The city’s Health Department has been monitoring a number of sources for potential communicable diseases outbreaks for more than 20 years. Here are some of the illnesses, other than COVID-19, that have seen recent upticks in New York.

NIAID

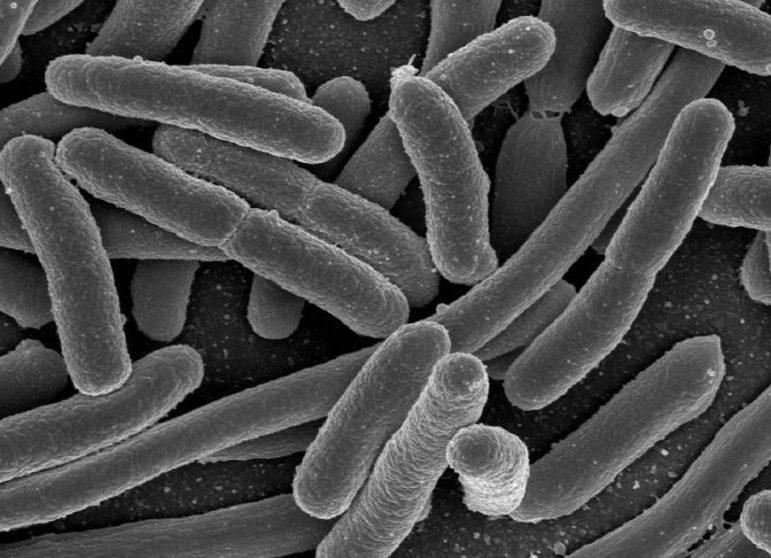

A microscopic look at Escherichia coli. The Shiga toxin-producing variety is one of several diseases New York health officials track regularly that has seen big increases in recent years.This story was produced through the City Limits Accountability Reporting Initiative For Youth (CLARIFY ), City Limits’ paid training program for aspiring public-interest journalists.

On Monday, during a press briefing about the state’s ongoing response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Gov. Andrew Cuomo slammed the federal government for not doing more to monitor and prepare the country during the early stages of the outbreak, as it was ravaging populations in China and Italy.

“You think the virus was going to sit there in China and wait for you?” Cuomo asked rhetorically. “It went to Europe in January, in February, and then it got on a plane and it came to New York. You know where the European flights come? They come to New York.”

COVID-19 did, indeed, come to New York, as do dozens of other infectious diseases each year. As a major urban crossroads, home to three major regional airports and tens of millions tourists annually, the city is no stranger to communicable illness—while coronavirus may be the deadliest and most disruptive one in recent memory, it’s got plenty of company.

“New York City is a major business location, tourist location, family location, for people all over,” says Marjorie P. Pollack, an infectious disease epidemiologist based in the city. “All the major cities are recognized as high risk of communicable diseases.”

That makes disease surveillance especially important for a city like New York, says Pollack, deputy editor at the Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases or ProMED, a massive global online service with more than 86,000 subscribers that scans for and shares reports of potential disease outbreaks.

“We need to be keeping our fingers on the pulse of everything going on,” she says, a colossal task that requires the monitoring of numerous data and public health alerts with an eye on “that first needle in the haystack,” that could indicate a possible pandemic.

New York City has its own monitoring system, called the Syndromic Surveillance System, which first developed in the mid-90s to detect outbreaks of waterborne illness, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Following the Sept. 11 attacks and increased fears of bioterrorism, the system later began tracking data from emergency departments across the five boroughs, looking for clusters or upticks in specific symptoms—such as respiratory problems or diarrhea—which could mark trouble. The system also monitors data relating to ambulance dispatch calls and worker absenteeism, according to the CDC, as well as pharmacy sales—tracking a portion of both over-the-counter purchases and prescriptions for increased use of things like analgesics, anti-diarrheal, cold and flu and anti-allergy medications.

“There’s a long history of infectious diseases in New York City, and the Health Department has grown with it,” says Stephen Morse, an infectious disease epidemiologist and one of ProMED’s founders. “It’s taken us a long time to learn how to do this well.”

Disease surveillance also largely depends on doctors and other public health workers reporting unusual incidents and confirmed cases of communicable diseases to the authorities. This was the case with the first reported North American outbreak of West Nile virus, the mosquito-borne disease which was detected in New York City in 1999 after health workers noticed a cluster of encephalitis cases in Queens.

“That’s how it was found—by a cluster of cases that somebody reported, that proverbial astute clinician,” Morse says.

