Murphy

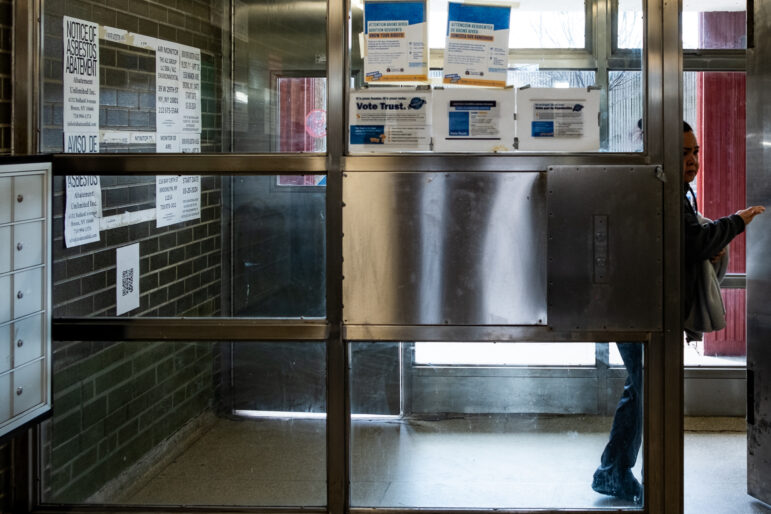

The Washington Irving Branch of the Brooklyn Public Library, one of the cooling centers in Bushwick.

New York City health officials have not pinpointed heat as the primary cause of very many deaths in recent years. On average, about 13 deaths are chalked up to heat stroke annually. That’s 13 people too many, of course, but far less than die from, say, accidental falls, which claimed 500 lives in the city in 2017.

Heat’s potential to kill in large numbers, however, is undeniable. As the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene wrote in a study of heat-related deaths in 2013, “Extreme heat events kill more people, on average, than any other type of extreme weather event in both New York City and the United States overall.” The 1995 Chicago heat wave killed 700 people over five days.

Dying of heat stroke is not the only way to lose one’s life because of heat. “Heat-related” deaths represent a larger number of individual cases in which heat is a factor in, though not the sole cause of, a fatality. DOHMH says there are about 115 of those each year. DOHMH research indicates that heat-related deaths in the city are strongly associated with extreme heat events, rather than everyday warm temperatures. Seventy-three percent of heat-related deaths in the city in 2013 were associated with a one-week heat wave.

(Another measure, “excess deaths” from heat, is estimated statistically to reflect higher numbers of deaths associated with some heat event. According to some research, the 2003 European heat wave factored into more than 30,000 “excess deaths,” more than 14,000 of them in France alone.)

Given the likelihood of warmer summers and the possibility of more, longer and hotter heat waves as climate change progresses, there’s growing attention to the problem of extreme heat in New York City—although it often gets overshadowed by other risks associated with global warming, like rising sea levels and more intense coastal storms.

Get the best of City Limits news in your inbox.

Select any of our free weekly newsletters and stay informed on the latest policy-focused, independent news.

Scientists generally say it’s a stretch to attribute individual weather events to climate change. But the heat wave predicted for this weekend could be a harbinger of what New York will face more frequently in the summers. It will also be a test of the city’s policy response to heat. The mayor has activated hundreds of cooling centers and signed an emergency order commanding office buildings to reduce air-conditioner use to avoid power outages.

Data from 2013 indicates that some New Yorkers are more vulnerable to the heath risks of heat that others. People aged 65 or older made up a third of the 26 heat-related deaths that year. Almost everyone who died suffered from some other risks factor, like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, serious mental illness or cognitive impairment, or drug use.

These factors show up in other heat emergencies: In a case study of the 1995 Chicago heat disaster, AdaptNY finds that older people died at higher rates than their counterparts. But race and poverty were risk factors, too. Referring to a report by the Illinois climatologist, AdaptNY said factors that aggravated that heat wave were an inadequate local heat wave warning system, power failures and inadequate ambulance service and hospital facilities. Uneven access to air-conditioning was a major issue.

New York City has certainly warned people in advance of this week’s heat wave. But the recent power outages on the West Side and Staten Island raise concerns about how the grid will hold up on Saturday. At last count in 2014, roughly 87 percent of households in the city had central air-conditioning or at least one window AC unit. But those systems don’t do much when the power is out.

Heat can be more intense in some neighborhoods because of their built environment – less tree cover, more blacktop – or geography (places located on higher ground get breezes that lower-lying neighborhoods do not). Bushwick, where City Limits is pursuing a special reporting project, feels like a hot place, although one expert we contacted said it is not among the very hottest in the city. There is little tree cover, however. The two libraries in community district 4, the Brooklyn Public Library’s DeKalb and Washington Irving branches, which also serve as cooling centers, were full up with people seeking air-conditioning last week, well before the heat wave arrived.

Councilmember Rafael Espinal, who represents most of the neighborhood, says his green roof bill—which the Council passed this spring—will help to change that. “If every new development in Bushwick had a green roof and there are retroactive roofs that are installed—sustainable roofs—we’d see the heat island effect decrease,” he said. “I think over time, our city as a whole is going to cool off, but especially in communities that are just all asphalt and concrete, we’re going to have a greater impact.”