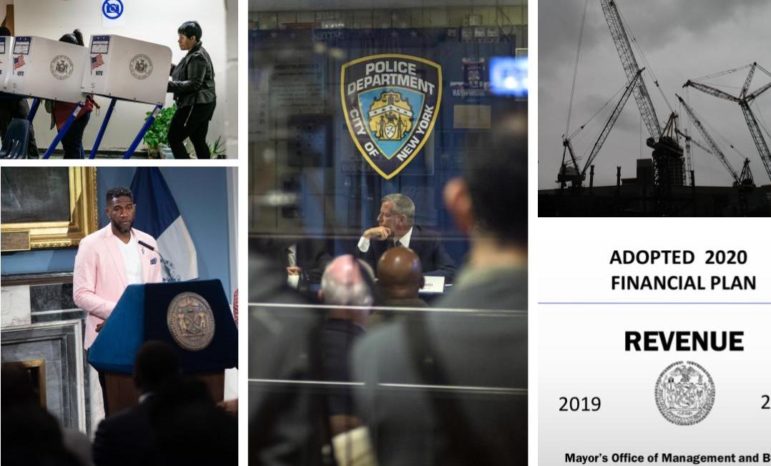

Office of the Mayor, OMB, Adi Talwar

Among the proposed 2019 charter changes are measures altering how elections are conducted, the office of public advocate is funded, alleged police misconduct is investigated, land-use proposals are considered and the city’s budget is composed.

La versión original de esta historia apareció en español aquí.

The original version of this story was in Spanish.

New Yorkers who go to the polls this year will vote “yes or no” on the five questions that the 2019 Charter Revision Commission of the City of New York approved after receiving about 300 proposals from the community.

The commission was composed of 15 members: four members were appointed by the mayor, four by the speaker of the City Council, and one apiece by the public advocate, the comptroller, and each borough president.

These local elections will be a test-run of early voting system that is implemented for the first time in the city. Early voting opened on Saturday, October 26th and closed on Sunday, November 3rd. You can see the English-language guide to early voting here. (The Spanish version is here.) Voting on Election Day, Tuesday, November 5th, begins at 6 a.m. and ends at 9 p.m. Find your polling place here. All registered voters are eligible to participate.

Despite the chance to vote early, members of the charter commission, academics and community activists expect that these elections will see low turnout because they are held in a year when virtually all city, state and federal offices are not on the ballot.

Another factor that is expected to play against voters is the lack of clarity in the proposals. According to people City Limits interviewed, the English version of the measures is somewhat difficult to understand, and the Spanish version is no clearer.

In general terms, five proposals will be voted on and at the end of each proposal will be the question: Shall this proposal be adopted?

Question 1 changes three aspects of how elections are run in New York City.

Voters’ top five: If this question is approved, voters in primaries and special elections for all city offices would be given the option of ranking their top five candidates. The option to vote for a single candidate will remain open. In this ranked-choice voting (RCV) system, if a candidate obtains a majority of first-place votes as the first option, she would be the winner. In case there is not a majority winner among first-place, the candidate who received the least number of first-choice votes would be eliminated and the voters who chose that candidate would have their votes transferred to their selected second-choice candidate. This process would repeat until two candidates remain, and the candidate with the most votes at that point would win the election.

This approach would eliminate post-primary runoffs for citywide offices (as occurred in 2001, 2009 and 2013) and prevent someone from winning a borough presidency or Council seat–for which there is no runoff mechanism–with a minority of votes. It would kick in for elections in 2021.

This question has been the most publicized. Several cities have implemented this voting system for local elections. Research done in those cities shows different results. For example, a New York Times opinion column recently said that when voters can express their preferences in this way, “it’s no surprise that turnout tends to go up.” And RCV advocates say it is less polarizing than the standard two-round vote because candidates must appeal to voters of different backgrounds to win a majority.

However, a 2016 study by Jason McDaniel, a political science professor at San Francisco State University, shows that voter turnout rates declined in RCV systems among Black and Asian portions of the electorate. Additionally, the study found, “RCV increased disparities in turnout between groups who are more likely to vote and those who are less likely to vote. The conclusion is that RCV tends to exacerbate differences between sophisticated voters and those that are less sophisticated.” According to another study by McDaniel, a reduction in polarization cannot be expected with the adoption of RCV. Allowing “voters to rank-order preferences for several candidates does not change the way that voters will develop their first preferences,” says McDaniel.

From the candidate’s perspective, RCV can reward those who build a broad base of support, perhaps by appealing to multiple ethnic groups. RCV does not reward candidates who focus on a single group. At the same time, candidates in RCV systems tend to ask to be the second choice of voters and “this has resulted in several instances of candidates forming ‘cooperative slate’ type arrangements, where they each encourage their respective supporters to rank the other candidate second.”

