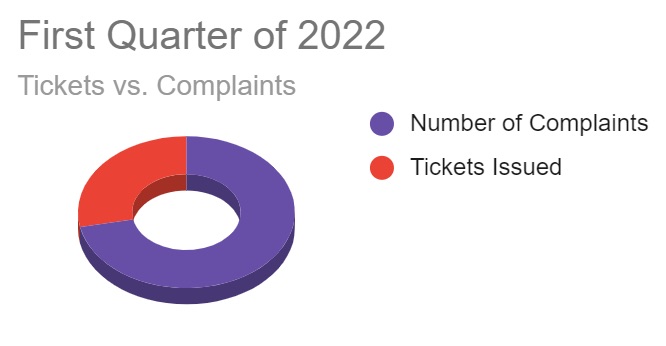

City agencies, including the NYPD, issued 570 tickets to street vendors during the first three months of 2022, exceeding the number of fines during the same period in 2019: 366.

Adi Talwar

A street vendor in the Bronx in winter of 2021.Lea la versión en español aquí

Last weekend, the Street Vendor Project posted footage on Twitter of the arrest of a street vendor selling mangoes, melons, and other fruits in the subway, sparking anger on social media and public condemnation from several lawmakers. The NYPD patrols and enforces rules against vendors in the city’s subways, since public vending is against the law in the transit system.

The arrest took place on April 29, so by the time the video went viral María had already been held for a few hours, allegedly searched for drugs and weapons, and released. She received a citation for unauthorized commercial activity.

Mayor Eric Adams’ deployment of more police to subway stations comes as enforcement against street vendors has stepped up again after a lull in 2020, and the first quarter numbers for 2022 continued apace with the higher, pre-pandemic levels. The two city agencies in charge of vending enforcement, the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP) and the NYPD, issued more fines during the first quarter of 2022, 570, than during the same period in 2019: 366.

Moreover, in the first quarter of this year, as many fines were issued as during the most fined quarter in 2019 (571 issued in the second quarter of 2019). DCWP issued 348 vending fines during the first three months of 2021 whereas the NYPD issued 222 fines, according to the police department’s quarterly reports. The vast majority of 2022’s fines—319—were issued to mobile food vendors such as María, and 29 to general vendors.

When asked about the viral video of María’s arrest, Mayor Adams defended the incident as part of his ongoing effort to enforce the rules of the subway system. “If we follow the rules, we won’t have these incidents. And we’re going to evaluate the interaction with the police and always find better ways to do so,” he said during a press briefing earlier this week, arguing that letting one rule slide can lead to more egregious violations, a refrain he’s made previously. “Next day is propane tanks being on the subway system, next day is barbecuing on the subway system. You just can’t do that.”

READ MORE: Some NYC Vendors Are Using Excluded Workers Fund Aid to Cover City Fines

When it comes to enforcement above ground, it has been more than a year since the DCWP—formerly known as the Department of Consumer Affairs (DCA)—took over street vendor inspection functions previously performed by the NYPD. Former Mayor Bill de Blasio enacted that change at the start of 2021, part of his effort to trim the police department’s budget and respond to complaints by advocates and vendors, many of whom are immigrants or people of color, who said they’ve been subject to years of overly-punitive enforcement from officers.

But the change hasn’t meant less enforcement. Last year, the city issued 1,621 tickets to vendors, outpacing the 1,609 civil and criminal summons issued in 2019, despite the fact that DCWP’s active enforcement in 2021 only began June 1 (the agency spent the first few months of last year doing vendor outreach and education instead).

According to DCWP, the percentage of joint work conducted with the police department varies on a weekly basis; recently, it’s been approximately 15 percent of vendor enforcement, the agency reported. A police spokesman said that “there have been multi-agency joint operations (NYPD, Dept. of Consumer and Worker Protection, and Parks Department) in and around the Broadway Junction subway station [where María was filmed] prompted by numerous complaints from the MTA station manager.”

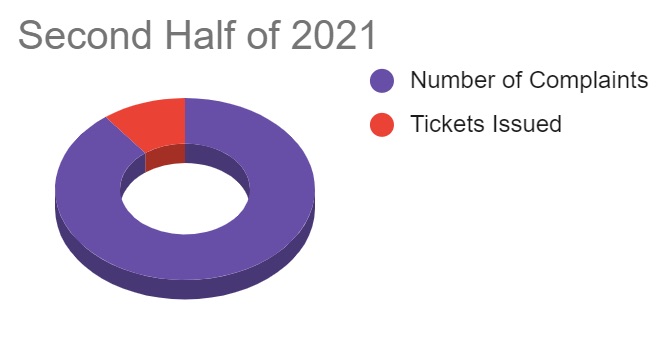

Enforcement is often a response to complaints from the general public, advocates, elected officials, community boards, and Business Improvement Districts (BIDs), which have historically viewed vendors as competition to brick-and-mortar businesses. Since Jan. 1, DCWP has received 1,455 complaints about street vending. In contrast, in the second half of 2021, DCWP received 6,525 complaints about vending and issued 762 tickets to vendors.

