Icons by DOHMH; Graphic by City Limits

I (Ruth) am 65 and I look it. In the past few days, I’ve noticed people darting away from me as I run errands to start social distancing at home: shopping for groceries, refilling my prescriptions, buying books. I saw an anxious mother shoo her toddlers away from “an elderly” as I walked by.

I understand the anxious mother’s reaction. After all, most people know by now that older adults—especially those over age 80—and others with compromised immune systems are more likely to get sicker from COVID-19. People also know that one of the intended effects of social distancing is to prevent transmission of the infection to these high-risk people, both to keep them healthy and to prevent a meltdown of the health system due to mass hospitalizations.

But social distancing, like so many other actions in life, can be helpful or harmful depending on the intentions of those who practice it. Acting out of fear and anxiety, some people adopt a bunker-type mentality, hoarding supplies and sealing themselves off from others. Fear is leading to anti-Asian xenophobia and the stigmatization of older adults and people with chronic illnesses like cancer, HIV, and other immune-suppressing diseases. On the other hand, social distancing with the intent to protect those at greatest risk from getting sick is socially responsible and benefits communities.

So what does socially responsible social distancing look like? It begins with recognizing that social distancing affects people differently. More fortunate New Yorkers can ride out the epidemic in their homes with the support of their spouse, family, and friends, or at least with robust networks accessible through social media. But for more vulnerable people, especially older adults, isolation from friends, relatives, and neighbors can be deadly. Social distancing becomes harmful when it turns into social isolation.

Cutting people off from other people can also deprive them of crucial information. Some of us can go straight to the CDC’s website for trusted information on the ongoing epidemic. But most people get their information through word of mouth. Electronic communications don’t always get through to isolated older adults: New Yorkers age 65 and older are three times as likely as younger residents to be without internet access at home.

But a second reason is more insidious. Numerous studies indicate that the feelings of loneliness that social isolation fosters depression, high blood pressure, and early onset of dementia. A widely cited study estimates that the harmful health effects of chronic loneliness are roughly equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

CDC

Read our coverage of New York City’s Coronavirus crisishttps://citylimits.org/series/the-coronavirus-crisis/For the more than half a million New Yorkers age 60 and older who live alone, the risk of becoming isolated is especially high. The threat is even more dire for the tens of thousands of homebound older adults who are physically unable to leave their homes due to illness or disability.

Older immigrants who are cut off from their communities are also at high risk of becoming isolated. Half of older New Yorkers are immigrants, and of those, two out of every three do not speak English very well. And one third of older immigrants are linguistically isolated, meaning that nobody over the age of 14 in their household speaks English. For this reason, older immigrants are especially dependent on remaining in contact with their communities for access to information and resources.

The good news is that all New Yorkers have the power to protect their older neighbors from the dangers of social isolation. But doing social distancing responsibly will involve making social connections. The easiest way to get started is to pick up the phone and call the older adults in your life to chat and check in on them, especially if you know they live alone. Next, when you pass an older neighbor in the hallways of your apartment building or on the street, ask them how they are doing. Tell them that if they need anything, they can count on you. And then stick to your promise: you could turn out to be someone’s actual lifeline.

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

CityViews are readers’ opinions, not those of City Limits. Add your voice today!

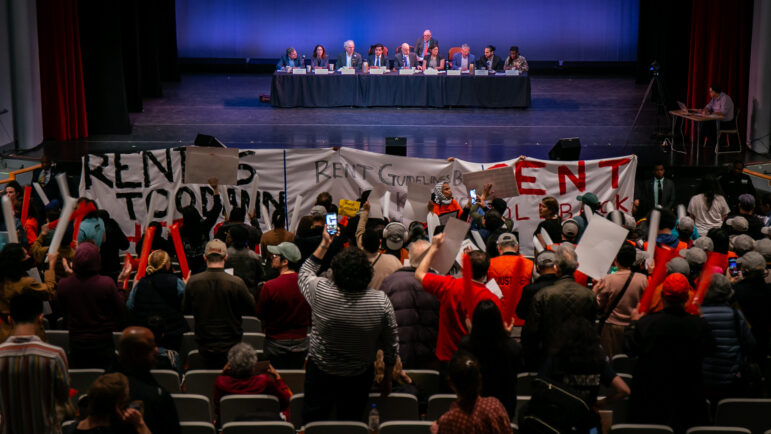

Looking out for older adults is especially important now that the city has shut down its vast network of 287 senior centers. Senior centers provide a crucial lifeline to the more than 30,000 older adults per day from across the five boroughs who depend on them for meals, art or exercise classes, and an opportunity to get out of their apartments and get together with friends. Senior centers are currently scrambling to ensure that their members are not going hungry and to call them once or twice a week to stave off debilitating loneliness.

Senior centers need your help. In addition to the phone calls and offers of assistance that you can extend to the older adults in your life, consider calling your local senior center and asking if they need help making phone calls to their members.

There are several ways to get connected. Council member Brad Lander, is organizing volunteers to make calls to older adults and to help deliver meals and other assistance for Heights and Hills, a nonprofit organization that runs several senior centers in Brooklyn. Up in the Bronx, Neighborhood SHOPP, another nonprofit organization that runs senior centers is organizing volunteers to make calls to the largely lower-income older adults of color that they serve. Surely your local center will have something for you to do, too. Just Google your local senior center or use the New York City Department for the Aging’s directory.

People—of any age—often don’t reach out for help even when they really need it. But by looking out for one another early and often, we can help people avoid getting into crisis. Social distancing should not just be about protecting yourself and your family from the epidemic or avoid passing contagion to others. It should be an opportunity for those of us who have access to social networks, information, and resources to help those who do not. It should be an opportunity to combat ageism and xenophobia by doing something for those that are disadvantaged and marginalized during this crisis. Importantly, it’s something that every New Yorker can do to protect the oldest and most vulnerable members of our communities. We are always stronger together, even if we need to be six feet apart.

Dr. Ruth Finkelstein is the director of the Brookdale Center for Healthy Aging at Hunter College, CUNY . She has a background in public health, grounded at the start of the HIV/AIDS crisis, the last major epidemic changing the future of the world. Christian González-Rivera is the director of strategic policy initiatives at the Brookdale Center.