Office of the Mayor, Adi Talwar, Eileen Markey

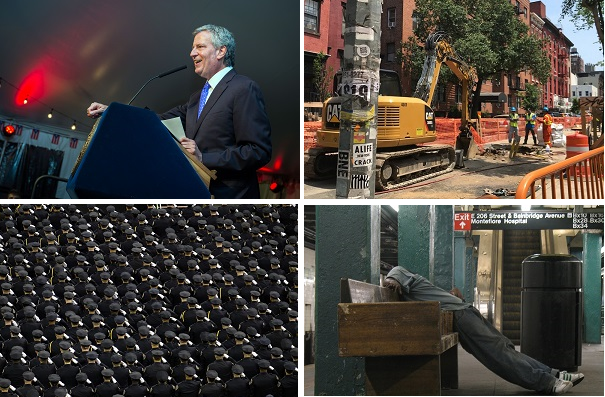

The powers of the mayor, the process for deciding how land is used, the responsibility for homeless services and oversight of the police are among the areas where the Charter lays down the law.

As governing documents go, the New York City charter is pretty prosaic. No painstakingly preserved copy of the original exists in a hermetically sealed case. There have been no musicals about it, and it is unlikely there will ever be a museum dedicated to it. It lacks the pioneering aura of the Flushing Remonstrance or the legendary backstory of the Connecticut Royal Charter (which settlers supposedly hid in a tree to keep the English from taking it back).

All the charter is is very important to the everyday operation of the largest city in the United States—to the separation of power, checks and balances, the governing of land, the transparency of city services.

Three proposals to change the charter are on the ballot for this November, products of a mayoral commission that met earlier this year. A more fundamental set of changes is likely to be considered by a second commission launched by the City Council and meeting over the next several months.

That presents an opportunity to change how power is apportioned and authority wielded in the city. And so Generation Citizen, a nonprofit that engages young people around the country in project-based learning involving real-life civic engagement, is hoping to equip New York’s eighth through 12th graders to take a hand at shaping that change.

GC has released a curriculum for school teachers to use to bring students up to date on the charter and help them select elements they want to change, scrap or add, and then work to make that happen. It’s a two-lesson plan (GC also offers a semester long Action Civics course) that emphasizes that “All action is purposeful and valuable.”

City Limits spoke with DeNora Getachew, the New York City Executive Director for Generation Citizen (GC) and Martin Mintz, the organization’s New York City program manager about the effort. The lesson plans (which would be helpful to non-teachers and non-students for their clear explanation of how the charter works and what’s at stake in the revision process) follow:

CL: If you were approached by an eighth or 12th grader who asked, why does the city Charter matter, what would you say?

Mintz: It’s a really great question because I think the charter itself is something that a lot of people—students and adults—might not even know exists. But I’ll answer that question by saying that it affects how our city runs no matter who you are living in our city, whether you are zero or 100. And the charter revision itself is your chance to have a say in our how the charter is written, how it affects your community.

Getachew: It goes to the heart of our mission here at GC, which is why we focus on local politics. We care about how our city is governed and want to make sure it’s responsive to our needs, and we want our charter to reflect that. It’s a chance to weigh in on that at the most local level.

CL: How much of this is about teaching kids about the charter issue and how much of it is kind of a primer on city government writ large?

Mintz: The first part of the lesson plan really does teach students about the history of the charter and specifically the city’s two charter revision commissions. So a good part of it is about understanding, A, how does a charter affect my city and my life?, but also, how is it actually working in a local government? … We have the mayor’s three issues up for a vote in November and then the second revision commission that our students would actually be—through the lesson plans—taking action to share their ideas. … Once they develop an understanding of what’s inside the charter, that next step is the action part. We want kids to be interacting with this charter but creating an action step afterwards: that first step would be identifying a topic, a specific thing they would like to amend or revise and then sharing that with those who are listening to them, making sure their voices are a that table as well.

Getachew: What is very powerful about this moment and what was the impetus for us in creating the lesson is there’s this incredible momentum in favor of youth led change and abysmal turnout, if you will, at the local level in our elections. In the 2017 elections, 23 percent of New Yorkers turned out to vote to elect their mayoral and city council, et cetera. When you look under the hood of that, it’s about 11 percent of eligible youth. And yet those same young people sit in GC classes and want to make their voices heard and don’t always feel like they have the tools to do so. So we always talk about, what is in in your advocacy tool kit? What are the tools you can use to make change? If young people actually want to make change, we want to make sure there are tools in their tool box that can do that. The charter revision – the fact that there are two of them happening in overlapping or consecutive fashion – is just another way to give them a tool to effect change locally.

CL: Do you feel like this is building on a foundation of civics education that already exists?

Getachew: The reality is, we have the underpinnings. The State Education Department gives frameworks to teachers statewide. There are frameworks that exist for teaching civics in the classroom, particularly in this “Participation in Government” mandated class. But so much of it is not about giving students, or teachers, the ability to engage in project-based learning. It’s rote memorization of random government facts, again. … That’s not what we’re doing in a 21st century democracy when young people can like it, hug it and retweet it on the Internet and think that that’s how they effect systemic change. There is incredible momentum in favor of moving toward action-oriented civics education in the classroom. … But we’re not there yet. The power of these lessons is that it’s action-oriented, can be student led … and its contemporaneous. It’s giving teachers a tool to talk about what’s happening right now in their city and connect it to something that’s real and tangible—not the theory of civics, that someday there might be a commission. Right now, there are two commissions and one is on the ballot.

CL: Do you expect some of this to kind of filter through to the kind of broader community, to the adults that live with and interact with these students?

Getachew: That’s always a goal with the work that we’re doing. The primary beneficiaries of our programs are the students in the classroom. Our hope is that they will go home and spark these civic conversations around the dinner table. [Those conversation partners] are a secondary beneficiary of the work. But the target audience is really about getting this current generation to understand and, as we say, not just talk about change but actually lead it.

CL: How do you teach the students to deal with the disappointment of losing, or pushing an idea that doesn’t take off – a big part of life in the civic realm?

Mintz: I think that’s something that’s super important to kind of front load as a teacher. You’ll see it in our general Action Civic course. There’s a civic disposition, and the fact that even though you might be working on something for, whether it be two lessons or for a whole semester, change doesn’t happen like the flick of a switch. That’s something that might be difficult to learn but it’s extremely important to learn. As we talk about students being civically engaged, yes, the first, second, third step might not look like you’re getting anywhere, but that’s part of the journey.

Getachew: I think that context is often lost on young people. The fact that we have so much technology at our disposal at all times has lulled us into a false sense of security that everything will be instant, right? That everything will happen immediately. I will say (and I say this to young people all the time), yes, technology has fueled and accelerated the pace at which change happens. But change, like the systemic change that were advocating for in our classes and we want the charter commission to implement, that kind of change takes time. The classic example is, from the convention at Seneca Falls to when the 19th Amendment happened was 72 years. I mean yeah, maybe Twitter would have fueled that a little bit quicker but at the same time it also creates a lot of noise about what are the priorities. I recently gave a talk to educators about how do we make sure that we’re empowering civically engaged digital learners that understand how to use the tools in their toolbox but also understand the arc of history and how long it takes to accomplish systemic change.

2 thoughts on “A Lesson Plan for Remaking New York City Government”

Pingback: Generation Citizen New York City Endorses Charter Revision Commission Ballot Proposals | Generation Citizen

Pingback: Flip Your Ballot: GC Endorses All Three NYC Ballot Proposals | Generation Citizen