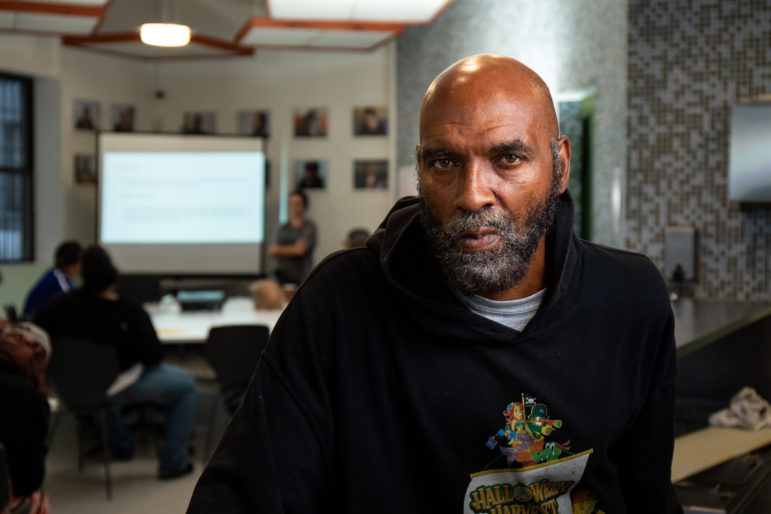

Adi Talwar

Raymond Vaughn has successfully used a CityFHEPS voucher to get an apartment with a roommate. But an eviction looms, and he is worried that the program will not pay enough to let him find a new apartment on his own.

A housing voucher system is one of the main tools the city has to help record numbers of homeless individuals and families move out of shelters and into independent housing. It can also prevent families from becoming homeless in the first place.

While the de Blasio administration’s vouchers have moved tens of thousands of people from shelters into apartments, the program faces challenges. Though voucher discrimination—and lagging efforts to fight that—are significant obstacles, the main issue for a person or family seeking to use the CityFHEPS (Fighting Homelessness & Eviction Prevention Supplement) voucher might be the amount.

At $1,236 for an individual or $1,303 for a two-person household, the city’s voucher for homeless and at-risk individuals struggles to keep up with New York City’s overheating housing market.

Individuals seeking to use the CityFHEPS voucher—and the housing assistants at community organizations throughout the city trying to help them—face a steep challenge.

“The housing stock at that price point is brutal,” says Annie Carforo, campaign manager with Neighbors Together, a Bed-Stuy organization that helps homeless individuals find housing, among many other things.

“We can’t even make calls and get discriminated against,” she says.

There were 59,476 homeless individuals in shelter as of September 9. 16,355 were single adults.

According to the New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey, in 2017, the most recent year for which data is available, there were 16,480 units for rent for less than $1249 per month—roughly one for each homeless adult.

Between 2014 and 2017, apartments available for under $1,249 decreased by more than 14,000 units, a 47 percent drop. It’s likely that since 2017, units available for rent under $1,259 have dropped even further.

If there are 16,355 vacant low-rent apartments out there, they are nearly impossible to find. A search for apartments under $1,250 on the listing site Zillow returned just 100 apartments for rent at or under that amount. On Apartments.com, there were 60. On Street Easy, there were only three.

A very tough market

In addition to searching on traditional listing sites, some vouchers holders and the organizations that assist them turn to Facebook groups or make calls to landlords and brokers that specifically accept vouchers.

“I usually don’t get very many results,” says Miriam Zlotnick, a case manager at an organization that assists homeless individuals.

“There’s nothing really affordable,” says Delores Brantley, a volunteer and board member who assists individuals with housing at the 116th Street Block Association in East Harlem.

That might explain why over 11,000 individuals who hold a CityFHEPS voucher still live in the city’s shelter system, as Gothamist recently reported. As a result, the length of stay in shelter is increasing and the shelter census might too, advocates warn.

“If the city continues to house homeless people at the same rate, the number of homeless will increase,” warns Amy Blumsack, the director of the community action program at Neighbors Together.

Raymond Vaughn is a Neighbors Together member and a formerly homeless individual. He’s had a CityFHEPS voucher over two years now and is living in a room in an apartment in Bed Stuy.

Though the voucher will provide only $1,246 for an individual renting a one-bedroom or studio, it will provide $800 for a single room within another apartment. In some cases, that’s easier to find. The housing specialist at the shelter Vaughn was staying in helped him and another resident each rent rooms in a two-bedroom apartment.

But now, Vaughn says, the landlord wants them out. He’s worried that he’ll have to go looking for another apartment, losing the stable housing he miraculously has.

“I can’t do nothing with it. It’s useless,” he says. “I can’t be choosy. If I had to go to Staten Island or Far Rockaway, I’d go,” says Vaughn.

| CityFHEPS rates vs. HUD Fair Market Rent (Section-8 rates) | ||||||

| Household Size | 1 | 2 | 3 or 4 | 5 or 6 | 7 or 8 | 9 or 10 |

| Maximum Rent with CityFHEPS voucher | $1,246 | $1,303 | $1,557 | $2,010 | $2,257 | $2,600 |

| Apartment Size | Studio | 1-bedroom | 2- bedroom | 3-bedroom | 4-bedroom | |

| HUD Fair Market Rent for New York Metro Area | $1,665 | $1,714 | $1,951 | $2,472 | $2,643 | |

A new system in 2018

In some ways the de Blasio voucher program has been a success following the elimination of the Advantage rental assistance program in 2011, under Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

That program, which provided homeless New Yorkers with rental vouchers for two years, was eliminated when newly-elected Governor Andrew Cuomo pulled state-level funding, which provided roughly half of the program’s budget. It was not a perfect program, but its elimination removed a crucial element of New York’s homeless policy and left the city without a system to help homeless individuals find housing for several years.

