The ruling comes less than two weeks after the Supreme Court ended New York state’s ban on most evictions. But NYC tenants still have several other potential avenues of protection.

Marc Fader

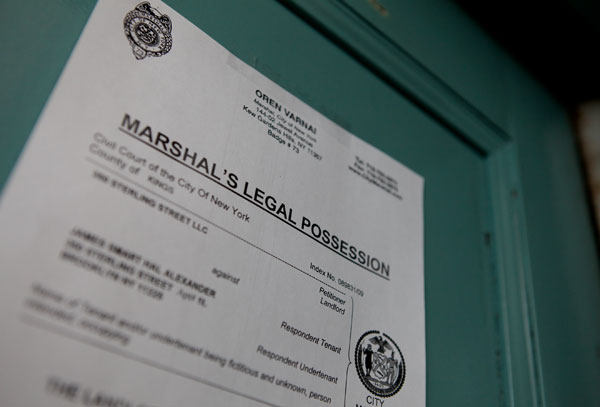

A marshal’s eviction notice, seen in 2010The U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday struck down a federal eviction freeze designed to keep tenants housed in places with high rates of COVID-19, criteria that covered most of the country, including all of New York City. But several protections remain intact for most renters in the five boroughs—so long as they are aware of them.

The Supreme Court’s six conservative judges ruled that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lacked authority to impose a blanket eviction ban, and said only Congress could establish a future moratorium.

“It is indisputable that the public has a strong interest in combating the spread of the COVID-19 Delta variant. But our system does not permit agencies to act unlawfully even in pursuit of desirable ends,” the judges wrote. “It is up to Congress, not the CDC, to decide whether the public interest merits further action here.”

The court’s three liberal justices dissented, citing legal and public health considerations.

“It is far from ‘demonstrably’ clear that the CDC lacks the power to issue its modified moratorium order,” wrote Justice Stephen Breyer. “The CDC’s current order is substantially more tailored than its prior eviction moratorium, which automatically applied nationwide. Justified by the Delta-variant surge, the modified order targets only those regions currently experiencing skyrocketing rates.”

The ruling comes less than two weeks after the Supreme Court ended New York state’s ban on most evictions. In his dissent, Breyer contrasted the federal moratorium to New York’s former eviction freeze, which allowed tenants to automatically halt eviction proceedings by submitting a “financial hardship declaration” form—a sworn statement avowing that they had suffered an economic impact as a result of the COVID crisis. The federal protections still allowed landlords to challenge tenants’ hardship claims, he argued.

But the court sided with an Alabama landlord group that had challenged the federal freeze. The decision earned praise from property owners in New York. The ruling “supports what we have been saying from the outset of the pandemic—that lawmakers and government agencies have continually abused powers that have violated the property rights of private landlords,” said Rent Stabilization Association President Joseph Strasburg, whose organization represents 25,000 owners in New York.

The decisions have ended blanket protections for most tenants in New York, amid a creaky rollout of the state’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP). ERAP, funded with more than $2 billion from the federal government, pays landlords up to a year of back rent and three months of future payments on behalf of low-income tenants financially impacted by the pandemic.

The applications not only allow landlords to recover lost revenue, they also ensure tenants can remain in their apartments for at least another year. Even tenants whose landlords have not completed their portion of the application can temporarily stave off eviction by showing proof of their submission in Housing Court.

Ellen Davidson, a supervising attorney in Legal Aid’s Housing Unit, said her organization is urging tenants to apply for ERAP to recover back rent and to remain in their homes.

“In New York City, this shouldn’t impact a huge number of people because it has happened so quickly after the SCOTUS decision on the [state’s] moratorium. We don’t believe there are many people only protected under the CDC moratorium,” Davidson said. “But outside New York City, if you are in one of the non-ERAP jurisdictions you don’t have any protections.”

Nine counties and municipalities, including large jurisdictions like Yonkers and Hempstead, have opted out of the state ERAP in favor of their own programs. Tenants there and elsewhere in the state lack the same protections as renters in the five boroughs.

“I am concerned both for New York City tenants, but especially for tenants upstate who have fewer protections,” added Justin La Mort, a supervising attorney at Mobilization for Justice.

La Mort said he and his colleagues have already met with New York City tenants who received eviction notices in the days since the Supreme Court struck down the state’s ban.

