The tragedy galvanized residents of 710-720 Hunts Point Ave., where the incident took place, to demand safer conditions. A half decade later, they’re still fighting for fixes. “We’ll never forget that day those little girls died,” tenant association leader Annie Martinez told City Limits. “And they haven’t changed anything since.”

Adi Talwar

Windows to the first-floor apartment where two sisters, Ibanez Ambrose, 2, and Scylee Vayoh Ambrose, 1, died after a radiator spewed scalding hot steam into their room on Dec. 7, 2016.Five years ago Tuesday, a broken radiator spewed scalding hot steam into a Bronx apartment, killing two baby sisters and exposing the dangerous conditions inside privately-owned buildings used as shelters for thousands of homeless families.

The deaths of Ibanez Ambrose, 2, and Scylee Vayoh Ambrose, 1, fueled an effort to end the city’s cluster-site program, which gave landlords big payouts in exchange for use of their vacant, and often substandard, apartments—a goal the city’s Department of Homeless Services finally accomplished in October.

The tragedy had another impact: galvanizing residents of 710-720 Hunts Point Ave., where the incident took place, to demand safer conditions from the property owner, Moshe Piller, and his management company. Renters there formed a tenants’ association and worked with a lawyer to force some short-lived improvements from Piller, a fixture of the public advocate’s worst landlord list.

A half decade later, they’re back at it.

“We’ll never forget that day those little girls died,” tenant association leader Annie Martinez told City Limits inside her fourth-floor apartment Oct. 19. “And they haven’t changed anything since.”

That same week, Martinez organized a meeting in the building’s concrete courtyard to discuss the many problems tenants have encountered. About two dozen residents showed up to decry the perpetually broken elevator that leaves seniors stranded and to say their cracking walls reminded them of a recent Florida condo collapse. They listed their busted appliances and lengthy replacement delays—six weeks for a refurbished fridge, two years for a new stove. And they discussed the malfunctioning heating system that still floods their floors with water and, they fear, may once again pump steam into their homes.

The experience of one third-floor tenant, Maria Martinez (no relation to her upstairs neighbor Annie), highlighted those continuing concerns.

Martinez slipped on water that poured out of her radiator in January 2018 and severely injured her back, requiring multiple surgeries, neighbors said. Annie Martinez said her husband descended the fire escape to the apartment below and found Maria laying in a puddle.

“The radiator water was so hot, she slipped and fell on it and broke her back,” Annie Martinez said.

Maria Martinez’s attorney Glenn Shore gave a similar account, saying his client “lived alone and was screaming in her apartment so loud that a neighbor came down and responded to the scene.” Martinez sued the Piller-connected LLC that owns the building in 2019.

The landlord’s attorney Frank Garufi declined to comment on the litigation.

Maria Martinez has since died, her neighbors said. But faulty radiators remain a persistent fear, even after workers added new caps and valves in individual apartments, said Annie Martinez.

“We just want to make sure this place is safe,” she said.

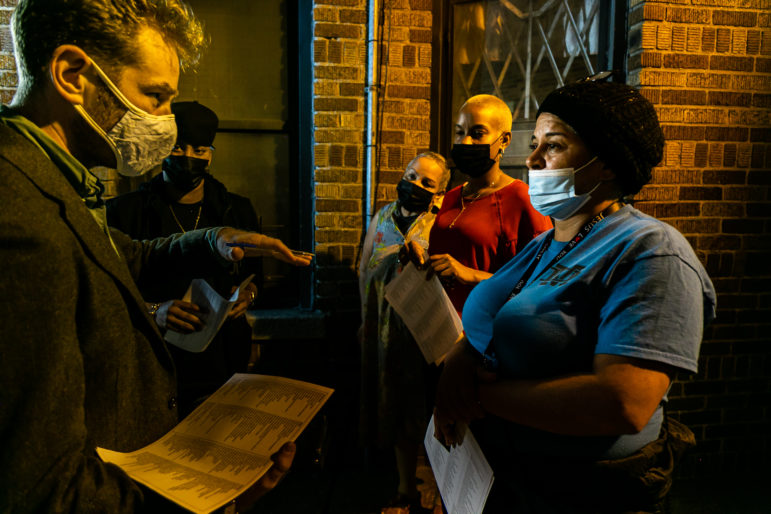

Attorney Michael Leonard of the organization TakeRoot Justice talks with tenants about the problems inside their building at 710-720 Hunts Point Ave. in October.

Fifth-floor tenant Carmen Ortiz said she frequently returns to the building from her doctor’s appointments only to find the elevator broken. She takes a cab to her daughter’s home because she cannot climb the stairs, she said.

The property at 710-720 Hunts Points Ave. in The Bronx, where a radiator explosion killed two baby sister in 2016.

