He’s raised big money from real estate, advocated for lots of development, and approved the majority of development deals he’s considered—with a few important exceptions.

Adi Talwar

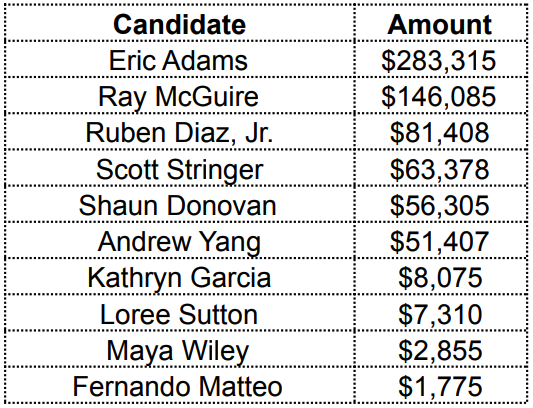

Mayoral Candidate Eric Adams in the South Bronx on a mid-April afternoon.Eric Adams has received more campaign contributions from the real-estate sector than any other candidate for mayor. The Brooklyn borough president has booked at least $283,000 from donors who identified themselves as working in real estate, construction, land development or property management—nearly twice as much as financier Ray McGuire, the next biggest recipient of real-estate generosity, and more than five times as much as frontrunner Andrew Yang.

It’s tempting to follow that money and conclude that Adams is the candidate of developers. As The City has reported, Adams has hauled in big real-estate bucks throughout his career. But he’s also the borough president who stood against the de Blasio administration’s development agenda in East New York, and broke with allies over the Bedford Armory. Throughout his time in borough hall he has sent conflicting signals about his approach—declaring a pro-development desire to “build, baby, build” early in his tenure, then making headlines last year for telling gentrifiers to “go back to Iowa.”

“I’d say he’s been pretty balanced,” between the desires of developers and community concerns, says one Brooklyn housing advocate. But it’s unclear whether that reflects a consistent yet nuanced philosophy or an episodic approach. “He’s a bit of an enigma,” the advocate adds.

A complex backstory

Adams has always displayed some philosophical and personal nimbleness. As a vocal leader of Black police officers in the 90s, he served as an “escort” for Mike Tyson when the disgraced heavyweight was released from prison after doing time for a rape conviction, but also railed against violent television and graphic rap lyrics. He ran for Congress in 1994 as a Democratic supporter of Louis Farrakhan, but by 1999 was describing himself as a conservative Republican. He’s now an advocate for a plant-based diet who has vowed to carry his NYPD retiree firearm if he’s elected mayor, making him perhaps the most heavily-armed vegan in America.

Of the top eight candidates in the Democratic primary, not to mention the two main Republicans running for mayor, Adams is one of only two who have ever won elected office. However, unlike Scott Stringer, a former Assemblyman who prevailed in a nasty 2005 primary for Manhattan borough president and beat a former governor to become comptroller in 2013, Adams has never faced a competitive election. He won his first State Senate primary with 78 percent of the vote, and has never had to run against a Democrat since. In his two general elections for borough president, he won with 91 percent and 83 percent of the vote.

Adams spent most of his seven years in the State Senate in the minority, during which it was all but impossible for a Democrat to get bills passed. During the brief period of Democratic control in 2009 and 2010, Adams passed bills that barred police agencies from imposing quotas on how many tickets or summonses officers issued, limited the data cops could retain after a street stop, and expanded housing preferences for veterans. He was part of a group of senators who pushed for tenant-friendly rent reforms in 2009, but in a speech to real-estate lobbyists he chided them for not doing more to create bonds with Democrats. “Because you failed to nurture the relationships, you found yourself out of the conversation,” he was quoted by Crain’s as saying in ’09. “How many of you made investments in the Democrats when we were two seats away [from controlling the Senate]?”

The Albany years gave Adams a chance to demonstrate his principles—he gave a passionate speech supporting gay marriage during the failed 2009 attempt to overturn New York’s ban on the practice—but they also generated one great blemish on Adams’ reputation: A 2010 report by the state inspector general about the controversial selection of a politically-connected company as the winning bidder for the “racino” franchise at the Aqueduct racetrack. The report declared some of Adams’ testimony to be “incredible” and scorched his admission that he hadn’t bothered to read detailed memos about the bidders before making his recommendation. The IG chided, “[I]t seems reasonable to expect the Chairman of the Racing and Wagering Committee in the Senate to actually review all proffered information thoroughly before recommending a vendor for a 30-year contract that meant billions of dollars to New York State.”

Adams has not been immune from subsequent questions about the rules. Earlier in his tenure as BP, Adams was faulted by the city’s Department of Investigation twice, once for violating rules governing the solicitation of donations for his One Brooklyn nonprofit and again for charging city agencies to use borough hall.