Tenants ordered out of their apartments by a judge prior to the pandemic but who were able to stay in their homes as a result of the state moratoria are now at particular risk, advocates say.

Nevertheless, low and middle-income tenants in New York City have access to an attorney in Housing Court under the city’s right-to-counsel law. New York’s year-old Tenant Safe Harbor Act also enables tenants who missed rent payments during the pandemic to use proof of COVID-related hardship as a defense against eviction.

“The federal moratorium has had little effect when it comes to New York City tenants, but it’s still very disappointing. Tenants are still protected by ERAP and the Tenant Safe Harbor Act and I am hopeful that Congress and Albany will take action while this pandemic continues to rage on,” La Mort said.

The issue of establishing a new state eviction moratorium in a way that complies with the Supreme Court ruling has divided local lawmakers. Landlords groups have come out strongly against another freeze.

But tens of thousands of property owners, and hundreds of thousands of tenants, could benefit from the state’s rent relief fund, which would ensure more people can remain in their homes.

After a slow start, ERAP has begun cutting checks to thousands of property owners, distributing $203 million in rent relief as of Aug. 23. State officials have approved another $605 million on behalf of over 46,400 applicants but have not yet distributed that money.

Roughly 176,000 people statewide have so far applied for ERAP payments, still a fraction of the more than 830,000 tenants who owe some back rent, according to estimates. Qualifying tenants must earn no more than 80 percent of Area Median Income—$95,440 for a family of four, or $66,880 for a single person in New York City—and demonstrate that they were financially burdened by the pandemic.

Newly released data from the Office of Temporary and Disability Assistance, which administers ERAP, shows that the state’s lowest income residents make up the vast majority of applicants so far. About 90 percent of those who applied in New York City earn less than 50 percent of Area Median Income (AMI); about 71 percent earn less than 30 percent—$25,080 for an individual and $35,790 for a family of four.

In New York City, Black and African American New Yorkers account for more than 45 percent of submissions, while Latino or Hispanic residents make up about 39 percent.

Women completed nearly two-thirds of the state’s ERAP applications, highlighting a trend among families experiencing homelessness or at risk of losing their homes. Across the five boroughs, households headed by single mothers of color make up the vast majority of homeless families.

There are more than 1.3 million renter households earning less than 80 percent of AMI, with OTDA estimating that nearly 400,000 experienced a financial hardship from COVID-19, according to agency data shared with nonprofit providers.

Less than a third of likely qualifying households have so far applied for ERAP, however.

The problem is particularly stark in the Bronx, home to the six community districts with the highest number of households in rent arrears. In Community District 7 (Bedford Park, Fordham North and Norwood), 8,021 households owe rent; in Bronx Community Districts 1 & 2 (Hunts Point, Longwood and Melrose), it’s 6,511, according to OTDA figures. In Community District 5 (Morris Heights, Fordham South and Mount Hope), there are 6,217 households behind on rent, while in Community Districts 3 and 6 (Belmont, Crotona Park East & East Tremont), 5,544 households are in arrears.

For months, nonprofit groups and some state lawmakers have sounded the alarm on the need to better publicize the program, while increasing outreach in the most affected communities.

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul on Tuesday pledged to step up that effort, starting with directing $1 million to fund additional outreach and releasing more county and zip code-level data.

“The pandemic thrust countless New Yorkers into financial turmoil and uncertainty, leaving many struggling to pay their rent,” Hochul said Tuesday. “By expanding and better targeting our marketing and outreach efforts, we can raise awareness in the communities that need our help the most, encourage more people to apply, and protect them from being evicted.”

4 thoughts on “Here’s What the Supreme Court’s Latest Eviction Ruling Means for NYC”

Was the federal eviction freeze really “designed to keep tenants housed in places with high rates of COVID-19”?

No

The Supreme Court’s common sense ruling affirms the simple fact that no government entity can force a property owner to provide free housing. Homeowners, even owners of 1-family homes, should be rejoicing today. Its up to congress now, but any law they write must adhere to the very clear Constitutional provisions protecting private property rights, otherwise the SC will toss it too. You think the liberals are howling today, just wait till the SC dismantles NYS’s and NYC’s renter protection and rent stabilization laws. Both are ‘takings’.

It’s true they need to get the funds out more quickly, but the property owners don’t have a real complaint if taxpayers are making them whole by paying tenants’ missed rent and saving them eviction expenses. Would they rather take the loss of income and court costs?