The city’s Health Code classifies dozens of illnesses as “reportable,” meaning health care providers are required to notify the government of confirmed or suspected cases. Some—such as measles, rabies, Zika virus and Hepatitis A—must be reported to the Health Department immediately, and others must be reported within 24 hours.

The city publishes annual data on communicable diseases through its EpiQuery database. Of these illnesses, influenza saw the highest number of cases in 2018—the most recent year for which data is available—with more than 52,000 infections across the city, more than double that of the year before.

Other diseases that appeared in large numbers include respiratory syncytial virus, which causes mild cold-like symptoms for most people but can be more serious for infants or older adults, and which saw nearly 16,000 cases in 2018. That year also saw more than 2,000 cases of campylobacteriosis, a common bacterial infection, usually contracted from undercooked food, that causes symptoms like diarrhea and stomach cramping. Those ailments saw upticks of 54 percent and 126 percent over the past five years, respectively.

The presence of other communicable illnesses have decreased. In 2013, there where 139 cases of dengue virus, a mosquito-borne disease that causes flu-like symptoms; that number dropped to 22 cases in 2018, down from 32 the year prior. Zika virus, of which there were 987 cases in the city in 2016—part of a global outbreak that year—dipped to just 19 infections in 2018.

In the chart below, City Limits compiled data for a dozen reportable infectious diseases in which there were more than 50 cases in 2018, and which also saw at least a 25 percent increase during both the most recent one- and five-year periods.

Health experts say one of the most vital components of effective surveillance is adequate funding for disease research, so scientists can understand and better predict how illnesses will behave as they evolve or develop resistance to certain treatments.

“Bacteria and viruses are smart,” says William R. Jacobs, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine. “So we have to be vigilant.”

| Disease Name | Description (Source: CDC) | 2018 Cases | 5-Year % Increase | 1-Year % Increase | Neighborhood With Highest 2018 Cases |

| Campylobacteriosis | The main cause of bacterial diarrheal illness in the U.S., often contracted by eating certain foods like undercooked chicken, or drinking untreated water. | 2,664 | 54% | 26% | West Queens (194 cases) |

| Cryptosporidiosis | A parasite-borne illness that causes diarrhea, cramps, vomiting and other flu-like symptoms. | 250 | 213% | 53% | Greenpoint (19 cases) |

| Cyclosporiasis | An intestinal illness contracted by consuming food or water contaminated with the parasite. | 87 | 480% | 47% | Upper West Side (9 cases) |

| Haemophilus influenzae (invasive) | A bacteria that can cause a range of infections, from mild ailments like ear infections to more serious ones, like meningitis. | 153 | 44% | 30% | Pelham/Throgs Neck (9 cases) and Western Queens (9 cases) |

| Influenza | A contagious respiratory illness that can be spread from person to person, with symptoms that include fever, cough and sore throat. | 52,412 | 364% | 128% | West Queens (3,067 cases) |

| Legionellosis (Legionaire’s disease) | A lung infection transmitted by breathing in small droplets of water that contain the bacteria, causing symptoms such as muscle ache and shortness of breath. | 656 | 118% | 51% | Washington Heights/Inwood (62 cases) |

| Meningitis, bacterial | A bacterial infection most commonly spread from person to person which can cause serious illness and even death. | 232 | 58% | 20% | Borough Park (26 cases) |

| Norovirus | An extremely contagious virus contracted from an infected person, or through contaminated food or drink, which causes vomiting and diarrhea. | 1,394 | 1352% | 64% | Washington Heights/Inwood (110 cases) |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | A common respiratory illness that usually causes cold-like symptoms, but can be more serious for infants or older adults. | 15,918 | 126% | 83% | Borough Park (1,104 cases) |

| Rotavirus | A virus that causes diarrhea and severe vomitting in infants and children. | 448 | 159% | 30% | West Queens (43 cases) |

| Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli | A bacteria commonly associated with foodborne outbreaks, causing diarrhea and severe vomiting. | 504 | 466% | 338% | Upper East Side (32 cases) |

| Shigellosis | A group of bacteria causing diarrhea, fever, and stomach cramps. | 983 | 210% | 115% | Borough Park (91 cases) |

3 thoughts on “The Other Communicable Diseases —Besides Coronavirus—That Call NYC Home”

super informative. good job youth writers!!!!

really good work–excellent!

Very insightful read! Astute reporting, and helpful data