Akeem Loney was most at home on a patch of turf in Allerton. Outside the neighborhood, the 32-year-old—who was stabbed to death while sleeping on the subway last month—helped grow a citywide soccer program from a shelter on Wards Island.

Akeem Loney was most at home on a patch of turf in Allerton, his teammates say.

There in Bronx Park, Loney’s rare confidence and remarkable dribbling made him a star in the neighborhood’s competitive soccer scene. He was at the heart of the action in Saturday leagues and daily pick-up games that draw dozens of talented players, mostly from the local Caribbean and African communities.

Between games, Loney—or “Lonny” to his teammates—liked to sit at a particular spot near a corner flag, where he would listen to music and talk with other players.

“If you ask anyone, they’ll tell you, ‘He’s Allerton,” said Gio, 24, a friend who, like Loney, moved to New York City from Jamaica. “He was the person who everyone knows, and where he goes he represents Allerton.”

Outside the neighborhood, Loney, 32, used that influence to help grow a citywide soccer program from a shelter on Wards Island. He connected some of Allerton’s top players with coaches and volunteers from the organization Street Soccer USA and built a network of ballers, including many who, like him, were homeless. After years of playing together, the teammates formed bonds that only sports can foster.

So when Loney was stabbed to death while sleeping on the subway last month, the tragedy sent a tremor through the Allerton soccer community and rocked the tight-knit group of Street Soccer teammates. They decided to honor him with a tribute match on his favorite pitch.

“He really had a passion for soccer and I feel like if we didn’t do this for him, he’d be grieving his spirit,” said friend and teammate Sheldon Walker, 39. “He didn’t like negative energy. He fought against that.”

He described Loney as a natural leader—a product of his talent on the pitch and his personality off it.

“People would always look up to him,” Walker said. “I’m older than him and I looked up to him. He always pushed me.”

Adi Talwar

Honoring their #10

It’s a soccer custom that the number 10 jersey goes to the most creative playmaker on the team. The one player who influences the game above all others.

On a crisp and sunny Sunday morning, about 30 of Loney’s former teammates gathered in Bronx Park, each of them wearing a black or white jersey with the vaunted number 10 above the name “Loney.”

But before the formal tribute could begin Dec. 12, friends and teammates spent an hour playing against another group of locals who frequented the field for pickup matches—a testament to the rich soccer culture in that corner of the Bronx.

Along one endline, players who didn’t know about the special match still remembered Loney as a star footballer and a constant presence at the daily games.

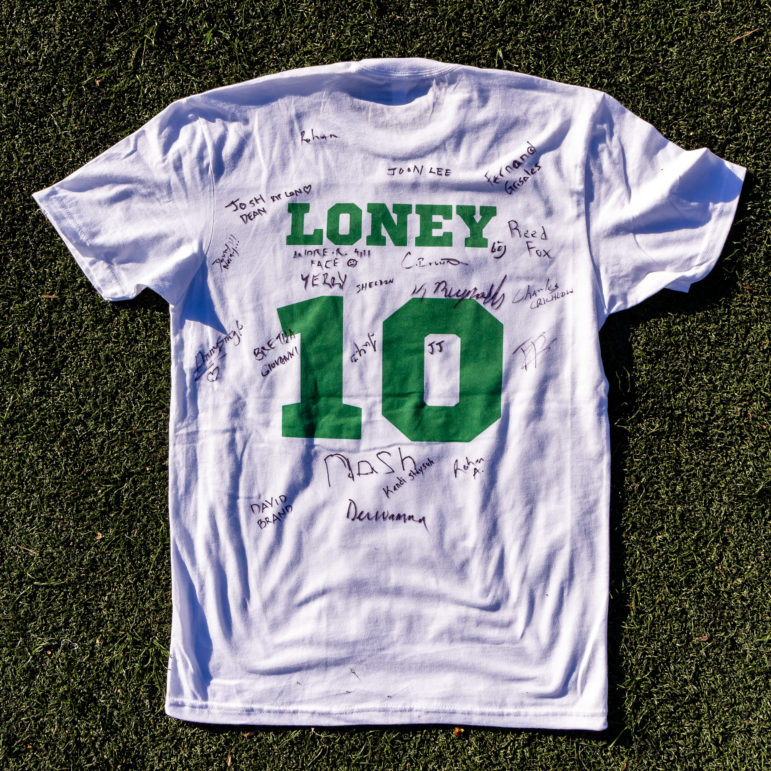

On the other side of the field, a lone number 10 jersey hung on the chain link fence, right above where Loney used to post up between games. Teammates signed the shirt, a gift to his family back in Jamaica, and shared memories of an industrious worker who spurred them to travel to practices on Ward’s Island—a hunk of land in the East River that’s home to sports fields and shelter facilities—while still making the game fun.

“He was normally the one who took people from here and brought them out” to Street Soccer, said Nash, a tall, 21-year-old Allerton footballer. “Lonny’s a guy that works. He’s always pushing good stuff.”

Gio, a physical therapy student at Hostos College, said Loney introduced him to Street Soccer after the two became friends. “I keep to myself, I train and then I leave,” Gio said. “But after a year or two, we started to talk and got really close. We started to kick it more because we’d go down to practice together.”

Gio served as the team’s holding midfielder, a position that complemented Loney’s role of attacking playmaker in the center of the field. The two became close friends outside the team, too. “We were partners in crime. I’d try to keep him out of trouble.”

