bronx Housing Court said she showed up to answer an eviction notice. She said in Spanish that she owed $43,000 in arrears after withholding payment because her landlord did not make necessary repairs on the building. Another man said he could not keep up with his rent payments because he lost most of his work selling food on the street during the pandemic. Both said they would likely have to enter a homeless shelter if they lost their apartments.

There are now more than 220,000 eviction cases on the books across New York City, though many of those have been resolved outside of the court system, said Office of Court Administration (OCA) spokesperson Lucian Chalfen. OCA will have a more accurate view of the number of active cases once they are added to judges’ calendars and updated, he added.

Across the state, nearly 600,000 households owe back rent, according to an analysis by the policy group National Equity Atlas. Recent reports by the Community Service Society of New York (a City Limits funder) and the Robin Hood Foundation found that one in four low-income tenants are behind on their rent, with Black and Latino women at the highest risk of eviction.

“Make no mistake: a wave of evictions is coming that will put hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers at risk,” said Robin Hood CEO Richard Buery. His organization has advocated for increasing the value of city rental assistance vouchers, removing bureaucratic obligations and expanding access to the CityFHEPS program.

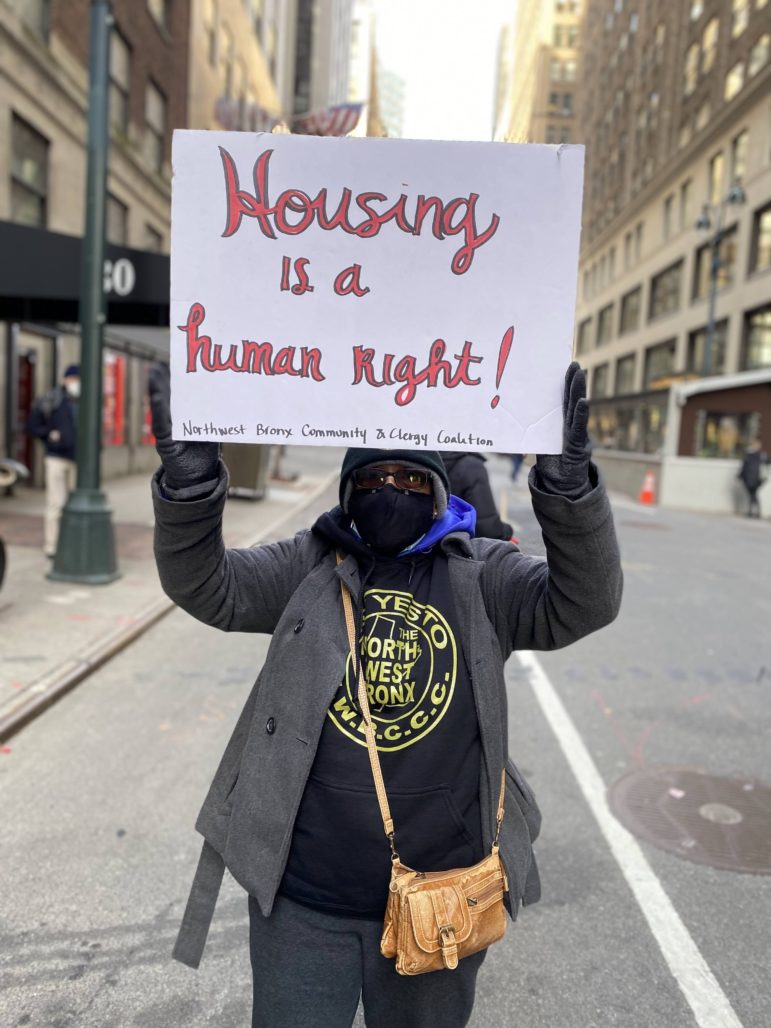

Some have called for more drastic measures. More than 100 tenants and their advocates marched through the streets of Manhattan to Hochul’s Midtown office Friday to demand another extension of the eviction moratorium. Hochul and state lawmakers did not take them up on that recommendation.

Landlords and their representatives at Bronx Housing Court said they were eager to move on from the COVID-related eviction freeze and start getting their money, or ejecting the tenants who have failed to pay for their homes.

“It’s about time,” said Garnet Samuels, a Queens homeowner who helps landlords navigate the eviction process. “This has been a lot of strain on landlords and it’s about fairness.”

Samuels said he planned to evict the tenants renting a unit in his two-family home because they have not paid rent in more than a year, he said. He showed off a stack of papers and said he was assisting five property owners in filing their own eviction petitions Tuesday.

Another landlord declined to give his name but showed the notice he planned to file against his tenants. He said he has been waiting a few months to start the eviction process because the tenants have declined to apply for ERAP funds.

“This moratorium has to end sometime,” he said. “We have mortgages to pay.”

One thought on “A Trickle of Tenants at Bronx Housing Court as Eviction Moratorium Ends”

Good afternoon my name is April McCormick I need help paying my back rent. I applied for ERAP but they told my last month when I called that they was not going to help me since I live in the projects. In 3020 I was paying 999.99 for rent as a teacher aid got sick and was out of work ended up getting hurt on the Jones’s getting 300 dollars every two weeks for workers compensation. Went back to work online. Went back to school July 8th of 2031 and got injured again and get 400 every two weeks. Been out of work every since. My number is 929-541-0380. Just trying to get help.