Extension of vacancy: Right now, there’s a special election within 60 days when there’s a vacancy in the office of mayor and within 45 days when a public advocate, comptroller, borough presidents or Councilmember vacates her or his office. This measure would extend it to 80 days.

Rescheduling redistricting: Every 10 years, City Council district boundaries are redrawn based on Census results and an election is held to elect members from the newly redrawn districts. By current charter, the next round of redistricting–based on the 2020 Census results–would take place from mid-2022 to March 2023. Since the primary for the 2023 Council races would occur in June of 2023, under current law, candidates would begin collecting signatures on nominating petitions to appear on the primary election ballot before redistricting is completed. In other words, candidates would not know the boundaries of the districts for which they are seeking a place on the ballot. This proposed charter change would shorten the redistricting timeline so as to avoid that conflict. It would take effect immediately and its results would be seen during the next redistricting process.

Question 2 affects the operation of the Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB), which investigates allegations of investigates excessive use of force, abuse of authority, discourtesy, or the use of offensive language by police officers.

A bigger board: Right now, the mayor appoints all 13 members of the CCRB, five of whom are nominated by the Council and three by the police commissioner, and the mayor has sole authority to appoint the chair. If adopted, this proposal would expand the CCRB from 13 to 15 members to include a member appointed by the public advocate and one jointly appointed by the mayor and speaker of the Council who would serve as chair. This change also would empower the Council to name its members directly instead of the mayor.

An independent budget: This change would require the city to fund a CCRB staff size equal to 0.65 percent of the budgeted number of uniformed police officers. In this way, if the police department grows, CCRB will grow as well. This reduces the ability of the mayor to manipulate the budget of the CCRB for political purposes. It does not eliminate mayoral discretion, however: The budget requirement would be suspended if the mayor determines that fiscal necessity requires lower spending for the CCRB.

Written explanation from the police: This would require the Police Commissioner to provide a written explanation to the CCRB if the commissioner deviates from the disciplinary measures recommended by the CCRB. If the disciplinary actions to be imposed are less than those recommended, the police commissioner must explain how the decision was made and include each of the factors considered. This explanation must be provided within 45 days of the imposition of disciplinary actions, unless the police commissioner and CCRB board agree to a shorter time.

Cops who lie: Deceitful police testimony is not unheard of: In 2018, the New York Times documented that lies by New York cops helped win convictions in more than 25 cases since 2015. City Limits reported on a different case here. Currently, if the CCRB believes that a police officer made a false statement during the course of one of its own investigations, they can only file a recommendation to the Police Department for further investigation and possible disciplinary action. This proposal will allow the CCRB to investigate the veracity of statements made by an accused police officer during the course of an CCRB investigation. In addition, the CCRB would be allowed to make recommendations on disciplinary action to be taken against a police officer who, as the subject of a CCRB investigation, is not truthful.

Broader subpoena power: This would allow the CCRB board to delegate to its executive director the authority to issue subpoenas to compel the attendance of witnesses, and to seek enforcement of the subpoenas in court.

Question 3 makes changes to lobbying rules and to aspects of the Conflict of Interest Board, Minority and Women-Owned Business Enterprise (M/WBE) program and Corporation Counsel.

Lobbying prohibitionL This proposal would forbid elected city officers and senior officials (deputy mayors and several commissioner-level appointees) from appearing before the agency they served for two years after they finish their service to the city. For this matter, “the Charter defines the term ‘appear’ as any communication for compensation, other than those involving administrative matters,” according to the Charter commission’s final report. The amendment would extend the current one-year term of non-appearance. This wouldn’t kick in until the start of the next mayoral administration in 2022.

Conflict of Interest Board reconfiguration. Currently, the COIB–which is in charge of enforcing and interpreting the ethics laws and rules applicable to public servants–has five board members, all of them appointed by the mayor. With this change the Conflict of Interest Board (COIB) would be reconfigured by replacing two of the current members appointed by the mayor with one member appointed by the comptroller and one member appointed by the public advocate.

Limiting campaign participation: Under this change, COIB members would be prohibited from participating in local officials’ campaigns or donating more than $400 to each mayoral, public advocate and comptroller candidate; $320 to each borough president candidate; and $250 to each City Council candidate.

Cementing M/WBE Office status: Right now, the office that oversees the city’s Minority and Women-Owned Business Enterprise (M/WBE) program is headed by a director who reports to the mayor and a staff based within the mayor’s office. This arrangement is not currently required by law, but this change would make it so.