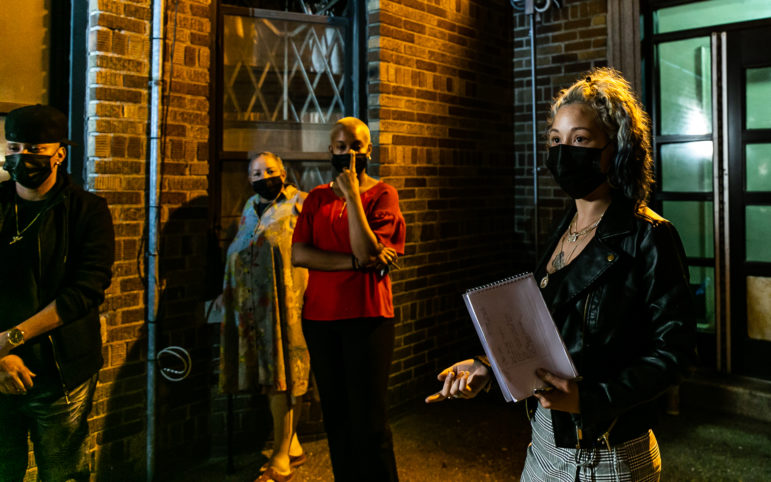

Tenant Mailin Evangelista speaks out about conditions in the building during an October tenants’ association meeting.

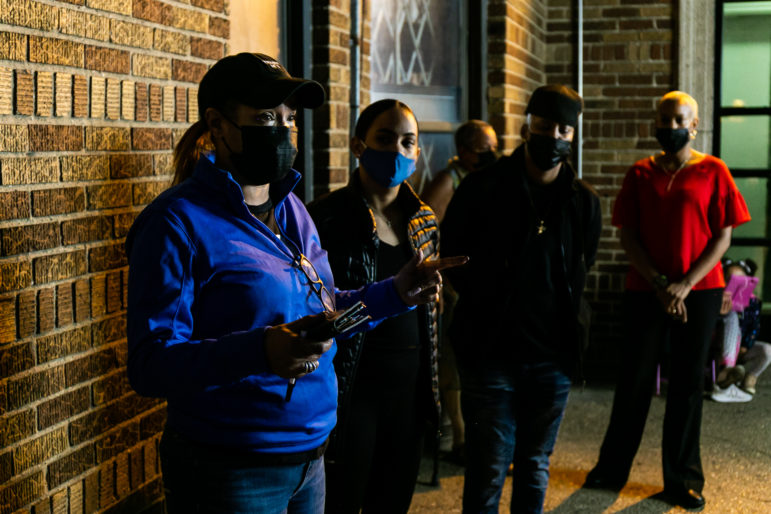

Tenant association leader Annie Martinez describes problems she and her neighbors have encountered in their building during an October tenants’ association meeting.

Tenant association leader Annie Martinez talks with neighbors during the group’s October meeting.

Attorney Michael Leonard of the organization TakeRoot Justice talks with tenants during an October meeting. Leonard represented residents of 710-720 Hunts Point Ave. when they took their landlord to court to compel repairs in 2018.

Aftermath of a tragedy

A day after the radiator burst killed the two girls on Dec. 7, 2016, Mayor Bill de Blasio visited the Hunts Point Avenue apartment and pledged to end the use of cluster-sites—though he was careful not to assign blame for the girls’ deaths.

“This was a freak accident, a series of painful coincidences that led to the loss of these children,” he said at the time.

Attorneys for the city have since shifted their stance, attempting to pin responsibility on Piller and the nonprofit shelter provider Bushwick Economic Development Corporation, or BEDCO, in response to a 2017 lawsuit filed by the girls’ parents Danielle McGuire and Peter Ambrose. Nicholas Paolucci, a spokesperson for the city’s Law Department, called the deadly radiator blast “a tragic incident.”

The parents’ lawsuit also names Piller and BEDCO as defendants but remains stuck in the discovery phase, with the COVID court slowdown contributing to delays, according to lawyers for the various parties.

Joseph Goodman, an attorney representing McGuire and Ambrose, said the family is seeking justice for their daughters.

“There’s been no acknowledgement of responsibility. Nobody has acknowledged fault,” Goodman said. “The building has multiple reports of problems similar to what happened on that night that gave them adequate notice of items that needed to be addressed. BEDCO, the building management and the city all failed to respond to repeated safety concerns voiced by tenants of the building.”

The parents, who moved to Maine following the death of the children, could not be reached for this story. “They continue to struggle with the unfortunate and tragic loss of their children and they’re not looking to talk with the media,” Goodman said.

An attorney for Piller and his firm 710 Hunts Point Equities—the limited liability company listed on building records—did not respond to multiple questions by email or phone. BEDCO’s lawyer Suzanne Halbardier declined to comment on the pending litigation.

BEDCO, which once provided services for families in five cluster units in the building, no longer operates shelters in New York City at all. A few months after the radiator blast, de Blasio announced that the city would cut their contracts. The organization, marred by financial improprieties, later lost its last two agreements for stand-alone shelters and shut down for good.

At its 2016 peak, the city’s cluster program included 3,650 units spread across the five boroughs, according to the Department of Homeless Services (DHS). Untangling that network of apartments and moving families into permanent homes or new temporary accommodations posed a significant challenge for a city agency that had become dependent on bad landlords with flexible housing stock amid a record-high homelessness crisis.

