NYPD

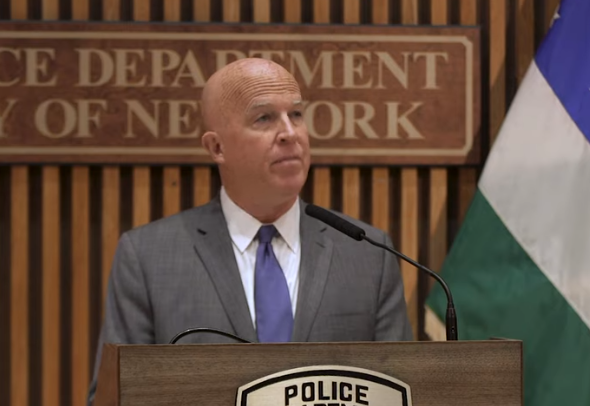

Police Commissioner James O’Neill announces his decision to fire Daniel Pantaleo on August 19.

The NYPD’s decision to fire Officer Daniel Pantaleo over his role in the death of Eric Garner might have—depending on whom you ask—delivered a measure of justice. But there’s little evidence that it has produced closure.

Mayor de Blasio was heckled on live national television about why action has not been taken against other officers who were at the scene of the Garner death. The Police Benevolent Association passed a “no confidence” measure against the mayor and police commissioner. There is no clarity over whether Sgt. Kizzy Adonis, a supervisor at the scene of the 2014 incident, pleaded guilty or not in exchange for avoiding harsher discipline than a loss of vacation days. And officials say there has been a slowdown in arrests since the Pantaleo firing was announced.

Even if the most intense reverberations from Commissioner James O’Neill’s August 19 decision subside, the Garner case will continue to shape conversations about the mayor, the police department and the system in place to oversee cops.

On Wednesday’s WBAI Max & Murphy Show, Civilian Complaint Review Board executive director Jonathan Darche said the Pantaleo decision had taken too long—largely because of requests by local and federal prosecutors to delay the CCRB process in the case—and that the board could need to change how it handles similar cases.

“I think we need to look very hard at whether we respect prosecutorial holds in such a way that they will prohibit us from moving forward in disciplinary matters because of the statute of limitations,” Darche said when asked about the CCRB’s inability to pursue officers involved in the Garner case besides Pantaleo and Adonis who, despite the holds, were served with CCRB complaints within the statute of limitations. “I think [the holds] caused complications and added difficulties in this matter, with regard to Police Officer Pantaleo that we overcame. And I think it makes sense for us to look and see how we will handle these matters in the future,” Darche said.

A former prosecutor, Darche said he believed the slowdown in arrests would be temporary. “I think the professionalism of the members of the NYPD will overcome their anger, and things will proceed.”

But Eugene O’Donnell, a professor at John Jay College who was an NYPD officer before serving as a prosecutor in two boroughs, had a less sanguine prediction. Beyond his concern that many modern cops lack necessary combat skills to overpower opponents without resorting to dangerous moves like chokeholds (“The department itself has to acknowledge that most of these officers don’t have any skills in terms of physically interacting with people,” he says), O’Donnell believes overreach by police reformers like the mayor had hobbled the NYPD’s ability to respond to residents who, despite overall decreases in crime, feel under threat:

It’s an issue of people that continuously complain about issues that don’t have any voice. With 5 million calls a year, the NYPD, and the police acting as their surrogates, de Blasio announced and said that basically the cops are marauders going through communities harassing people, and debunked his own…by stopping that. Police are not doing that on their own volition- they were not in these communities on their own volition. That was being done…to political decisions that were made, and he has curtailed that now. That has consequences, that has collateral consequences that the city has to square with. And the people that are most affected by that don’t get heard. You have an elite who have captured this conversation, and they completely, totally silenced the issue of fear which is palpable and real in at least 3 of the boroughs of the city.