Adi Talwar

Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams at a campaign event in the Bronx in April 2021.The housing record

As borough president, Adams lacks significant policymaking authority but he does play a prominent—though only advisory—role in the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure that the city uses to shape and enact changes to zoning and other policies.

Adams’ land-use director, Richard Bearak, has held that post since 1993; Adams is the third borough president he has worked for. While Adams’ direct predecessor, Marty Markowitz, was an irrepressible cheerleader for development, Adams has been harder to peg.

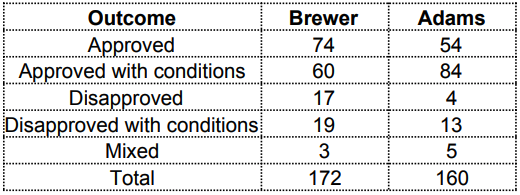

Of the 160 land-use applications on which he has rendered a decision since becoming “beep” in 2014, Adams has approved 86 percent (most of them were conditional approvals). By comparison, Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer approved 78 percent.

ULURP Outcomes

Borough President Recommendations, 2014-present

Some of those decisions drew more attention than others. Adams conditionally disapproved the 2015 East New York rezoning, issuing a long list of demands including 100 percent affordable housing at some sites, enhanced tenant protections and provisions to help local businesses. A member of the coalition that opposed that rezoning said Adams met with the group several times and that his state objections included both the coalition’s priorities and his own.

Five years later he went against the local community board by approving the bulk of the Industry City expansion plan, despite concerns about the project’s potential for displacement and gentrification in Sunset Park.

On other development issues, Adams has been fairly quiet. He does not appear to have been a big player in either of the major community planning processes that occurred in the borough during his presidency, Bridging Gowanus and the Bushwick Community Plan. When the City Council held a hearing on the landmark—and very contentious—Mandatory Inclusionary Housing program in 2015, the Manhattan and Queens borough presidents testified and the Bronx BP submitted testimony but Adams did not; he did vote earlier to oppose the measure when the Brooklyn Borough Board considered it.

During the mayoral campaign, Adams has pointed to his Building by Faith initiative, which aimed to get the borough’s religious institutions more involved in affordable housing. “We don’t do that enough. They don’t build for profit, they build for people,” he told a February forum. “I think that’s the first place we can go.” According to borough hall, the Building by Faith initiative has spent $5.5 million on projects that included some 987 units of affordable housing at five sites—although other city subsidy programs were involved in at least some of the projects.

A call for coordination

Adams’ mayoral platform is rooted in a book of 100 brief ideas—a mix of huge promises (e.g., his 68-word plan to make New York City the “life sciences capital of the world”), solid ideas (e.g. universal dyslexia screening) and small ball (e.g. a proposal to use drones to do building inspections).

When he has a chance to state the rationale for his candidacy, Adams typically argues that the city suffers not so much from a lack of resources or faulty policies but rather a lack of data and coordination. “By combining all agency metrics onto a single platform similar to CompStat and using analytics to track performance in real time, we can go from a reactive approach to city management to being proactive and, eventually, predictive. The cost savings and improved performance will save billions of dollars and deliver far better services to New Yorkers,” his platform reads.

At a March 11 NY1 forum on housing, Adams again sounded his support for “a better coordination of services within all of our agencies” and “de-silo-ing our city.” “We have to take the guessing game out of government. We exist in silos. There’s no coordinated efforts,” he said. “We need mission-driven agencies.”

But, when it comes to housing, what’s the mission for which Adams wants better coordination? Stringer’s housing plan is 47 pages long. Shaun Donovan’s runs nearly 9,700 words. Kathryn Garcia, McGuire, Dianne Morales, Maya Wiley and Yang all have stand-alone housing plans, some of them offering a fair amount of detail.

Adams is among the candidates speaking in broader terms. His housing agenda—like the rest of his platform—is primarily presented within his “100 ideas” book. Its central tenet is a promise to build new housing “in wealthier areas with a high quality of life, allowing lower-and middle-income New Yorkers to move in by adding affordable housing.”

He also calls for repurposing city offices, private office buildings and hotels for housing, changing building codes to permit the construction of micro-apartments, increasing the value of rent subsidies and making it easier for New Yorkers to access rent relief. Adams also endorses giving more power to community development corporations, deeding public land to community land trusts, facilitating live-work developments and selling air rights over NYCHA developments to generate more cash for public housing.