Former college soccer player Lawrence Cann founded Street Soccer USA in 2005 to provide structured teams for children and adults who couldn’t otherwise afford to play an organized sport. Cann started the program in Charlotte, N.C., and expanded to 15 other cities, including New York.

The New York City adult program had fizzled by the time Reed Fox took over with a goal of reviving practices and building a team on Randall’s Island, a piece of land with a high concentration of both homeless shelters and soccer fields. But Fox struggled to attract players—that is, until he met Loney on the bus.

“He saw me in my Street Soccer shirt and saw I wasn’t getting any traction, and he said, ‘I’m a baller,’” Fox said. “And he brought his buddies from The Bronx and really got the program going.”

The team got good, winning in leagues and tournaments on Randall’s Island, the Upper East Side and elsewhere in the city. They practiced outdoors on the island on warm days and moved into a gym at a shelter run by the organization HELP USA during the fall and winter. More importantly, the team got close.

“We really became a family and that’s what it’s all about,” Fox said. “Not everyone has a family they can rely on.”

Those bonds are woven into the fabric of the team: Fox helped Loney move into an apartment in the Bronx three years ago, teammates travel to and from sessions together, and before taking the field for a match, players and coaches gather in a circle, put their hands together and shout “family.”

Photo courtesy of Josh Dean

Akeem Loney (second from left) poses with Street Soccer USA teammates after winning a tournament on the Upper East Side in March 2018Complicated by a pandemic

Over the years, Loney worked in restaurants and volunteered his time with Street Soccer, sometimes visiting schools to educate students about homelessness.

While staying at a shelter on Wards Island, he cooked meals on a hotplate and sold them to other residents, guards and staff for $3 each, Fox said. But as an undocumented immigrant, Loney faced obstacles when it came to finding a new home or a living wage job.

As the pandemic dragged on, Loney lost touch with his teammates; COVID complicated how they got together and competed. Fox moved to Sacramento to kickstart Street Soccer in California’s capital, and Josh Dean, founder of the homeless advocacy group Human.nyc, took over organizing and coaching duties in New York.

Dean has managed to unite the team even after the pandemic paused practices and shut down leagues across the city. He organizes weekly pickup games at Sara D. Roosevelt Park in Chinatown and canvasses the city to find and reconnect with teammates who have been injured on the streets, locked up on Rikers Island or shifted around to different shelters.

Fox told the Daily News that he thought Loney had a falling out with a cousin he was living with and began staying in shelters or sleeping on the subway. Throughout the summer and fall, Dean tried to reconnect with him, but Loney got a new phone and left the shelter system. Friends in Allerton said they hadn’t seen him in months.

About two weeks after Loney died at Bellevue Hospital, police arrested a suspect accused of the crime. Manhattan prosecutors charged the man, Jamoy Phillip, with second-degree murder and a judge ordered him held on Rikers Island without bail.

The killing underscores a disturbing reality: homeless New Yorkers, especially those staying in public spaces, are disproportionately the targets of violence, according to the National Coalition for the Homeless. “In that situation or circumstance, you’re very vulnerable,” said Ashley Belcher, outreach and organizing specialist at Human.nyc. “You never know who’s gonna pass you or what could come up to you.”

To Loney’s family, his death was a stunning tragedy.

“Despite his problems he showed resilience and tried to get his life back on track but he never got to show his true potential as his life was viciously taken away from him,” his stepmother Norina Gerald wrote in an online fundraiser seeking to raise money for family to attend his funeral.

For many of Loney’s teammates, Street Soccer remains an anchor: Walker and Gio show up to play in Lower Manhattan after their work days end. A friend of Loney’s appeared at one August session in his FedEx uniform before changing into a Belgium jersey. He dominated play that night. Another formerly homeless teammate got an apartment, a steady job and arrived at the concrete court on a new motorbike.

One regular player, Juan Carlos, moved to New Jersey and commutes back into the city for construction jobs each day. After the work day ends, he plays with his friends in the park.

Other teammates continue to face hard times.

Lionel, who answers to “Messi,” lives in a shelter in The Bronx and struggles to find work without an ID. He puts together whatever money he can to send back to his mother and son in Honduras. In recent months, he was beaten with a pipe by another shelter resident and hospitalized after getting food poisoning at a College Point hotel where he was placed by the city. Still, he shows up to play most nights.

“It’s more than a soccer team,” Dean said. “The guys were really supporting each other, and it was an outlet. We knew things weren’t going well in many respects in their lives, but they would show up for soccer.”

“The pandemic took that away, so it was important to bring it back,” he added.

Lonny’s Field

On the pitch in Bronx Park on the day of the memorial, Loney’s teammates showcased the skill that helped the Street Soccer team stand out. The last time some of them saw Loney was March 8, 2020, when they won an indoor tournament on the Upper East Side, a week before the city’s pandemic shutdown.

They recalled Loney’s constantly churning legs, which deceived defenders and exposed them to his prolific nutmegs—a prize for an attacking player (The nutmeg, slipping the ball through an opponent’s legs, is also utter humiliation for a defender).

“In terms of dribbling, he’s the best,” Gio said. “Even the best of the best guys, he has dribbled everyone out here and he probably nutmegged you three or four times.” But that’s OK, said Gio, who also possesses the ball with skill and confidence, “as long as you can give it back.”

When the match ended, the players gathered in the middle of the field to pose for photos. They turned their jerseys around so that Loney and the number 10 faced forward.

Earlier, Nash had surveyed the crowd and pointed out the connections he made through Lonny.

“They’re good people,” he said. “And if it weren’t for Lonny I wouldn’t know that. He’s the glue.”