Lind Family

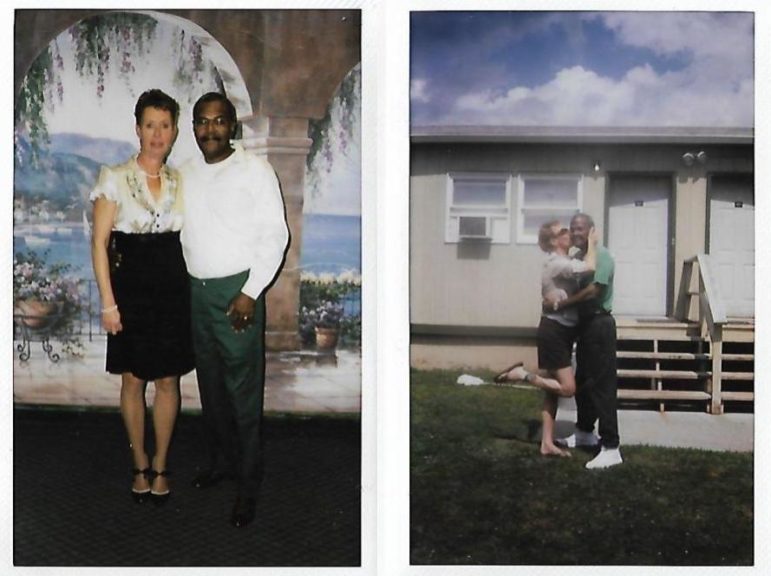

Michelle and Robert LindMost mornings, Michelle Lind turns on the TV in her Kingston, New York, home to watch Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s pandemic briefing, hoping he will say something about granting clemency to incarcerated people who are elderly and at high risk for COVID-19.

The rest of the day, she hovers by the phone, anxiously waiting for a call from the Sullivan Correctional Facility in Fallsburg, New York, where her husband, Robert, 73, has been incarcerated for decades after a shootout with police in Washington Heights.

For many years, groups like Release Aging People in Prison, a nonprofit clemency campaign, have been fighting for the release of older prisoners—people who had served decades, posed no threat to public safety and were likely to soon need expensive medical care—if they didn’t already. The pandemic has turned up the volume on those calls.

According to the campaign, 78 percent of incarcerated people who died in New York since March 30 were older —aged 55 and up. Advocates want to hold down those numbers through the early release of people who are at high risk for the virus. Lind is one of them.

“He has maybe five good years left for God’s sake. Let him come home and just sit on the couch with me for five years,” Michelle said, 61, who has not seen her husband since November. “Let him come home now and we can sit here and be scared together, because at least we’re not alone.”

No clemencies yet

While the governor acknowledges the danger in nursing homes during the coronavirus pandemic, families like the Linds feel that Cuomo has forgotten about the elderly in the prison system who are unable to social distance. There are 10,000 people in the prison system over the age of 50, according to the New York state Department of Corrections and Community Supervision.

More than 1,200 corrections officers have tested positive in the state corrections system, including one in Robert’s block last month. At least 450 incarcerated men and women have tested positive. Sixteen have died.

“I stay in the cell during the day to stay away from other people. I read. And now, I’m walking around looking like a bandit,” Robert he told me via email before he was struck by the virus.

Cuomo has ordered the release of over a thousand parole violators—most of them held in local jails—in response to coronavirus concerns, but no clemencies have been granted in response to the pandemic. Meanwhile, governors in California, Vermont, Kentucky, Maine and Wisconsin, which have lower rates of COVID, have already begun granted clemency. In Vermont, the prison population was reduced by almost 12 percent between the months of January and March. New York City jails have shed more than a fifth of their inmates.

A shooting, a sentence, then sickness

In 1983, Robert—who’d previously served two prison stints for robbery—was sentenced to 50 years-to-life for attempted murder after a shootout with police in Washington Heights. No officer was hurt. Sentencing for attempted murder has a minimum of 20 years in New York, with sentences ranging longer when a police officer is involved. After 36 years in prison, Robert’s earliest release date is 2032.

In many ways, Robert, who recently underwent chemotherapy for prostate cancer, has had an exemplary record in incarceration. He has run an orientation program for men who are new to the Sullivan Correctional Facility, and a nonviolence program at the Shawangunk Correctional Facility in Wallkill, New York, that was ultimately adopted by other correctional facilities throughout the state.

“I emphasize that, ‘We all have to leave here smarter than when we came in,’” Robert said. “And that we were not born here, therefore, we have no business dying here.”

Jose Saldana, the director of the Release Aging People from Prison campaign, calls Robert a prison icon—and occasionally “Grandpa.”

“It was a comprehensive approach to teach the new guys how to let time serve you, as opposed to you serving time,” Saldana, who was incarcerated with Robert before being released, said of the program Lind started. “We’re trying to help so that they don’t languish in prison for decades the way we did.”

A clemency bid

In 2015, Robert received a letter from President Obama for his work and a paper he wrote about the elderly in state prisons. When Robert applied for clemency in 2016, he included that letter and other recognitions to support his application. Not much has happened since.