A cop on the case

Throughout the de Blasio era, there has been intense debate over whether the solution to the city’s housing crisis is an increase in supply—both market-rate and subsidized-apartments—or efforts to make the existing housing supply affordable to low-income New Yorkers. The amount of attention de Blasio’s housing plan devoted to moderate- and middle-income households struck some as a waste of resources, especially since data showed middle-income families faring far better in the private market. Some lotteries for affordable middle-income units struggled to find willing applicants.

If there’s a consensus now, it’s that New York City can neither freeze construction of new buildings nor build its way out of the crisis: The city needs new housing, but merely adding more apartments won’t necessarily ease rent burdens.

Like all the other major candidates, Adams has signed on to the United for Housing plan, which among others things calls for a $4 billion annual capital investment in housing—double what the de Blasio administration has spent. That commitment is in line with Adams’ aggressive, pro-development agenda. But Adams’ sketch of a housing plan leaves big questions. Will community input play any role in determining how and where housing is constructed? Will infrastructure be aligned to absorb the new density? And, most important, which income groups will these new units primarily be targeted for?

Adams has certainly demonstrated concern for the city’s poorest. He risked political backlash in Brooklyn in 2017 by supporting the establishment of a homeless shelter in Crown Heights over objections from local residents who felt the area had been over-saturated with social-service facilities, and he has pointed during his campaign to his efforts to create partnerships between shelters and communities in places like Kensington. In explaining this work, Adams has discussed his own childhood in a very low-income household.

But as a mayoral candidate he has also expressed a lot of concern for middle-class housing needs. At the NY1 forum Adams rebuffed tenant advocates who had been pushing for a cancellation of rent, pointing to the needs of small landlords in communities of color. “We will see the greatest devastation of Black and brown wealth if we cancel rent” without relief for landlords, he said, and later added, “We have decimated the middle-income groups and we have left them alone.” He evaded follow-up questions about exactly what income level means “middle class” to him.

Adams’ campaign literature says merely that his housing will serve “all who need it,” or that he will “add housing – for everyone.” Some of his rivals have been much more specific. Garcia promises “50,000 units of deeply affordable housing” for families with incomes less than 50 percent of Area Median Income. Stringer says he’d prioritize “low and extremely low-income New Yorkers, such as families of three making $58,000 a year, or two parents making minimum wage.” McGuire also offers some income-group targets.

As a borough president, Adams has been able to react to the housing and development schemes that others proposed. At least one fellow pol has found those episodes revealing. “I think he’s cautious,” the pol said. “He’s been incredibly cautious. Trying to see how the winds are shifting. It’s all on a case-by-case basis. That’s his training as a detective, and his training as an officer. He was asking questions. He was trying to understand, just as a cop would if he were building a case.”

After seven years of Bill de Blasio, who promised a “transformative” mayoralty but only managed to piss just about everyone off, there is something attractive about a gumshoe mayor, taking one problem or one project at a time and solving it. But a mayor does more than solve problems, and she or he cannot simply react: One way or another, a mayor imprints a vision on the city, especially on its physical face. The stature Adams has achieved over 30 years of public life counts for a lot, but it doesn’t fill in all the gaps in his housing vision.

Those gaps haven’t dissuaded real estate from giving big to his campaign. Among the top companies donating to Adams are Gravity Construction, whose employees have donated $14,250 to his cause, Potsdam Specialist Properties ($6,500) and Two Trees Management ($6,400). Jed Walentas, an executive at Two Trees, is Adams’ No. 2 intermediary, having raised $5,100 for him so far. The borough president’s top bundler, former Congressman Ed Towns, has raised $6,900 for Adams. According to city lobbying records, Towns from 2016 through 2019 only registered for one client: Arker Diversified Companies, a major affordable-housing developer.

Real-Estate Fundraising

Top 10 mayoral candidates ranked by total contributions coming from donors who identified as working in realty, real-estate development, property management or construction occupations or employers

2 thoughts on “‘He’s a Bit of an Enigma’: What Eric Adams’ Development Record & Housing Plan Tell Us”

…making headlines last year for telling gentrifiers to “go back to Iowa.”…’

His none too subtle hint that he wants the whites (really the white ethnics) out of the city.

Using drones for building inspections isn’t “small ball” . It is a potentially meaningful cost-saver with no detriment in quality. Currently, buildings are required to have an engineer complete facade inspections under Local Law 11 every three years, by direct sight–no binoculars–which means that buildings must erect scaffolding, or arrange for drop scaffolding if feasible, and secure all the necessary permits. Permits are time consuming to obtain, and the whole process can easily run five figures, which is an unnecessary expense–borne equally by affordable and market rate housing. These inspections could and should be easily and inexpensively be conducted via drone. City Limits should be advocating for the adoption of this and similar simple innovations, not dismissing them as “small ball” .