George Floyd’s death last week at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer exposed some of the continuing fault lines between the police and the community, and the lack of confidence that the police do indeed work on behalf of all the people they are sworn to serve. One significant factor engendering this absence of trust is the lack of transparency over police operations and specifically, over the process of police officer discipline.

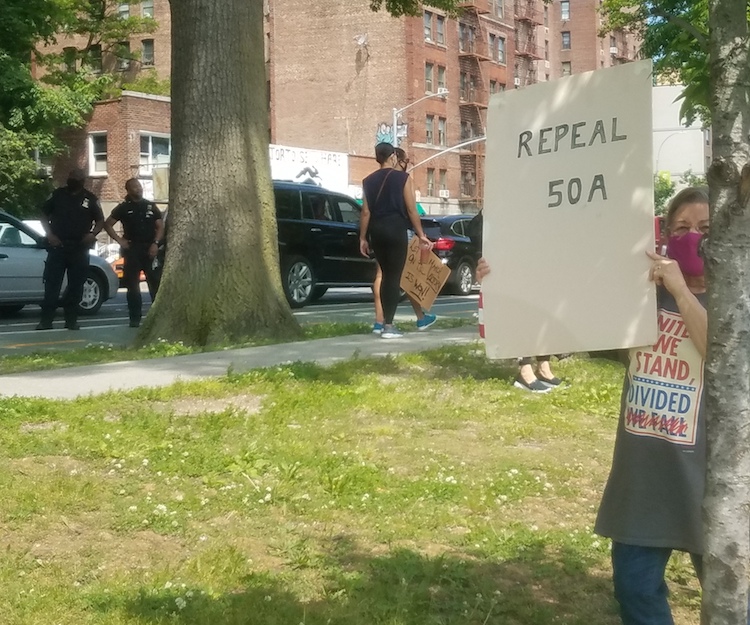

Thus, it was encouraging to see Governor Andrew Cuomo quoted this past weekend as saying that he would immediately sign into law any bill that the legislature passed this session repealing Section 50-a of the New York State Civil Rights Law, the section which prohibits the New York Police Department (NYPD) from releasing to the public details about a police officer’s disciplinary record. Such a bill, repealing Section 50-a, has languished in legislative committee for the past two sessions, so clearly any push from the governor is needed in order to secure the bill’s passage into law.

It was even more encouraging to see Mayor Bill de Blasio quoted as being in favor of repealing Section 50-a, although his “wish we could get Albany to act [on repealing the bill]” revealed either a finely tuned sense of irony or a misapprehension as to the role any New York City mayor should play in securing a major piece of legislation.

Be that as it may, as someone who has argued for repeal of Section 50-a for more than a dozen years, such stirrings of activity to increase transparency as to the workings of the NYPD is most welcome. But, then, of course, repealing Section 50-a is the easy part; the hard part will be in creating a new system that ensures police officer discipline is transparent to the public.

The mayor and the NYPD last year proposed replacing Section 50-a with a scheme that would publicize an officer’s name, charges, and the outcome of the discipline process, after completion of the process. Such a scheme, however, would keep the public in the dark as to what were the officer’s actions, what are the rules the officer is alleged to have violated, and what are the possible sanctions to be applied to these violations.

More importantly, the mayor’s proposal doesn’t answer several whys: why a particular sanction was chosen, why similar conduct is sanctioned differently in other instances, why different conduct is punished at a similar level, and why some allegations, after being investigated, are not worthy of any discipline at all.

The Daily News noted several examples two years ago in which the NYPD’s system of discipline seemed to operate “without rhyme or reason,” examples in which officers received different penalties for similar conduct, received the same penalty for wildly disparate conduct, and in which an officer was punished for conduct in which the department seemed to give all others a pass.

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

A strong proposal to replace Section 50-a, however, should result in the release of information that would allow us to answer five questions: who is being disciplined; what is the misconduct alleged and sanction being imposed; why does the misconduct violate the discipline code; when did the misconduct occur; and where is the command in which the officer works. The NYPD currently offers no procedure to answer any of these questions because historically they have been unaccountable to the public and secretive.

Equally as important, a replacement for Section 50-a should release information at the beginning of the disciplinary process, not at the end. By making the process transparent from the beginning, the public is able to understand the values the NYPD seeks to uphold, the conduct which violates these values and the degree to which these values comport with what the people would like to see from their police officers. After all, the system of police discipline is meant to ensure accountability to the people that officers are sworn to serve, not just to arcane regulations in the NYPD patrol guide.

Such a system is not meant solely to answer why, and how, some officers, but not others are disciplined in high profile incidents such as the deaths of Ramarley Graham or Eric Garner. Rather, it would satisfy also the needs of the thousands of persons who every year file complaints with the Civilian Complaint Review Board: more than twenty-five years after a civilian review process was created, persons who have their complaints substantiated by the board still are not told what disciplinary sanction was applied to an officer found to have committed misconduct.

The principle that public servants should be accountable to the people they serve is a simple one. Similarly, the notion that the system of police officer accountability should be transparent to the people they are sworn to serve is commonsensical. The mayor should keep this common-sense notion in mind when developing a replacement for Section 50-a, so as to show he truly cares about making the NYPD transparent.

Christian Covington is an attorney and a master’s student in political science at CUNY Graduate Center

One thought on “Opinion: Fix 50-a, the Right Way”

Unless you eliminate qualified immunity and demand that all police officers obtain personal liability insurance [let the employer pay] you only solve a small part of the problem. Treat them as doctors at a major hospital [professionals?] . When you screw up, you can no longer get reasonable insurance coverage and no one will hire you.