Many of the issues homeless new Yorkers with health problems face—abrupt transfers, inaccessible accommodations, shelters in isolated areas—existed long before the pandemic, but they have been laid bare as Mayor Bill de Blasio continues to pursue a summer-long effort to clear about 60 so-called “de-densification” hotels.

Adi Talwar

Darren Whitney is staying at the Clarke Thomas Men’s Shelter on Wards Island, as he awaits a hip transplant and permanent housing.

Kenneth Jones learned he lost his room in an East New York hotel, rented out as a temporary homeless shelter, as soon as he returned from Brookdale Hospital last week. He said he had been in the hospital for three days for emergency heart treatment after a staff member at the hotel called 911, but he didn’t notify the shelter provider about his admission. Under city shelter rules, he was AWOL and forfeited his spot.

A few days later, Melvin Green returned to the same hotel, only to find that staff had thrown away his possessions, perhaps assuming he had already been transferred to another location, he said. Green has diabetes and four stents in his heart and said he had to rush to get new diabetes medications and blood thinners from his physician to avoid the emergency room.

Twelve miles north, at the Clarke Thomas Men’s Shelter on Wards Island, Darren Whitney awaits a hip transplant and uses a walker to get around. He said his doctor won’t approve the surgery until he finds a permanent home; the risk of infection is too great in the barracks-style shelter and Whitney can’t have a home health aide inside the building.

“All I need is a place,” Whitney said Monday. “Once I get a place, my problems are over.”

The three men, backed by advocates and some city lawmakers, say their situations illustrate the desperate need for permanent housing for homeless New Yorkers with disabilities and other serious health problems —as well as the routine degradations and burdens they experience.

Many of those issues—abrupt transfers, inaccessible accommodations, shelters in isolated areas—existed long before the pandemic, but they have been laid bare as Mayor Bill de Blasio continues to pursue a summer-long effort to clear about 60 so-called “de-densification” hotels. The city rented out one- and two-bed hotel rooms at the beginning of the pandemic to house roughly 10,000 homeless adults and stop the spread of COVID-19 among some of the most vulnerable New Yorkers. The Federal Emergency Management Administration has said they would reimburse the city for the rooms through the end of the year.

The hotel clearance plan began at a fevered pace in June, with disabled residents rushed back to sites that did not meet their needs with little notice. Homeless New Yorkers challenged the moves in court, prompting judges to slow the rate of transfers.

De Blasio has stuck with that policy despite the legal challenges and court-ordered delays. Earlier this month, just under 2,000 adults were left in the remaining hotels, according to court documents filed by the Department of Social Services (DSS) in an ongoing legal battle over the policy.

Homeless rights advocates and some policymakers say the transfers have exposed an existing, broken status quo in the shelter system, particularly when it comes to people with health needs.

“There’s been a rush to get back to normal, but I don’t think ‘normal’ was very good,” said Public Advocate Jumaane Williams Monday. He spoke with City Limits as he waited for a bus to visit a shelter on Wards Island, part of a fact-finding trip organized by advocates for homeless New Yorkers. He has called on de Blasio to halt the transfers back to congregate shelters and instead end the hotel deals only after residents access permanent housing.