Corporation Counsel appointment: The Corporation Counsel heads the city’s Law Department, which represents the city (and all its agencies) in civil litigation, juvenile delinquency proceedings and enforcement proceedings in Criminal Court, among other responsibilities. Right now, the “corp counsel” is appointed by the mayor. With this change the Corporation Counsel would be appointed by the mayor with the advice and consent of the City Council.

Question 4 changes the city’s budgeting process.

Revenue-stabilization or “rainy day” fund: This change would be the first step towards the creation of a revenue-stabilization fund or “rainy day” fund in which excess revenues from one year are set aside for use in future years to help fill budget gaps during economic downturns or emergencies. Currently, city law prohibits the use of income received and saved in one year to balance a future year’s budget. If this change is implemented, it would also require changes to state law.

Baseline budgets: This change would set minimum budgets for the public advocate and the presidents of each borough, unless the mayor determines that a smaller budget is a fiscal necessity. The minimum would be based on current-year budgets indexed to the rate of city budget growth or changes in inflation, whatever is smaller. This proposal, which is intended to limit the mayor and Council to manipulate the budgets of other elected officials for political purposes, would come into effect next fiscal year.

Earlier revenue estimate: The annual “non-property tax revenue estimate” is significant because the Charter requires the City Council to set property tax rates sufficient to balance the budget. But the mayor usually submits the estimate at about the time when the budget is adopted in June. The proposed amendment would require the mayor to submit the non-property tax revenue estimate to the City Council when the mayor submits the executive budget in April. The mayor could update this estimate up until May 25th. After that date, the mayor could update the estimate further if the mayor made a written determination of fiscal necessity. This proposed change would take effect immediately so as to allow for this procedure to be implemented for the 2021 fiscal year.

Budget modification timing: This proposed amendment would require that when the mayor submits a financial plan update that contains a change to revenue or spending that would require the mayor to seek a budget modification, the necessary budget modification must be submitted to the City Council within 30 days after the financial plan update. For example, if the mayor wants to update the budget to reflect changes to spending or revenue or to transfer money allocated for one agency or program to another, the mayor must either—depending on the nature of the proposed changes to the budget—seek the approval of the City Council or notify the Council to provide it with an opportunity to disapprove the proposed changes. This would take effect next fiscal year.

Question 5 tweaks the land-use process.

ULURP Pre-Certification notice: This proposed change would require the Department of City Planning (DCP) to send a detailed project summary to the affected community board, borough president and borough board before DCP certifies that a project application is complete and commences the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) public review period. The required summary would have to be transmitted to the affected boards and borough president no later than 30 days before the application is certified, and published by DCP on its website within five days thereafter. Right now, none of those bodies get official word of a project until the seven-month ULURP clock starts ticking.

Additional ULURP summer review time: Many community boards meet less regularly during the summer, complicating their ability to consider ULURP applications that are certified during that period. This amendment would provide additional time for a Community Board to hold a public hearing and issue its recommendation when ULURP applications are certified between June 1 and July 15 of the calendar year. It would give boards 90 days (instead of 60 days) to review ULURP applications that are certified in June and 75 days (instead of 60 days) to review ULURP applications that are certified between July 1 and July 15.

The land-use proposal is the least substantial of the five voters will weigh in on. Several community groups pressed for the commission to give voters the opportunity to approve “comprehensive planning,” but the commission rejected those suggestions in April. According to Gregory Jost, director of organizing at Banana Kelly, the changes proposed do not present “real power for the community.” Kerry McLean at the Women’s Housing and Economic Development Corporation (WHEDco) emphasizes that the “changes are small but necessary, and the more time and the more information the community has, the better.”

Both Banana Kelly and WHEDco say they plan to mobilize their members to vote in November even though the proposed changes are not very significant. On the other hand, organizations such as the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development “do not intend to mobilize their members or their efforts because the Charter Commission did not accept significant changes that we proposed,” ANHD’s Emily Goldstein said.

Questions about the questions? Please contact daniel@citylimits.org.

4 thoughts on “The Proposed New York City Charter Changes Translated into Plain English (Literally)”

McDaniels’ research has been widely disputed. Here’s a more recent paper looking at multiple cities using ranked choice voting, which concludes that “Our evidence is not consistent with concerns about a racial/ethnic bias specific to RCV, but suggests a need for additional voter education.” Other studies show that a good voter education campaign actually reduces ballot errors below current numbers. In other words, voter education is important no matter what.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ssqu.12651

Pingback: Guide to the 2018 New York City Election Ballot: Party in the Back of the Ballot! | Untapped New York

Pingback: NYC’s land use ballot measure, explained | Real Estate Marketplace

Pingback: NYC's land use ballot measure, explained | News for New Yorkers