Over the next five years, DHS officials set out to end the program once and for all. In some cases, the city negotiated the purchase of entire buildings where cluster units were concentrated and turned those apartments into permanent homes. In other instances, officials moved people out of the units and into purpose-built family shelters.

READ MORE: No Longer a ‘Cluster Site,’ But Problems Remain for Tenants

The final cluster site apartments closed in October, earning praise from the homeless New Yorkers and their advocates who led the fight to shut down the hazardous arrangement even before the Bronx tragedy. But the same advocates say the city should also step in to ensure the buildings remain safe and well managed, even after they’re no longer being used for shelter.

“That was an example of the most dangerous living conditions in clusters and this really brought it to the fore for the administration,” said Ryan Hickey, a former staff member with the group Picture the Homeless, which urged the city to get out of clusters. “The ultimate goal wasn’t just to end the program, even though that was extremely important. The ultimate goal was to see these buildings in responsible management.

“It’s about improving conditions so that tenants’ rights are fully realized,” he added.

Tenant Carmen Ortiz (left) takes the elevator up to her fifth-floor apartment with her home health aide. When the elevator breaks, Ortiz said she is stranded inside her home because she cannot take the stairs.

Cracking walls on the first floor of 710-720 Hunts Point Ave.

Francisca Deoleo, 90, inside her fourth-floor apartment. Her daughter Carmen said family and neighbors are forced to carry Deoleo up to the apartment when the elevator breaks.

The broken stove inside Carmen Deoleo’s apartment.

Reactivating a tenant’s union

Many tenants in buildings used as cluster sites continue to face problems caused or abetted by negligent landlords, with Piller standing out as a particularly egregious example.

He avoided criminal charges following an investigation by the Bronx District Attorney’s Office and continues to collect rents on thousands of units across the South Bronx, Northern Manhattan and Central Brooklyn—all while evicting tenants at a higher rate than nearly every landlord in the city.

A review of property listings through the online tool Who Owns What shows Piller with ownership ties to 61 buildings accounting for 49,292 violations from the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD). The agency has added just one property, a 42-unit complex at 2020 Albemarle Road in Brooklyn, to its Alternate Enforcement Program, which allows HPD to levy modest fines and potentially hire a contractor to make necessary repairs at the owner’s expense.

Since March, HPD has sued Piller and his various firms at least 10 times to force repairs, turn on the heat or resolve phony violation certifications at nine properties. Those cases have resulted in a few thousand dollars in fines.

But even when tenants do achieve victories against Piller and his LLCs, the wins can be fleeting. That’s partly why the tenants at 710-720 Hunts Point Ave. are organizing once more. There are currently 61 open HPD violations across the two buildings, including for mice and roach infestations, mold and missing or defective smoke and carbon monoxide detectors, city records show.

Building tenants took Piller to housing court in 2018 to repair a broken elevator via a legal action known as an HP case. A few months later, they won. A judge ordered Piller to replace the elevator in May 2019 and Piller agreed not to shift the cost of the renovation onto tenants through a Major Capital Improvement rent increase.

“The tenants made real progress in 2019 when they sued the landlord and forced him to replace the elevator and waive rental increases,” said their attorney Michael Leonard of the organization TakeRoot Justice. “But they will need more oversight and enforcement from the city and state in order to get this landlord to start respecting the tenants.”

Two and half years later, the elevator is broken again—a life-altering inconvenience for seniors in the highest floors of the six-story building.

“Sometimes it’s working in the morning and I come back from an appointment and it’s not working,” said fifth-floor resident Carmen Ortiz, who uses a walker to get around, during the October tenant association meeting. “I have to make a trip to my daughter’s in Williamsbridge.”

Francisca Deoleo, 90, and her daughter Carmen also know the problem well. Carmen Deoleo said she frequently taps a team of family members and neighbors to carry Francisca up to and down from their fourth-floor apartment when the elevator breaks.

Mailin Evangelista, who lives with her 10-year-old daughter, said she regularly tries to help her older neighbors.

“It’s sad to have to come and see these older people who pay for an elevator and we have to help them up,” Evangelista said. “Old people get stuck in the elevator. It’s ridiculous.”

But Evangelista and her daughter are dealing with problems of their own. They went two years without a functioning stove and were forced to buy their own refrigerator, she told other tenants at the association meeting.

In an interview, Evangelista said she moved into the building around the same time as the Ambrose girls and their parents and knew the family from a previous shelter. Unlike them, Evangelista said she and her daughter had a rental assistance voucher that covered their rent for a permanent apartment.

The girls’ death was traumatizing, she said, and as problems mount, she is thinking of finding a new home.

“It’s too much already,” she said.

A few minutes later, second-floor tenant Joanne Duncan, 65, walked over to the meeting and described the problems she has faced since moving to the building in 2008. Most recently, she went about six weeks without a refrigerator despite repeated complaints to management and 311, she said.

She quickly exhausted food stamps replacing spoiled food and struggled to keep her medications cold, she said.

“I came from a shelter and I was glad to get here, but I’m human. I’m supposed to live in a decent apartment,” Duncan said. “We should be able to live decently.”