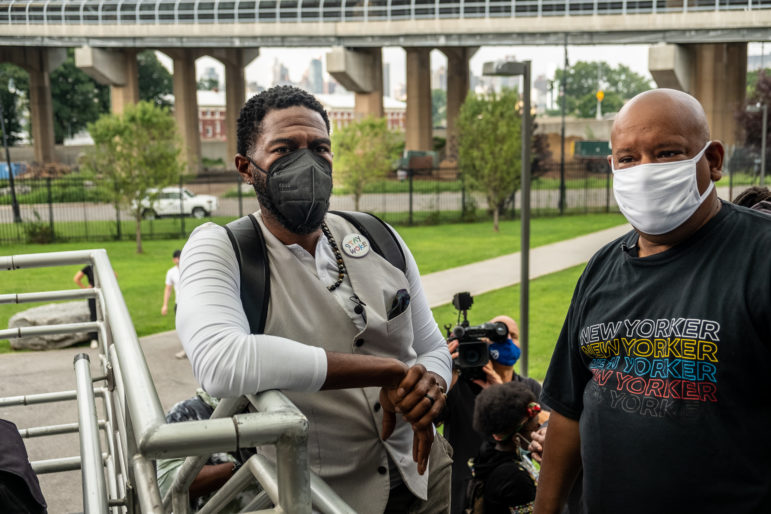

Public Advocate Jumaane Williams and activist Shams DaBaron waiting to get access to the Clark Thomas Men’s Shelter on Ward’s Island.

The M35 is the only bus that serves Wards Island.

Elected officials and advocates tour the homeless shelters on Wards Island.

A view from MTA’s M35 as it arrives on Ward’s Island.

A resident of the Clark Thomas Men’s Shelter on Ward’s Island complaining about living conditions there.

“Sometimes mayors get wedded to very bad policy and I don’t understand it,” he said. “It’s not a very good legacy item.”

De Blasio has repeatedly said the shelters are safe, despite a citywide surge in cases of the delta variant, and city officials have highlighted a robust vaccination program led by DSS, which says it has provided 21,750 vaccine doses to shelter clients and staff.

“DSS-DHS has worked together with provider partners throughout the pandemic to protect our clients and implement safety protocols, like proactive COVID testing, vaccination, isolation/quarantine services, and more — and those efforts have paid off,” a spokesperson said, citing a small incidence of cases relative to the citywide population.

Nevertheless, a significant number of shelter residents and employees remain unvaccinated and unwilling to get the shot.

Advocates, however, say there is reason for hope—so long as the city and its shelter providers act quickly. Federal initiatives and recent municipal legislation championed by homeless New Yorkers give the city an opportunity to drastically decrease the shelter population by helping residents secure permanent housing.

On Tuesday, the Human Resources Administration will raise the value of rental subsidies issued to homeless New Yorkers, allowing them to access more apartments in the country’s most expensive rental market. The increase to the CityFHEPS housing voucher could potentially unlock tens of thousands of homes across the city.

City officials have also allowed more homeless New Yorkers to apply for nearly 8,000 federal emergency housing vouchers, reversing an earlier decision to prevent people approved for supportive housing from applying.

The stronger subsidies could open up more buildings with elevators or space for wheelchairs for New Yorkers with disabilities and health problems, said Erin Kelly, the director of health policy and partnerships at the organization RxHome.

“There’s a genuine gap in the city’s system around people who need this higher level of care that the DHS shelter system is not equipped to provide,” said Kelly, a former senior adviser at the agency. “If I were able to make city systems work as well as they could, I would connect folks who need this high level of care with CityFHEPS and housing choice vouchers, and then make sure they have the Medicaid-funded services they need.”

Dr. Betty Kolod, an East Harlem primary care physician and member of the New York Doctors Coalition, said the city should aggressively roll out the vouchers for homeless New Yorkers.

And with the stronger subsidies in effect, “it makes no sense to send people back into shelters,” she said.

A three-borough journey

Overall, the DHS shelter population—44,904 New Yorkers, including about 8,300 families with children—is at its lowest rate in nearly a decade. The decrease is driven by a significant drop in the number of families with children in shelters following concerted efforts by advocates, city officials and nonprofit staff to get families into permanent housing.

DHS says about 19,000 people moved out of their shelters and into permanent homes in 2020. At the same time, statewide COVID-19 eviction protections have prevented many at-risk families and individuals from entering the shelter system.

There were 16,162 single adults living in DHS shelters on Aug. 29, according to the city’s most recent census. That’s down from 17,685 on an average night in August of last year, but still more than double the 8,235 on an average night in August 2011—a sign of the city’s worsening affordable housing crisis over the past decade.

People living in homeless shelters are more than twice as likely to have a disability than the general population, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development reports. A disproportionate number of homeless New Yorkers also experience serious, chronic health problems like heart and respiratory illness.

