Alex Proimos

The revenue collected by the two ticket-abatement programs is still just about 10 percent of what the city hauls in each year from parking violations overall.

Delivery companies like UPS, FedEx and FreshDirect shelled out more than $51 million last year for committing parking violations on city streets—but the biggest offenders still collectively saved as much as $10 million in fees thanks to a controversial city abatement program, a new report says.

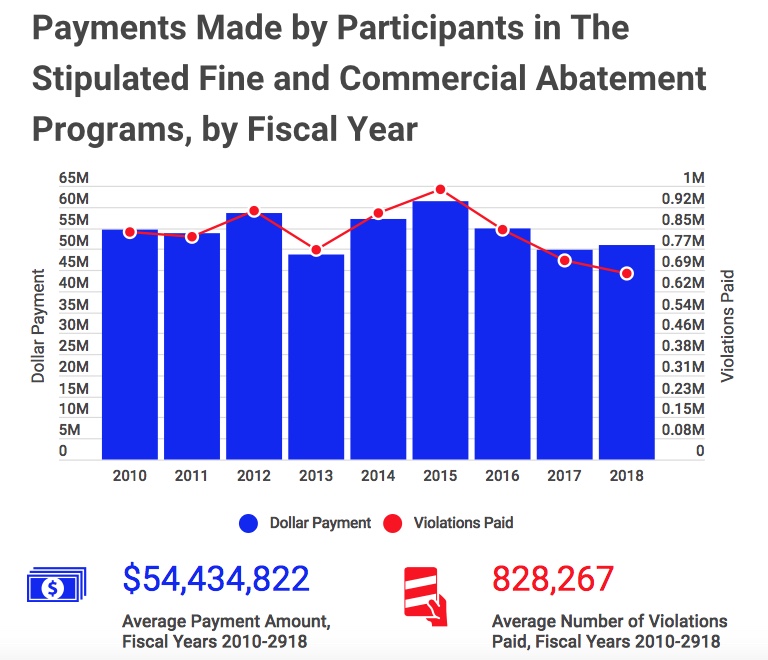

The Independent Budget Office (IBO) released a report Tuesday looking at how much money the city collected over the last eight years through two initiatives designed to help delivery companies deal with parking ticket fees: the Stipulated Fine Program and Commercial Abatement Program. Both allow participants to qualify for reduced fines for certain parking offenses, as long as the companies agree ahead of time not to challenge the tickets they receive—an effort to free up space and resources in the city’s traffic court system.

Since 2010, the city has collected an average of $54 million each year from both programs, with most funds coming through the Stipulated Fine Program, which is for larger companies that have more drivers on the streets, according to the IBO. Last year alone, participants in the two programs paid out $54,434,822 for 828,267 parking violations, the report says.

The report shows which big-name companies that participate in the Stipulated Fine Program racked up the most offenses last year: UPS took the top slot, paying more than $14 million in fines for 164,580 summonses in 2018. Federal Express, Verizon, Manhattan Beer Distributors, FreshDirect and Time Warner Cable also ranked among the 10 most heavily-fined companies, according to the report.

Those businesses could have owed much more without the abatement initiative: The report estimates that those top 10 participants collectively saved up to $10 million in 2018 thanks to the Stipulated Fine Program, though IBO points out that that doesn’t necessarily translate to lost city revenue.

“Because the summonses are not contested in traffic court and some of the violations likely would have been dismissed or reduced had they been, it is impossible to determine the amount of revenue the city would have collected without the program in place,” the report says.

Both abatement programs have been criticized in the past by transit advocates, who see it as a giveaway to delivery drivers that encourages bad curbside behavior. Commercial drivers, however, argue the reduced fines help keep businesses moving in a city where parking spots and loading areas are becoming increasingly harder to find.

In December, the city’s Department of Finance increased many of the violation fees in both programs. Under the current fine structure, participants receive no discounts at all for certain offenses, including idling and bus lane violations. But they still pay less for others: Parking in a street cleaning zone below Manhattan’s 96th Street, for instance, would normally land a driver with a $65 summons, but is reduced to $25 under the abatement programs. Blocking a driveway, usually a $95 penalty, is cut down to $60.

Even with the higher fees, some critics would like to see the initiatives kicked to the curb altogether. In October, a group of City Council members introduced a package of bills to address street safety issues related to commercial deliveries, including one that would abolish the Stipulated Fine Program.

“Massive delivery companies shouldn’t get a free pass — which many times they literally do — for illegally parking in front of fire hydrants, blocking bike lanes, or eating up handicapped spots,” Councilmember Costa Constantinides, one of the bill’s sponsors, said at the time.

In a statement, the Department of Finance said the companies enrolled in the abatement programs are now paying 27 percent more thanks to the fine increases that were implemented in December. It also disputed the IBO report’s characterization of the programs as offering “reduced” fees, but instead pay a price that’s in line with what they’d be fined if they challenged their tickets in court.

“Participants waive their right to a hearing where they could present commercial defenses from New York City’s parking rules for expeditious deliveries. In exchange, they pay the expected outcome if a hearing were to be held,” the agency said in a statement.

The revenue collected by the two ticket-abatement programs is still just about 10 percent of what the city hauls in each year from parking violations overall, the IBO report says: Parking ticket fees net about $532 million annually, according to the report.

You can read the whole thing here.

Get the best of City Limits news in your inbox.

Select any of our free weekly newsletters and stay informed on the latest policy-focused, independent news.

4 thoughts on “Report: City Discounts Saved Delivery Drivers Up to $10M Last Year”

“Massive delivery companies shouldn’t get a free pass — which many times they literally do — for illegally parking in front of fire hydrants, blocking bike lanes, or eating up handicapped spots,” Councilmember Costa Constantinides, one of the bill’s sponsors, said at the time.

Actually, it’s car owners who are getting a free pass. Car owners store private property on public streets for free. They call it “parking”. They obstruct delivery companies and commercial vehicle operators from going about their business. Free or underpriced on-street parking for private cars should always cost more than nearby commercial parking. And on-street loading zones for commercial vehicles should be prioritized over on-street parking for cars.

Deliveries have to made on time. Delivery trucks can’t always park in the loading zones. The city program makes sense.

Pingback: The Race to Be Exempt from New York's Congestion Pricing Is On * Carinsurance

Pingback: Surprise: Tons of New York Drivers Are Trying to Get Out of Congestion Pricing - Jalopnik - All About Finance