John McCarten

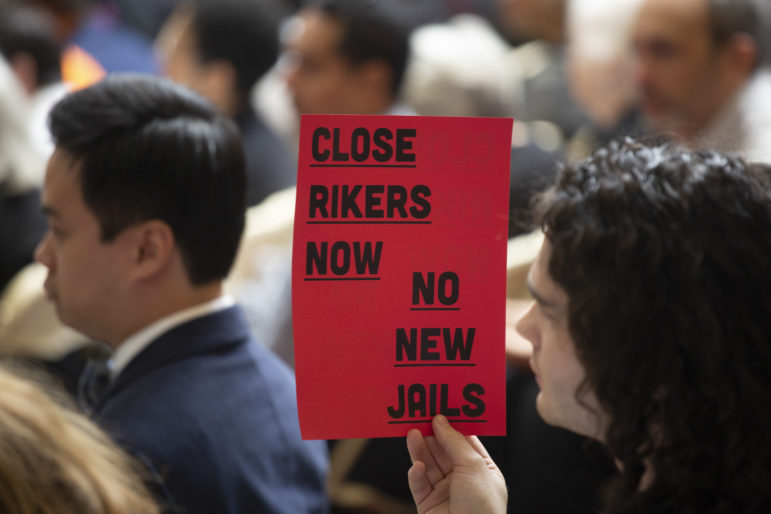

One sentiment at the hearing.

Some 200 people signed up to speak at Thursday’s final public hearing on the plan to create four news jails and close the existing facilities on Rikers Island. That followed hours of testimony by representatives of the de Blasio administration about the plan, which after Tuesday’s approval by the City Planning Commission is headed toward a final series of City Council votes.

The people who sat at the witness table included elected officials, veteran criminal justice advocates, social service providers, at least one retired correction officer, members of the commission that called for closing Rikers, a rabbi and several people who had done time on Rikers or in other city jails.

“Moving quickly to end the torture of Rikers Island is the right thing to do,” Marvin Mayfield told the City Council subcommittee on landmarks, public siting and maritime uses. “The time to close Rikers Island has passed but the best time to do it is now.”

Donna Hilton, who spent 13 brutal months on Rikers as a teenager, wanted to be sure the backstory was understood. “I just want to be very clear that those of us here in this room have led this charge for the beginning,” she said, gesturing to the advocates who help pack the Council Chambers so tightly that people were asked to leave the room as soon as they finished testifying so others could find a seat. “We’ve been fighting for this for years.”

Eloquent voices were raised both in favor and against the plan to build the borough jails, which must now survive a vote by the subcommittee, followed by the full Land Use Committee and then the entire Council. In their testimony and in the questions that Councilmembers directed to the de Blasio administration witnesses, some common themes emerged.

While many of the public witnesses who testified and the overwhelming majority of the Councilmembers said they support the plan for borough jails, many expressed qualms or conditions. And several lawmakers indicated that they would not vote for the plan if those concerns weren’t addressed. Some might have been posturing, but others made clear that they weren’t at “yes” yet.

“My admonition to you is, we need answers and we need them before we vote,” said Coucilmember Barry Grodenchik.

Here are the major concerns that emerged during the first several hours of the hearing. They are unlikely to stop the plan, but at least some of them will be where last-minute negotiations focus:

Number of Beds: The borough jails plan calls for creating enough space for an average daily population of 4,000 people; that’s a revision from the de initial plan, which set capacity at 5,000. Right now, the daily jail census is about 7,000—down from 11,700 at the start of the de Blasio administration, and more than 20,000 in the peak years. Some who oppose the borough jails because they want the city to move away from jails altogether worried that, by definition, the plan would involve adding new beds before any could be removed, and that a future mayor would have to actually decide to shut Rikers down. Some worried that any jail space created would be used – that they’d incentivize the city to find ways to fill it, regardless of public safety needs. The Close Rikers Campaign supports the borough jails but is pushing for a smaller system, of about 3,000 beds.

The Bronx site: As expected, this is the most contentions of the four proposed sites. Unlike the facilities in Brooklyn, Manhattan or Queens, the Bronx site is not where a jail is presently or has been located. It’s on a site that the local community had hoped would be developed in a different way, and it’s more than two miles from the courthouse. Bronx Borough President Ruben Diaz sent a deputy to testify in opposition and the Council’s Land Use Committee chairman, Rafael Salamanca, opened the hearing with a speech deploring the site selection. The member representing the area, Diana Ayala, supports the proposal. The de Blasio administration testified that an alternative site, nearer the courthouse, was too small and would have necessitated a building twice as high.

Height in Queens: Councilmember Karen Koslowitz has supported reactivating the Queens House of Detention site but told administration reps, “The height of this building is absolutely, absolutely, absolutely unacceptable to me. It cannot be that tall.” The mayor’s people said they were”absolutely committed” to working to reduce the planned height.

The Senior Center in Manhattan: Margaret Chin has also supported the plan to build a new facility on or near the current site of “the tombs,” but told the mayor’s reps that she was worried about the relatively small space set aside for community uses and especially on how the new jail, during construction and operation, might affect the clients of the Chung Pak Senior Center, which would share a wall with the jail. The administration committed to having construction liaisons on duty 24-7 at each site, and said it was working to address the potential impacts to the senior center. “Will we get it done before we vote on this?” Chin asked, with a skeptical look.