Jones, 62, became homeless in January when he decided to leave a friend’s house, where he had been staying, because he felt uncomfortable with the number of visitors coming in and out, potentially bringing COVID with them.

“With my illness, I’m vulnerable to a lot of things,” he said. “I had to make a decision to leave.”

Jones was assigned to the Williams Hotel in East New York, near the Brownsville border, one of the hotels rented out to limit the spread of COVID-19. On Aug. 20, he experienced chest pain and asked a worker at the hotel to call 911, he said. An ambulance transported him to Brookdale Hospital where he was admitted for three days.

When he returned to the hotel on Aug. 23, he learned his room was gone—a standard rule in the shelter system for people who leave the sites or miss curfew without notifying the provider.

“It was all new to me. People might think, ‘Oh, you should have known this particular rule’ and I honestly didn’t,” he said. “It seems like every other moment something else comes up.”

He said he was told to leave at 1 a.m. and given two Metrocards to travel to a Far Rockaway congregate shelter, despite being granted a “reasonable accommodation”—approval for a private, ground-floor room to meet his health and mobility needs. When he arrived there a few hours later, shelter staff saw he’d been granted the accommodation and did not belong in a group setting.

“They noticed it was on file and the lady told me, ‘You don’t belong here. This is a shelter setting. There’s like 15 people to a room,’” he said. He learned he would instead be staying at a Radisson Hotel in Manhattan’s Financial District, and boarded another set of trains to get there. At first, he wasn’t yet on the roster there either, he said.

“From the beginning, it was anarchy,” he said.

By the time he spoke with City Limits on Aug. 25, Jones said his situation seemed somewhat stable and he was preparing to meet with a new case manager. But a few hours later, Jones learned he was being transferred again, this time to the Sweet Home Suites in Long Island City, a long commute from his doctors and treatment program in Brooklyn.

He said he worries how the moves will affect his ability to access an apartment after working for nearly a year with the same case manager from the organization CAMBA at the Williams Hotel.

“From what I understand, after putting in 10 months of work to establish myself, getting an apartment now I have to start all over with a new case manager and so on and so on,” he said. “I’m trying to keep my composure and roll with the punches so to speak.”

DHS declined to comment on the experience of specific individuals, but has acknowledged in court that there have been problems with the hotel transfers similar to the issues that Jones experienced.

The agency has also pointed to several improvements in its hotel transfer initiative in response to judges’ orders. The city has managed to close 34 of the more than 60 hotels rented out last year because of the pandemic, though paperwork filed as part of ongoing litigation said only 19 of the hotels remain open.

About a month into the moves, Legal Aid and the law firm Jenner Block challenged the policy in court on behalf of homeless New Yorkers with disabilities transferred to shelters that did not meet their needs—like a person in a wheelchair sent to a shelter on a steep hill and another to a building without a working elevator. A judge ordered the city and nonprofits to give residents clear notice before the transfers and to inform them of their right to apply for reasonable accommodations.

Three weeks later, another judge temporarily halted the moves, ruling that the process still proved too chaotic for many people with disabilities or illnesses who ended up in buildings without elevators or refrigerators for their medications.

But the judge, Valerie Caproni, agreed with the intent of the policy and said the city could continue the moves as long as staff read an approved script to each client regarding their right to apply for reasonable accommodation, consider each individual reasonable accommodation request and give applicants 10 days to submit supporting documentation before a transfer. The plan, approved by the court, also mandates that DHS give clients an opportunity to appeal a denial.

“We thank the court for again affirming our plans to return to shelter and allowing us to proceed with the phaseout of the temporary hotels, including the adjustments we made to continue ensuring we protect client safety, appropriately meet each individual’s unique needs, and engage person by person the clients affected by the transition, as we have endeavored to do throughout this process,” a DHS spokesperson said in a statement. “We are resuming these efforts and look forward to phasing out this temporary program, as the Mayor has said we would.”