A critic of stop-and-frisk, O’Donnell has also faulted the mayor for blaming cops who were carrying out orders from him, his predecessor and their appointees.

“The New York City police department has a rulebook that is larger than War and Peace. There’s not a single person who can tell you every rule in that rulebook. Many of them are inconsistent, many of them don’t make sense. Cops break the rules every single day, they get the job done, the department knows that,” O’Donnell said. “So if you want to know why there’s boiling outrage, it’s because the department has an absolutely unworkable set of guidelines that are there to protect the department.”

What’s hard to grasp in the wake of the Pantaleo firing is whether police-relations have improved or deteriorated since the Garner’s 2014 killing, and how reliable the CCRB is as a measure of cop-community frictions. Darche says a downward trend in complaints to the CCRB changed direction in 2017, increased in 2018 and is on pace to increase again this year. That could mean more there are more problems, or simply that more people with complaints are finding their way to the CCRB. “We’ve been doing a lot more outreach work we’ve been trying to go where people who are vulnerable and more likely to be victims of police misconduct are, to make sure that they know our agency exists. But also there’s been an increased amount of attention to police misconduct,” Darche says. “And so people may be more aware of the issue. It’s impossible to know what exactly is driving the numbers.”

In November, city voters will decide via referendum whether to increase the strength of the CCRB by approving a five-point revision of the charter’s language governing the board. These include a budget for the board based on the NYPD’s spending level, the addition of two members to the board, and a requirement that the NYPD commissioner explain to the board ahead of time when he plans to deviate from their disciplinary recommendations on particular officers. The CCRB would also be able to investigate and recommend discipline in cases where cops are believed to have lied to their investigators. And it’d allow Darche to issue subpoenas without waiting for board approval. “Which sounds minor,” Darche said. “But most of those subpoenas are for surveillance video in places that often record over video. So the faster we can issue those subpoenas and get video in makes our investigation so much more effective.”

Video, increasingly generated by cameras attached to each cop, is the biggest change shaping police oversight in the city, Darche said.

Body worn camera footage is going to revolutionize civilian oversight all across this country, but especially in New York City. What we’ve seen is, as the body worn cameras have spread across the department, we’re getting more cases that have body worn camera footage. And when we get that footage, because it also has audio in many cases, we are able to make determinations on the merits of our investigations far more frequently than we used to in the past. Right now it’s too soon to give you facts and figures on it, but I think that’s where the future lies for civilian oversight in this city of the NYPD, and we need to make sure that the CCRB has fast and independent access to body worn camera footage.

Here our conversation with Darche or O’Donnell, or the full show, below.

Max & Murphy: Full Show of August 28, 2019

Max & Murphy: CCRB Chief Discusses His Agency’s Role in the Eric Garner Case

Max & Murphy: Eugene O’Donnell Sees City Hall Failures in the Garner Case

With reporting by Cyan Hunte

One thought on “What the Pantaleo Decision Tells Us About Police Accountability in New York City”

I was a CCRB investigator more than a decade ago.

CCRB complaint data has often been used to make claims about police restraint, and police-community relations based on volume of complaints of the four different types under its purview. But the mere measure of complaints by categorical type offers no way of accounting for the reasons behind fluctuations in the volume of complaints.

A declining rate of CCRB complaints can be as easily explained by rising fear over making complaints as it can be explained by a decline in the police use of excessive force or abuses of authority. And it might mean both simultaneously, for different populations and in different city nodes.

The lesson I took away from my time at CCRB is this: Yes there are some bad apples in the NYPD. And there are some good ones. But the oversight the public really needs over its police department can’t just be about holding individuals accountable, because it leaves structural issues untouched.

The CCRB needs oversight to confront NYPD structural issues that are generative of contexts likely to result in misconduct, and mistrust in police. We the people should be able to have a say in how we are policed, and to make interventions into an institution with overwhelming power to shape quality and nature of urban life.