Current conditions: Many advocates for the borough jails emphasized what is already well known—that conditions in the city jails (on Rikers and elsewhere) are abysmal. But the plan doesn’t envision closing Rikers until 2026. That creates some urgency for addressing the physical and policy reality on Rikers now. City officials insisted the Department of Correction “isn’t the same agency” it was a few years ago. But many advocates were skeptical—some saying they didn’t trust DOC to run the new jails humanely, let alone make Rikers less horrific in the meantime.

Programming: A consistent theme in Councilmembers’ questions was the limits of the land-used review process, which gives the Council power over permits and the use of city property but less latitude to insist on programmatic changes to policing policies, educational offerings in jails, visiting procedures and other facets of life in the current jails and the ones to be built. The administration promised continued efforts to reduce the use of incarceration and make jails more humane, but in the end, the land-use decision can’t guarantee those will happen.

Design and staffing: Koslowitz and others asked about plans for staffing the new jails, in part to understand what kind of traffic and parking impact they might have. But because the facilities have yet to be approved, no designer has been hired. And because no designers have been hired, no detailed designs have been made. And without detailed designs, precise decisions about how much staffing will be needed at each jail have been put off. City officials did say there was no plan for layoffs but that the DOC would shrink by about 100 people per month* through attrition.

Cost: The pricetag for the project remains $8.7 billion, despite a decision several months ago to reduce the height of the facilities and make other tweaks that shrunk the size of the build. The administration says the estimate is the same because it wants room for contingencies, but some lawmakers questioned how realistic the projection is.

Timing: Salamanca and others heaped heavy scorn on the Vernon C. Bain jail barge, which has been anchored off the Bronx for decades even though it was supposed to be temporary is reported to be a particularly horrible place to be incarcerated. The city refused to commit to a timeline for “sinking” the barge because it can’t yet say exactly when construction will start and end at each site, and where the city will move detainees and inmates displaced by the demolition of existing borough facilities. The lack of a timeline frustrated some Councilmembers who spoke at the hearing, although most made it clear that it was not a deal-killer.

Process: More than one speaker faulted the process used to create the plan and move it through public review, saying that community input hadn’t played a meaningful role and that the process had been rushed. Complaints like that dog just about every major land-use application, but the borough jails plan is unique in proposal significant actions at four specific sites through a unified environmental assessment and public review.

Some, however, took issue with the notion that the Close Rikers plan had been rushed, since the idea has been bandied about for decades, was probed by a commission for a year and was formulated by the administration over several months before the official public review began earlier in 2019.

* Correction: The initial version of this article reported that city officials said the DOC was shrinking by 100 employees per year. In fact, they said it was per month.

4 thoughts on “Closing Rikers: The 10 Major Concerns That Emerged at the Public Hearing”

Why hasn’t City Limits investigated or voiced concern over

#1. The Air and Noise pollution and traffic congestion? Building the jails in the locations proposed by the Mayor will be a nightmare for the persons living in the area. The South Bronx has the worst rate of air pollution in the city. Asthma rates are the highest in the nation. Bring correction busses (most of which are diesel) to the area will increase asthma deaths in the area. The main streets in the areas of the jail will probably be closed to traffic as is One Police Plaza. The highways in the area are a major artery to the Triboro Bridge Queens and Manhattan. Increasing traffic will probably increase traffic accidents and pedestrian accidents.

#2. Why does Rikers have to be closed? Why not improve the Jail by over hauling the infrastructure. It would cost a-lot less.

#3. What does the Mayor propose to do with With the property of Rikers Island? Are they going to sell it to a developer? To build more housing for the rich?

No question that the criminal justice system needs major reform and overhaul, including reducing incarceration, reducing bail, good mental health, medical, educational services, decent facilities, training and less stress for guards etc. But still do not see how moving jails from Rikers to borough based jails does any of that?

Why not rebuild on Rikers where there is space to do so? Build a decent facility with a therapeutic environment plus recreation and green space.

Cramming jails into areas with out space or into high rise buildings is absurd and expensive, not to mention logistically and operationally challenging. There will not be sufficient space for what is needed. There will be no green space. Instead of one dedicated expert medical facility there will be four? And thinking about the logistics of staffing, being a guard is not a particularly desirable job. It is tough and stressful. Where are DOC guards (many who cannot afford to live in NYC) going to park? How will DOC manage coverage when guards in one borough are out?

Some inmates may be closer to families but not everyone. Commuting from Staten Island to the Bronx is not easier than to Rikers. Why not just rebuild a good facility on Rikers and set up free shuttle bus and/or ferry service for families and attorneys to Rikers?

If there is “available” space in the boroughs it should be for affordable housing.

The closing of Rikers in one of the most foolish ideas that our City Officials have come up with. The question(s) required should be: Where are the oversight Agencies? (NYC-DOI, NYS Inspector General, U.S. Commission of Civil Rights, etc that have allowed Rikers to become so bad?

Our foolish City Officials have been putting the so called “carriage in front of the horse.”

We should have built the off-site Correctional facilities then empty Rikers. Now, those who do not want the facilities in their neighborhoods are being now forced to accept these facilities, so much for the “rights of the people of NYC.”

Pingback: September 6, 2019 - Weekly News Roundup - New York, Manhattan, and Roosevelt Island | Manhattan Community Board 8