For Green, the hotel phase-out plan took place a few hours too soon. He said he was supposed to be transferred on Aug. 26, but when he returned to the hotel about a half hour after curfew, his belongings were gone. Hotel maintenance staff had discarded his things, including his various medications, he said. He filed a police report the next day with the 75th Precinct. The provider, CAMBA, did not respond to a request for comment. The hotel could not be reached.

“My medications, clothes, paperwork, food, toiletries. All gone,” Green said. “I accumulated a lot of stuff, living there four to five months.”

Green, 40, has had two heart attacks and also has a reasonable accommodation for a private room. He was transferred to a hotel in Manhattan and managed to get his medications from a primary care doctor, he said. On Monday, he said his health was stable.

Isolated on Wards Island

A group of advocates and lawmakers gathered at the corner of East 125th Street and Lexington Avenue Monday morning to take the M35 bus to Wards Island, site of six shelters and a massive psychiatric institution.

The patch of land in the East River has for centuries housed New York City’s most marginalized and stigmatized—smallpox patients in the 18th Century, orphans and children charged with crimes in the 19th Century, people with severe mental illness in the 20th Century. Today, there are hundreds of adults experiencing homelessness staying in the island’s various facilities.

The trip to Wards Island was organized by Shams DaBaron, a formerly homeless advocate who goes by the nickname Da Homeless Hero and spent time at an island shelter. He urged lawmakers and reporters to talk with many of the residents with disabilities at one of the sites, the Clarke Thomas Men’s Shelter operated by the organization HELP USA.

The problems the residents experience illustrate the obstacles that have existed for homeless New Yorkers with health needs long before COVID-19 pandemic, like the wide open shelter rooms where dozens sleep and the isolation of the island, served by a single bus line. The M35 bus to Wards Island has just two wheelchair accessible spots. When both were occupied Monday morning, a man with a wheelchair outside the Clarke Thomas shelter could not board and had to wait for another bus to come around.

A resident of Ward’s Island speaking with the driver of the M35 bus, the only one that travels to the island. He was refused access to the bus because it had already reached its limit of two wheelchairs.

Delroy Gordon, who has been at the Clarke Thomas Men’s Shelter since July after being transferred from a hotel in Midtown Manhattan.

Kris Sergentakis, who was also transferred back to the Clarke Thomas Men’s Shelter after staying at a hotel in Midtown Manhattan.

Many residents of the building shared photos of the conditions inside—rows of beds lined up in a large room and dirty bathrooms among them. The building is wheelchair accessible with a long ramp leading to the front door.

A DSS spokesperson said the de Blasio administration has “invested hundreds of millions of dollars in our shelters and shelter providers to address the challenges that we inherited following decades of neglect and underfunding because we know the comprehensive transformation we’re focused on achieving doesn’t come free, including on Wards Island in partnership with HELP USA.”

But Whitney, 60, honed in on the fundamental problem with shelter life: Residents do not have a secure home to call their own. “What do I have to do to get housing?” he said. “We’re in limbo here.”

Whitney said he became homeless immediately after his release from prison in 2017 and he was paroled to a shelter, a common occurrence that helps drive the homelessness crisis in New York City.

Over the past six months, he has been transferred from a shelter in Midtown Manhattan to a site in the Bronx to Wards Island, moving around with his walker and imploring his doctor to authorize his hip replacement, he said. The doctor has refused.

During that time, he has never managed to visit an apartment with the help of a shelter housing specialist, he said. The move to Wards Island has only exacerbated the challenges.

“You have to get on a bus into Manhattan to do anything,” he said. “There’s no pharmacy here. There are no apartments here.”

“You’re away from everybody,” he added. “When they put you here, it’s usually to forget about you.”

One thought on “Pandemic Worsens Hard Road to Housing for Homeless New Yorkers with Health Needs”

As a resident of this facility hopefully instead of this story just becoming another sound bite maybe something will actually be done and we will get housing. I’ve been in Clarke Thomas for 3 years with little to no help with housing. It’s a serious problem that will only get worse if it’s not taken care of in a timely manner.

MW