DOCCS

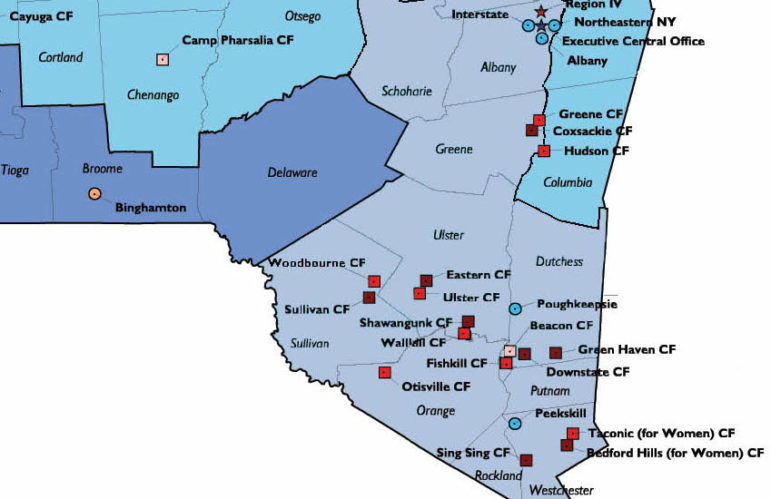

A map of a few of the state’s 45 correctional facilities, which at last count collectively held more people than live in 10 of the state’s 62 counties.

New York has a chance to provide a major win in a growing movement to restore voting rights to people in prison by becoming the third state permitting people to vote from behind bars. Legislation before the state Senate would allow roughly 50,000 incarcerated New Yorkers to vote in the 2020 presidential election if passed in the next legislative session.

The bill would grant people imprisoned in New York the same legitimate, lawful means used to elect representatives in government and hold those officials accountable. Furthermore, it would diminish the need for people in prison to rely on radical measures to draw attention to their living and working conditions, enabling a more safe environment for inmates and prison staff alike.

Without voting rights, prisoners nationwide are waging nonviolent direct action to fight for better conditions.

In 2016, prisoners refused to work for one week, launching the largest prison strike in U.S. history on the anniversary of the Attica Prison uprising. Over 24,000 inmates in 24 states participated, throwing correctional facilities throughout the country into lockdown. The strike was organized around abolishing “prison slavery,” the practice of forcing prisoners to work for little or no pay made possible by the 13th Amendment. (In New York, prisoners make an average of $0.65 an hour, which Governor Cuomo supports increasing.)

U.S. prisoners went on strike again for two weeks in 2018, coordinating hunger strikes, work stoppages, and commissary boycotts. This time they called for 10 reforms, including an end to prison slavery. The essence of the ten demands may be summed up by their first: immediate improvement of prison conditions and policies recognizing the humanity of people in prison.

Quite notably, their tenth and final demand called to restore voting rights for incarcerated people. This was initially considered one of the more radical demands, according to Amani Sawari, an organizer with Jailhouse Lawyers Speak, who acted as a spokesperson for the 2018 prison strike. Yet, as Sawari said in The Atlantic, the prisoners came to see voting rights as the first step to having “political power over getting all the other demands met.”

As it stands, lawmakers have no reason to listen to prisoners or address their concerns. Nor do prisoners have leverage in gaining their interest. As one inmate in a Missouri prison told Vox, “…policymakers have no reason or incentive to get smart on crime. Imprisoned felons can’t vote so they can’t hold them accountable.”

This lack of credibility and accountability explains the prisoners reliance on striking, which is accompanied by often brutal consequences.

In both 2016 and 2018, despite their pleas for human decency, those who organized the strikes from behind bars were retaliated against by correctional staff for engaging in political action. In 2018, they faced “physical abuse, destruction of property, institutional lockdown, and obstruction of access to legal aid, communications, and other resources,” according to Pacific Standard.

Left with no other process for speaking out, these prisoners were forced into making desperate political statements to call attention to their conditions. Yet the retaliation of prison staff only reinforced the violent nature of their environment.

In September, Politico reported on new statistics suggesting a rise in violence on Rikers Island despite major investments to reduce such incidents. This isn’t limited to city jails either. Stories collected in a report from Gothamist conveys “a pattern of unrestrained—and often unpunished—brutality and neglect in the past five years alone, spanning many of the state’s 54 prisons.”

In an interview with Democracy Now!, Sawari explained that “…when a conflict arises or when there’s abrasion or tension in the prison, that easily sparks off into violence, because there is no other outlet for these tensions in high-negative-energy circumstances that prisoners are forced to live within.”

Such tensions sparked into violence in 1971 when prisoners in Western New York rioted and took control of the Attica Correctional Facility, taking 42 staff members hostage. This occurrence, known as the Attica Prison uprising, was based on prisoners’ demands for better living conditions and political rights. Once the uprising was over, at least 43 people had lost their lives, including ten staff members and 33 prisoners.

At the very least, voting rights would establish a baseline outlet for people in prison to advocate on their own behalf and address tensions before they result in full-blown violence. Elected officials and candidates would have motivation to visit these facilities, to meet with prisoners and prison staff, and better understand the issues within these communities.

This could eventually result in legislation addressing their primary concerns, including issues like underpaid prison labor. But left unchanged, we can only expect more strikes, retaliation, and violence to persist in American prisons at significant costs.

Yet right now, New York has a chance to set an example for 47 other states. We have a chance to acknowledge the humanity that prisoners have been denied for over 150 years and the potential to reduce the persistent violence in prison while giving prisoners a means to have their voices heard. However, state legislators are unlikely to act without hearing directly from their constituents.

So if you support voting rights for people in prison, encourage your state senator to co-sponsor Senate Bill S6821, restoring the right to vote to incarcerated people in New York State.

William Fowler is a resident of New York City and an advocate for expanding voting rights. He works for a New York City agency, but the views expressed here are his own.

One thought on “Opinion: Voting Rights Could Improve Conditions, Reduce Violence in NY Prisons”

Excellent analysis on a very important topic