Photo Courtesy of Noel Woodford

Helen Taylor recites an original poem during Fortune’s Arts Festival at MoMA PS1 in April.The first time Helen Taylor read a poem at a writer’s workshop, many of her classmates began to tear up.

Taylor is an artist and a formerly incarcerated person, having served 18 months on Rikers Island. For many years, she doubted her creative abilities. But through art programs offered by groups like The Fortune Society, a city-based nonprofit that runs reentry and alternative criminal justice services, Taylor said she’s been able to express herself in ways that originally scared her.

“It gives us a positive way to approach life after looking at it and dealing with it for so long in an ugly manner,” she said. “I get the opportunity to get rid of some garbage that I needed to get rid of through acting, through putting it on paper or doing a simple drawing. Things that I wasn’t able to talk about, I can through arts.”

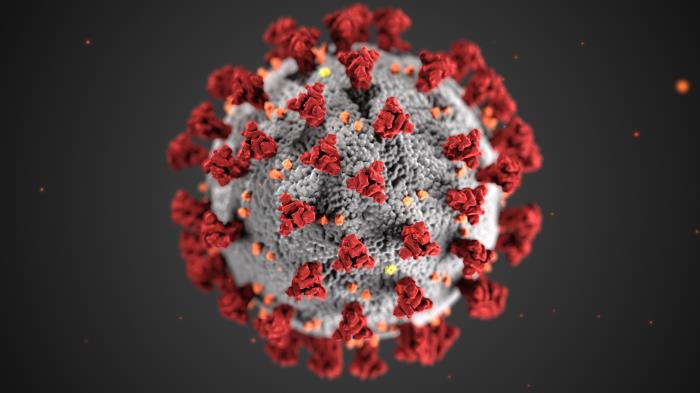

Experts and advocates have long touted the beneficial role of arts programs in the criminal justice system, both as an outlet for incarcerated people to express themselves while behind bars and an important element of the rehabilitation process once they’re released. And while the COVID-19 pandemic may have limited the intimacy of prison and reentry arts programs, many found ways to continue to teach, appreciate and showcase the work of incarcerated artists even during the crisis, by transitioning to virtual and solo lessons.

“Art is not frivolous,” said Joe Giardina, program director at Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA), a nonprofit that runs art programs at six New York State correctional facilities and recently resumed its in-person programs again after a year of virtual services.

“Being incarcerated is a traumatic experience, and there are not too many safe spaces,” he added. “The arts does that.”

‘It’s anything I want’

Prisons were some of the worst places to be during the height of the pandemic. While clemency was provided for some, the virus ravaged detention facilities across the state: DOCCS has recorded roughly 12,000 positive COVID results and 52 deaths among staff, the incarcerated population and parolees since last year.

For many behind bars, art remained an important outlet that allowed them to express their feelings on the impact of the pandemic, and draw attention to their plight. In May 2020, local advocacy organizations The Confined Arts and Releasing Aging People from Prison presented “Open Call for Clemency,” a virtual exhibit featuring the works of incarcerated artists that “reflect on personal responses to the current COVID-19 pandemic.”

The exhibit was also a form of activism: The presented works, which included paintings, sketches and poetry, were intended to “emphasize the humanity of those who are incarcerated” and specifically urged governors across the country to release the most vulnerable inmates from lockup, to stop the spread of the virus.

Pastor Isaac Scott, who founded the Confined Arts at the Columbia University Center for Justice, said the group’s work and outreach actually expanded during the pandemic since everything went virtual.

“It’s kind of bittersweet, but you can actually do more work when everyone is Zooming,” he said. “It was easier to reach across state lines to get to people. We’ve been able to collaborate with artists all across the country.”

Rehabilitation Through the Arts also went virtual throughout the pandemic, offering classes that were either pre-recorded or led over email instructions. Still, Giardina said the classes went well, and participants remained engaged, using their experiences of the crisis to inform their work.

“We sent out an email just to see how everyone was doing, and this was relatively early in the pandemic,” he said. “The response we got from our members was incredible, telling us how they were dealing with COVID, and we decided to use some of that writing to create a virtual performance.”

Art can also help break up the monotony of life behind bars, and provide people in prison with a sense of autonomy that incarceration takes away. One of the building blocks of the system is a lack of variety; life in prison is purposely rigid and structured.

