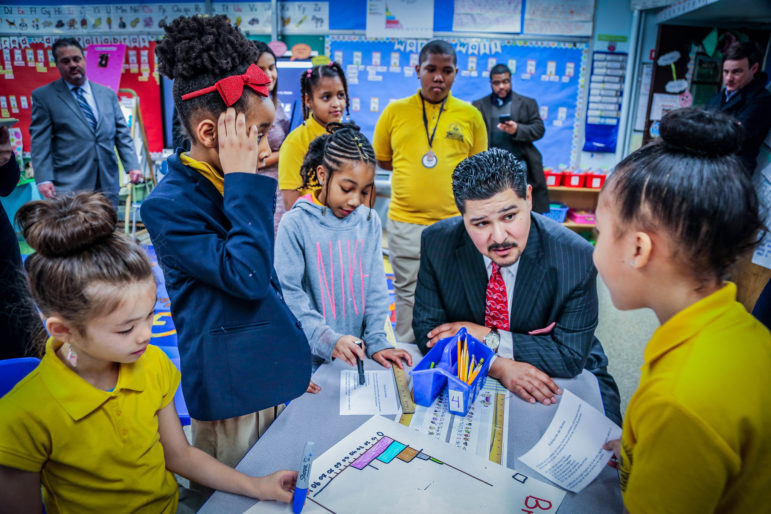

NYC DOE

Chancellor Richard Carranza has identified segregation as a major obstacle to improving New York City Schools.

The segregation of New York City schools is complex, with the system’s four broad racial groups present in at least 12 discernible patterns of singular majority or shared dominance, all of it linked only loosely to the city’s underlying housing segregation, a report released Tuesday concludes.

The Furman Center report examined the racial and ethnic diversity of the city’s public elementary schools and their neighborhoods. The overall analysis found that most public elementary schools have one ethnic or racial group that has a significantly larger presence compared to other racial or ethnic groups and that while “the concentration of racial and ethnic groups has grown less extreme over the past 12 years for Black, Hispanic, and white students,” data shows students from Black, Latino and lower-income backgrounds remain isolated when compared with their Asian or white peers from higher-income backgrounds.

The report noted that, system-wide, the schools’ demography is evolving. Between the 2005-2006 and 2017-2018 school years the city saw declines in the share of students that were Black and in increase in the share of Latino students in public elementary and charter schools.

In the 2005-06 school year, an estimated 64.9 percent of charter elementary school students and an estimated 32.3 percent of traditional public elementary school students were Black. By 2017-18 school year, the share of charter elementary students who were Black dropped 11.9 percentage points to 53.0 percent and in traditional public elementary schools the Black student population dropped 6.8 percentage points to 25.5 percent. However in both cases, the drop in Black students was supplemented by an increase in Latino students by an estimated eight percent. The report said the trend reflected a larger pattern of change the city’s population demographics.

The report found Asian and white students are more segregated in traditional public elementary schools than Asian and white residents are in neighborhoods. The average Asian traditional public elementary school student attended a school that was an estimated 43.7 percent Asian. Latinos students were also more likely to see same-group peers in their schools than in their neighborhoods but the difference was minor.

Get the best of City Limits news in your inbox.

Select any of our free weekly newsletters and stay informed on the latest policy-focused, independent news.

However Black and White students, “had fewer same-group peers in their schools than in their neighborhoods.” The report continued: “On average, white and Black New Yorkers lived in school districts that were majority white and Black respectively, while the traditional public elementary schools they attended were not.”

The most powerful conclusion from the report is that school segregation and housing segregation are not exactly two sides of the same coin, as some would argue.

“We find that while neighborhood composition shapes school diversity, racially/ethnically diverse neighborhoods did not necessarily house traditional public elementary schools that reflected the same diversity, and when a neighborhood diversified over time, the change in the related school population was often modest,” the authors wrote. “In other words, diversifying the city’s neighborhoods may be a necessary step to diversifying its schools, but it is not sufficient.”

The report can be read here.

One thought on “Racial Skews in City Schools Not Solely Linked to Housing Segregation, Says Report”

The NYC school system is only about 15% white so there aren’t enough white students to spread around to integrate the system.

https://infohub.nyced.org/reports-and-policies/citywide-information-and-data/information-and-data-overview#jump-to-heading-25