“On Jan. 3, 2017, I received a letter from director Donald D. Fries which was dated Dec. 27, 2016,” he said. “It said, ‘Once an attorney has accepted your clemency application case, your attorney will notify you in writing of the case assignment.’”

That was the last time Robert heard from the Executive Clemency Bureau, and Director Fries has since retired. As each day passes with no news about clemency from the governor, Michelle loses hope.

“I’m trying to save my husband’s life and I feel like I’m failing because he’s just not budging,” she said. “I’m not asking you to release the whole elderly population, just take your time and look— just for a week.”

Robert has more faith.

“Maybe he’s not going to say anything,” Robert said in March about Cuomo. “Maybe he’s just going to do it.”

Talking daily

Michelle and Robert Lind never used to talk every day, but as the COVID-19 became more of a threat, they began talking on the phone daily around 6:30 p.m. – just make sure, they said, that the other was still breathing.

By 5 p.m. on those days Michelle, who suffers from depression as well as a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, was struggling to breathe. She took the anxiety medicine her daughter, Whitney Jones, left on her porch.

Before he was hospitalized with the virus, Jones said her mother and Robert were intent on shielding each other. “He doesn’t want her to worry, so it’s a whole mess of worry when everybody’s trying to prevent the other from worrying,” she said.

Michelle wouldn’t tell him that some days she can’t convince herself to shower. He wouldn’t tell her how afraid he was.

“He won’t say, ‘Oh, honey, I’m sick.’ Or, ‘Oh honey, I don’t feel good,’” Jones said. “He’ll just suffer.”

When Robert told Michelle that he had prostate cancer two years ago, he called it, “just a little bad news.” It took a year, Michelle said, before he had an outside trip to a doctor. Another six months passed before doctors did imaging and found two tumors. Then this February, Robert completed four weeks of chemotherapy for prostate cancer.

“Which isn’t bad, for the [prison] system,” Michelle, 61, added.

A lack of information

Robert was supposed to return to his doctor for bloodwork in March, but coronavirus—and a nitrogen leak at the medical facility—prevented that. Robert took the two-hour trip to Albany Medical Center with 15 other inmates from other facilities. There, they sat in a bullpen, some without masks, and waited for two hours before a correctional officer came.

“He said, ‘We’re sorry. Your appointments were canceled because we have a nitrogen leak in one of the tanks outside,” Robert told Michelle later that day. “Here’s a bag lunch.”

From home, Michelle seethed, afraid to go outside herself and acutely aware of the how exposed her husband was.

“This is just not fair, and to sit here and know that any day this phone won’t ring and that means they taken him and I’ll lose him,” Michelle said. “I know I won’t be able to find him; they won’t give me any information on him.”

On May 1, Robert wrote, “A Cuban dude that I know from B-North was tested and came back positive. He is down in the infirmary. The two guys who locked on each side of him, they just brought to this block to lock upstairs.”

On May 12, Robert didn’t call. The nursing staff at Sullivan called Michelle the next day. Robert had coronavirus and pneumonia and was sent to Catskill Regional Medical Center. Michelle was not able to find out whether he had access to a ventilator or not.

According to the Release Aging People in Prison campaign, there are over 6,000 clemency applications in the State of New York waiting to be considered. Cuomo has granted 11 since January 2020; two were for people in prison, and the balance were already free but faced immigration consequences for past convictions.

10 thoughts on “He was Waiting for Clemency. Now He’s Fighting Coronavirus.”

Sad story you have my condolences but this story however is all to familiar my sister,my friend I lost her on 4.28 .due to the covid 19 she was a 61yr.old female from Buffalo ny..almost made it out on medical parole but was very sick and stricken due to the virus how many people do we have to loose before Cuomo steps up and say something …. Cuomo we are waiting on you …long live lulu ..justice for all justice for Darlene Benson Seay..lulu

Why they only release a rich people even if they commit the same crime of the others prisoners is not fear for everyone😡🥵😡🥵

NYS prison system is predicated on perpetual punishment say that 40k times- for each person being held hostage and has the propensity to serve a death sentence. Our loved ones were not sentenced to death. Our hearts are breaking because Criminally impacted people’s lives matter. Examine the individuals own rehabilitation and based on this, use your executive power to break the generational curse of “If you didn’t do it, one of your kind did” you can go peacefully to jail or we damn you to hell. As people of color that is our option even in tge new millennium. Say their names, they’re killing us inside and outside- literally

Governor Cuomo, please release these men and women who are fifty years of age and older who have a great prison record, and deserve to live productive lives in society. Taxpayers money is wasted keeping older people in prison. Act in the name of truth and justice to release people from prison who deserve to come back to society. Thank you.

Gov. Cuomo, please release old people from prisons.

Finish out your sentence….if you are eligible for parole go through the process….please don’t let Covid blindly release prisoners until they have paid their price to society and gone through the traditional steps. If you don’t want to be in prison during these times or future bad times, please do not commit the crimes.

What’s the update on Robert Lind? How is he doing?

What’s the update on Robert Lind?

What’s thevupdate on Robert lind?

I pray for Michelle each day. Robert is in my prayers also. Love you both.