“After spending more than a decade in the system, I can tell you that the choices we have become ultra-limited, and the way we think becomes ultra-limited,” said Brett Gonzalez, a painter and assemblage artist currently serving time in the Federal Medical Center in Fort Worth, Texas. He’s also the first incarcerated board member of the Justice Arts Coalition, a national nonprofit group that provides resources to artists in the prison system.

“Today for lunch, I had a hamburger. I’ve had a hamburger for lunch every Wednesday for almost 11 years. I’ll continue to have a hamburger every Wednesday,” Gonzalez said. “But when I sit in front of a piece of paper or a canvas, it’s anything I want.”

One of the most important benefits of offering creative outlets in prison, he added, is the sense of value inmates get, even if it’s just from showing their work to each other or a family member.

Gonzalez never considered himself an artist before serving time; he used to work in the IT industry. But once he was incarcerated, he constantly thought about his past mistakes and the harm he caused. A friend suggested he try processing those thoughts through art.

“I think one of the true root causes of crime is a lack of empathy and being able to understand things from other peoples’ points of view,” Gonzalez said. “The prison system definitely does not help develop that. Art allows me to look internally.”

‘I never felt like I belonged anywhere’

Those social and emotional skills that arts programs help foster are essential to rehabilitation and successful re-entry, advocates and experts say.

Rehabilitation Through the Arts’ approach is not just to make people better dancers, writers or painters, but to teach life lessons through a creative medium: Dancing helps members challenge gender stereotypes, visual art improves observation, and improvisational acting teaches you how to make decisions under pressure.

“It truly is part of education,” Giardina said. Through contracts with the state DOCCS, RTA currently runs programs at the Bedford Hills, Fishkill, Green Haven, Sing Sing, Taconic and Woodbourne correctional facilities, with 200 members who must each commit to two arts workshops per year, lasting 12 weeks. The organization boasts that less than 5 percent of its members return to prison, a stark contrast to the national recidivism rate, which is closer to 60 percent.

According to a 2011 study from the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, RTA members at Sing Sing were also shown to have significantly lower rates and severity of infractions compared to those who didn’t participate in the arts program. The study suggests the corresponding decrease in infractions among RTA members could likely be because they were busy rehearsing for a play and didn’t have the time or opportunity to get in trouble. However, it also suggests that art has innate positive effects on people’s attitudes.

“You can express yourself in a way you aren’t normally allowed to in a carceral setting. What a lot of the men and women say is that it’s a place where they can take off the mask and be who they truly are,” Giardina said.

It has an important role in reentry, too, advocates say. Earlier this month, The Fortune Society hosted its first “We Choose to Bloom” virtual arts festival. It included a film, created in partnership with MoMA PS1, in which 24 Fortune Society artists performed music, poetry and spoken word pieces as part of Rashid Johnson’s art installation “Stage.”

The installation, which is minimal and fitted with five microphones of varying heights, is an homage to sites like Speaker’s Corners in London’s Hyde Park and Harlem’s 135th Street and Lenox Avenue—places where the public can step up to the mic and freely speak their minds.

After a preview screening of the film, Fortune Society founder David Rothenberg said it was a cathartic moment for many.

“One kid—he was the youngest in the group—and he told me, ‘I never felt like I belonged anywhere before,’” Rothenberg said. “There was a woman in her 60s who cried when she saw herself in the movie. She said, ‘I’ve never been part of anything positive before.’”

With vaccines now readily available in New York, some organizations are resuming in-person arts initiatives, like The Confined Arts, which is planning a play at the Auburn Correctional Facility and the Newark Public Arts Project, where community members will create a public art installation and film addressing racist tactics associated with the war on drugs.

“This is the role of the arts: We’ve got to imagine a world where we don’t rely on prison. Right now, this nation is very reliant on prison,” Scott said.

“We don’t have a different way of dealing with the ills of society. We need to begin to imagine those things and see them on film and read them in fiction. We need a starting point,” he added. “The arts are going to be the way we get to quicker policy changes and more just laws.”

2 thoughts on “NY Prison Arts and Reentry Programs Persist Throughout Pandemic”

Excellent, true words has been written. Thanks to all whom has spoken the enjoyment of art. Grateful for the Fortune Society.

Their poem is just outclass, writer workshop department is working fine job. Well, https://theresearchguardian.com/ talking about their 18 months on Riker Island where they only focusing on the job that assigned.