A spokesperson for DSS said that the elimination of Advantage was one factor that led to a 38 percent increase in homeless shelter entrants between 2011 and 2014.

When Mayor de Blasio took office in 2014 the city cobbled together a suite of new voucher programs. The system was reformed last summer, consolidating several programs into a program called CityFHEPS (Fighting Homelessness & Eviction Prevention Supplement) with the intention of streamlining the process and aligning the city’s efforts with those at the state level.

The CityFHEPS voucher requires holders to pay 30 percent of their income in rent and the government covers the rest.

To receive a voucher, one must apply through a case worker with the city’s Department of Social Services (DSS). The voucher holder must then find an apartment and submit it for approval by DSS so that the city can perform an inspection. The program will cover the tenant’s security deposit and a 15 percent broker’s fee and pay the landlord four month’s rent up front.

DSS defended the voucher program’s effectiveness, saying that since 2014, over 114,000 individuals have exited shelter with some form of subsidy. Though 11,000 individuals are reported to currently have unused CityFHEPS vouchers, DSS did not provide data about how many individuals have or use vouchers.

“In the midst of an affordability crisis, DSS is using every tool at our disposal to connect our clients experiencing homelessness with opportunities,” a DSS spokesperson wrote in an email. “However, while the city’s overall rental vacancy rate of 3.5 percent poses problems for people of all incomes, renters only able to afford an apartment costing $800 or less must search in a market with a vacancy rate of just 1.15 percent in 2017.”

Legislation contemplated in Albany, City Hall

Lawmakers have known that the voucher amount is too low for a while now. Brooklyn Councilmember Stephen Levin introduced a bill in early 2018 to increase the amount and peg it to the federally-defined fair market rent. The federally administered Section-8 program pays for housing at this rate.

But Councilmembers held off acting on Levin’s bill as they waited to see whether the state would pass Home Stability Support Act, a wide-ranging statewide bill to address and prevent homelessness, which would have raised the amount of the CityFHEPS voucher to 85 percent of fair market rent.

That effort did not pass the state legislature this spring and now some, including Levin, are considering action at the city level to raise the voucher amounts.

“I feel that the voucher limits ought to be increased to fair market rents. If the state is unwilling to do it, then we as a city should do it. I’m open to doing that legislatively, if possible.”

“I’m going to talk about this until I’m blue in the face,” Levin added, suggesting that addressing this issue was his main priority in his last two years on the Council.

City’s efforts to improve

The administration could of course change the amount itself. When DSS consolidated programs last summer, it updated the amount to match level of a parallel state program. The last time the state amount was changed, though, was following a 2017 court case where the state was sued by several individuals who said that the amount was not enough .

There is some concern though, that raising the amount of the voucher will drive up raise rental rates for non-voucher holders at the lower end of the city’s housing market.

“If you just raise the voucher amount, then you risk messing with the real estate market and raising the floor price of rentals,” Catherine Trapani, executive director at Homeless Services United told Politico last year.

The low dollar value of the CityFHEPS voucher is just one problem with the city’s system, however. Discrimination against voucher holders is also widespread.

The city has recently stepped up its anti-discrimination efforts recently, but much more work remains. Critics say the city’s staff dedicated to policing source-of-income discrimination is not nearly large enough for the problem. On top of that, there is some confusion about who should be handling it: DSS has a larger staff and receives more complaints but the city’s Commission on Human Rights (CCHR) can bring cases on behalf of tenants and might be more effective.

The source-of-income unit at DSS has brought three cases against landlords for voucher discrimination since its formation in 2017 despite receiving over 500 complaints. The source of income unit at CCHR brought four in the first half of 2018 after receiving 328 complaints and says that number greatly increased this year.

Property owners say the problem with CityFHEPS is not landlord discrimination but bureaucratic complexity.

“The bureaucracy is above and beyond the levels of bureaucracy that owners would otherwise have to deal with,” says Mitch Posilkin, general counsel for the Rent Stabilization Association, an organization that represents over 25,000 landlords.

The deeper need

Vouchers are popular among advocates because they offer an immediate solution to homeless people’s housing need and tend to keep people out of shelters: According to DSS, only 6.9 percent of individuals and 1.5 percent of families who left shelter to subsidized housing in 2018 returned.

But to advocates and legislators, it is clear that increasing the supply of affordable homes is equally important for a long-term strategy.

A bill by Councilmember Rafael Salamaca hopes to do that, requiring that 15 percent of units in any development subsidized under the city’s Housing New York plan be set aside specifically for homeless people.

“They’re running in concert,” says Levin of Salamaca’s bill. “They’re two important pieces of the puzzle and they speak to each other.”

3 thoughts on “Council Could Try to Force City to Boost Value of Homeless Vouchers”

My wife and I are currently in a couple’s shelter, we have had our CityFHEPS voucher since April 2019… We have been searching for an apartment but the price for a studio or 1bedroom apartments are $1,450 or more and our voucher is for$1,324 so how is anyone able to find or get lucky enough to get an apartment that includes all utilities…. If the program doesn’t give us enough money but pays a shelter nearly $10,000 but can’t raise the voucher so more people can find a place to live….!!!

I absolutely agree the city officials know this and aren’t doing anything the people that own the shelters are making money off of our situation and the mayor isn’t doing anything about it

I have city fheps and im trying to move cause of the heating conditions in my household. However its so hard to find somewhere for me and my two daughters to live. With the amount i get we can only get an efficiency it seems like. I appreciate the help and im very greatful not to be on the streets but this rent is way to high.