Complaints were concentrated in Manhattan in the first quarter of the year: 446 for general vendors and 576 for mobile food vendors; followed far behind by Brooklyn with 93 complaints about general vendors, and 66 mobile food vending complaints in Queens.

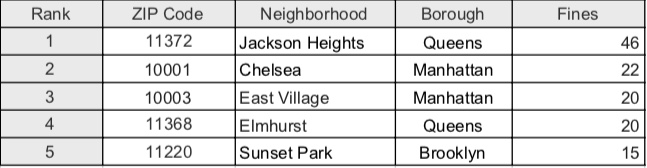

Zooming in to look at the most inspected zip codes, another picture emerges. Zip codes in neighborhoods with a large immigrant population continue to be among the most inspected and fined areas both in 2021 and during 2022’s first trimester, as previously reported by City Limits.

For example, Jackson Heights, Queens, where nearly 60 percent of residents are foreign-born, was the area with the most inspections for both mobile food vending and general vending: 176 and 164 respectively. Sunset Park, Brooklyn, had the highest number of inspections as of February 2022, but by the close of the first quarter, it dropped to third place.

Also, three of the five zip codes with the most fines were neighborhoods with a high concentration of immigrants as well.

“Vending is a complicated issue that touches us all—from the vendors themselves to local businesses to residents and visitors,” said a DCWP spokesperson via email. “Our goal is to hear concerns from everyone involved and strike a balanced approach that is equitable for all, which includes ongoing education coupled with scaled, strategic enforcement, especially in problematic areas.”

When asked how many educational outreach campaigns have been conducted this year, DCWP did not provide a clear answer, but said the agency spent the first half of the year conducting educational outreach with vendors and advocates, including nearly 30 educational walks in popular vending corridors to promote compliance.

From January to May of 2021, DWCP carried out 500 vendor education inspections and insisted that inspectors continue to educate every vendor before issuing a ticket. Advocates, on the contrary, say that the educational part has taken a back seat and that the agency is more focused on enforcement.

The issue is further complicated by the city’s decades-long cap restricting the number of available vending permits, which has made it nearly impossible for vendors to obtain one legally, critics of the system say—and which often result in fines for vending without a permit. For years, a black market of people renting and selling the limited number of existing permits has flourished, sometimes priced at tens of thousands of dollars a year.

While the City Council voted last year to gradually increase the number of legally available permits, those changes won’t begin until this summer, and critics say the legislation—which will add a few hundred new permits to the system each year—doesn’t go far enough to meet demand.

Another bill under consideration at the state level would take those reforms a step further by mandating the city come up with a licensing program that would “make sure every street vendor is licensed,” and which would ban the city from restricting or capping the number of licenses. The legislation has yet to pass, and lawmakers will wrap up their work in Albany on June 2.

3 thoughts on “Street Vendor Enforcement Continued at Pre-Pandemic Levels During First Quarter Under Mayor Adams”

The street vendors look like sh*t and steal business from legitimate tax paying local stores and restaurants.

Most of these illegal food vendors sell food bought with their ebt card (food stamps). Imagine making a profit out of tax payer dollars.

Not only are they here illegally but we continue to support this kind of behavior.

We have turned our neighborhoods into a disgusting place to live. Rats roaming all over, garbage in front our homes from food bought on 5th Ave. We are just about as filthy dirty as 8th Ave. Chinatown.

Food Trucks, fruit markets rolling into the street makes us an eyesore between Park Slope and Bay Ridge.

Sunset Park community needs a strong change in Community Board, Assembly, Council and Borough President who seem to encourage this type of behavior..

Oh and do not forgot the annoying bottle collectors that feel its ok at any time of the day to rummage thru your garbage. We should not be charged a deposit when bottles are recycled anyway.

The boardwalk at Coney Island now looks like a third world nation with hundreds of unlicensed, unregulated food vendors. Not only is the food of questionable safety, but these folks don’t contribute any taxes to the NYC coffers. Plus, they siphon off a huge amount of money from the legitimate businesses. At the boardwalk entrance by the aquarium on July 4th I counted 14 of these illegal vendors. I’ve been coming to Coney Island for decades and never seen a complete lack of law enforcement like there is now.