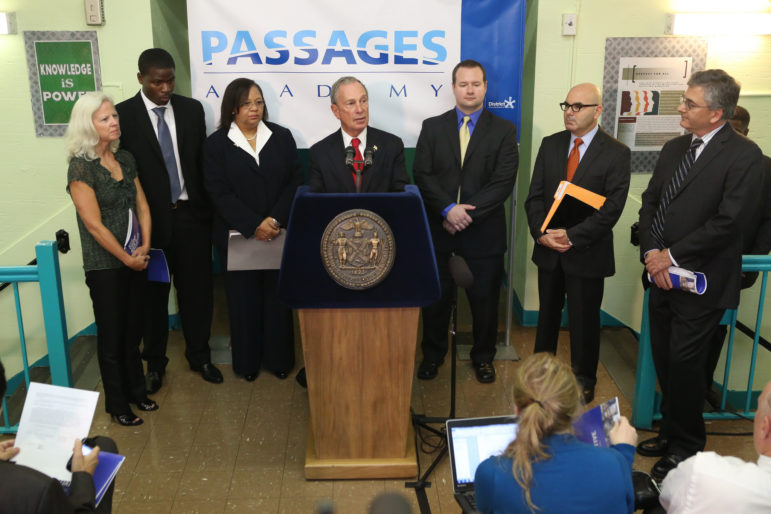

Spencer T Tucker/City Hall

Mayor Bloomberg (joined by Deputy Mayor Linda Gibbs at far left, ACS commissioner Ronald Richter, second from right, and Probation Commissioner Vincent Schiraldi) marks start of ‘Close to Home’ Juvenile Justice Program on October 4, 2012.

Most times, the progress we see on issues of public concern is the effect of a policy change. Like the 1990s “Safe City, Safe Streets” initiative and Compstat system put New York City on the path to transformative reduction in crime. Or Title IV of the Clean Air Act, which basically eliminated the problem of acid rain that had once seemed insoluble. Or Mayor Bloomberg’s smoking ban, which made the once inescapable smoky bar seem like an artifact from some New York of long ago, and lengthened lives, likely tens of thousands of them.

Sometimes, however, the policy change itself is the success. The Close to Home legislation pushed by Bloomberg and signed into law by Gov. Cuomo in 2012, which gave the city control of children whom courts labeled “juvenile delinquents,” is one example. The law helped shift a system that in the mid-1990s sent 3,800 city kids to state detention facilities mostly located outside the five boroughs to one where, as of this month, not a single city child who went through Family Court was in custody outside the city, and only 107 kids were in residential facilities within the city—only 12 of them in locked residences. (Another 51 youths tried by criminal court instead of family court, most of them as adults, were in secure state facilities.)

A report out Wednesday from the Columbia University Justice Lab ties the Close to Home (a.k.a. C2H) program to many measures of achievement. Ninety-one percent of Close to Home youth passed their classes in the 2016-2017 school year. The number of kids who left their resident without permission plummeted. And when it comes to crime:

To date, there are no longitudinal data showing recidivism rates of youth in C2H. However, initial measures suggest that the initiative has not jeopardized public safety. Since C2H began, juvenile arrest rates have declined at an accelerated rate. In the four years preceding C2H (2008- 2012), juvenile arrests in New York City declined by 24 percent, while in the four years since C2H implementation began (2012-2016), they declined by 52 percent. Moreover, between 2012 and 2016, youth arrests in New York City decreased by 28.5 percent more than in the rest of the state during this same period (52 percent versus 41 percent), which did not pursue C2H.

Some of that success can be chalked up to a well-implemented program. But a lot of it, like the Close to Home program itself, is the product of a long and multifaceted transformation in how the city thought about crime and young people.

After a huge increase in the number of New York City youth in detention from the 1970s to the 1990s, attitudes began to change—nudged, in part, by a steady fall in juvenile crime. Voices calling for reform grew louder as the century turned, with members of Bloomberg’s administration launching initiatives to reduce youth detention as early as 2003. The 2006 death of 15-year-old Darryl Thompson after being restrained at a state residential facility hastened the push for reform, and a federal investigation launched the following year gave proponents crucial leverage. The presence of reformers in key positions—Gladys Carrión at the state Office of Children and Family Services, Martin Horn and then Vincent Shiraldi at the city Department of Probation—was key, as were elected officials (especially Bloomberg, Cuomo and to a lesser extent Govs. Eliot Spitzer and David Paterson).

Meanwhile, advocates like Legal Aid, Human Rights Watch, the Correctional Association and Children’s Defense Fund played a critical role in surfacing evidence of the system’s problems and getting the voices of youth and family members heard.

The momentum created by these efforts made Close to Home, which would have seemed a radical move a few years earlier, appear to be a significant but logical step. Both politically and in terms of the capacity of the agencies charged with carrying out the change, the groundwork had been laid, the report says.

Not that implementing Close to Home was simple. Among other ingredients, that required intensive staff training, skilled nonprofit partners and, the Justice Lab report argues somewhat controversially, the ability to bypass the city’s land-use procedure when siting resident facilities, an end run around anticipated NIMBY opposition.

Despite the dramatic change it embodied, Close to Home still faces challenges. Ironically, some are the creation of its architects, like Cuomo’s slashing of Close to Home’s budget last year, leaving a tab that Mayor de Blasio picked up. Other pressures are the result of subsequent waves of reform, like the Raise the Age legislation that shifts many cases involving 16- and 17-year-olds out of criminal court into Family Court.

And then there are the problems that stem from the fact that Close to Home has to interact with other, troubled systems. For instance, “While youth make educational progress while in C2H educational programs, preliminary information suggests that these gains dissipate once youth return to their home schools,” the report says. “While in C2H, youth get tremendous support from teachers and other adults, often in small classroom settings. Sadly, this type of support is not typical for a mainstream school and so young people disengage. Finding ways to address this issue will require resources beyond the juvenile justice system.”