Adi Talwar

Dister says he has frequently been approached by police officers in situations where he did not feel free to leave. But those encounters likely did not show up in the official tally of 'stops.'

One fall evening about two years ago, a man named Dister was walking with a friend in Washington Heights, near 173rd Street, when he was abruptly approached by a pair of police officers.

“Hey, where you guys going? Are you coming from a train station?” Dister recalls them asking loudly.

Dister, who does not want his last name published, saw no apparent reason for the officers to approach him and his friend in the first place.

He perceived the officers’ questions as unnecessary and confrontational, but said he didn’t feel comfortable ignoring them or just walking away. These kinds of experiences have been a regular occurrence for him in his Washington Heights neighborhood, he said.

For Dister, the era of “stop, question and frisk” isn’t over. Experts warn that he isn’t alone in his experience, although it is hard to say how common it is because similar episodes affecting numerous New Yorkers may never show up in the NYPD’s statistics.

Official stop numbers have plummeted since a groundbreaking federal lawsuit in 2013 ruled the NYPD’s stop and frisk tactics unconstitutional. But those statistics only reflect the most serious type of stop. Other encounters which don’t meet the standard of a high-level stop take place without leaving a trace in the public record.

While the NYPD calls such stops “low-level,” advocates say they can still leave residents feeling intimidated and targeted, such as when the officer approached Dister and his friend.

“[Stop-and-frisk] numbers don’t accurately reflect anything of the lived experience of people of color in their communities,” said Darian Agostini, a youth organizer for the non-profit Make the Road New York.

In an attempt to address the disconnect between data and reality, members of the original lawsuit filed a recommendation with the courts on Friday, June 8. They ask that the court require the NYPD to keep a record of lower-level stops, not just those deemed most severe.

“The only way to ensure and monitor whether officers are lawfully exercising their authority is to have some record of those [low-level] encounters,” said Jenn Rolnick Borchetta, director of impact litigation at The Bronx Defenders and an attorney in the stop-and-frisk case.

“To me, the supposedly enormous decrease in stops is an NYPD bait-and-switch in plain sight,” she said.

What the numbers don’t reveal

The reporting of low-level encounters is one of the latest concerns in an ongoing debate over stop-and-frisk. Reforms have taken place since the landmark lawsuit in 2013, when a federal court ruled the way the NYPD had been carrying out stops was racially discriminatory and therefore, unconstitutional; it ordered the department to reform the practice.

Yet despite five years of ongoing reforms, concerns linger.

While the number of stops has plunged from a peak of nearly 700,000 stops in 2011 to just under 11,000 by the end of 2017, stops still overwhelmingly target people of color, according to an official analysis of stops from 2013-2015. The NYPD has claimed that its stops are based on descriptions of suspects from witnesses and victims over 311 and 911 calls, and that the decrease in stops demonstrates a more targeted approach to policing.

Some remained unconvinced by this explanation. “Racial disparities are essentially unchanged” from before the court’s ruling, said Darius Charney, senior staff attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights and one of the attorneys on the stop-and-frisk case.

“[The NYPD] is still targeting stop and frisk at primarily young people of color and they’re doing it, we think, very intentionally. And that’s not only a problem; that’s illegal,” he said.

But in addition to the official disparities, “low level” police interactions in historically overpoliced neighborhoods can escape scrutiny altogether, since they don’t have to be reported.

The levels

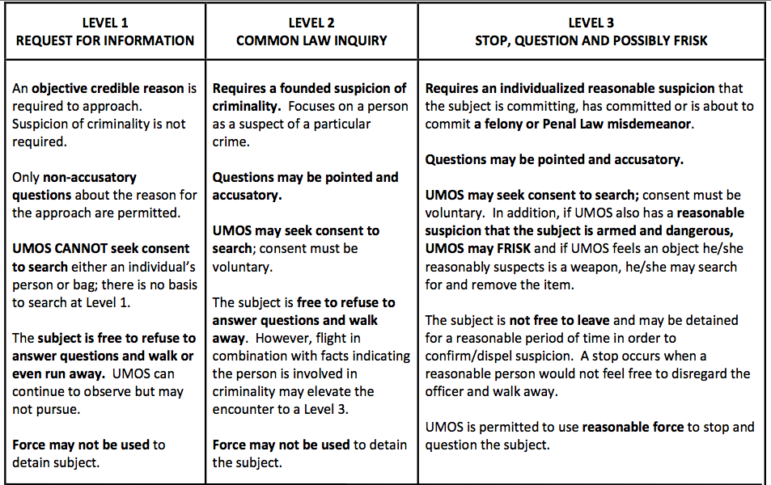

If a police officer walks up to someone only to ask questions like “Where are you going?” or “What are you doing here?” this is generally considered a “Level 1” or “Level 2” encounter—not an official “stop,” according to the NYPD’s patrol guide. In theory, a person can refuse to answer questions or leave the interaction at any point.

A Level 3, or “Terry,” stop—a “stop and frisk” stop—only occurs when an officer has “an individualized reasonable suspicion that the person stopped has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a felony or Penal Law misdemeanor,” according to the patrol guide. In this case, the civilian could not disregard the officer or walk away. A Level 4 stop involves an actual arrest. These Level 3 stops—and any Level 4 arrest that results from it—are the only kind that are included in stop-and-frisk statistics.

However, these are tricky lines to draw in practice. Experts have expressed concerns that many people would not feel free to walk away from a police officer under any circumstances. Encounters an officer might consider relatively benign might be having a profound impact—and be blurring the lines of the law.

“Officers are likely doing what they are trying to argue is less intrusive investigation, the

Level 1 and 2, and really people are experiencing it as a restraint on their freedom, which makes it legally a stop,” said Borchetta.

“Because black people in New York have experienced so much over-policing, many for their entire lives, they are not going to assume that they’re free to leave unless an officer tells them that,” she said.

Agostini agrees. These kind of encounters are “the everyday experience of black and brown young people in New York City,” he said. “We know that’s not going on in other parts of the city that are either whiter or more affluent.”

NYPD

A chart from an NYPD guidance document breaks down the different levels of police-civilian interaction.

Would you walk away?

Dister said that in his experience, he did not feel free to leave. “You never feel free to leave when you have someone asking you questions with a badge and a gun,” he said.

Charney reviewed a summarized version of Dister’s account. “The NYPD would probably say this is a Level 1 because, in their view, the questions the officers asked were not ‘accusatory,'” he wrote in an email. “I think asking somebody where they’re going and/or coming from is accusatory. I think this is at least a Level 2.”

However, if the situation was such that a “reasonable person,” in the courts’ parlance, didn’t feel free to leave, that could escalate the encounter to a Level 3, and therefore it would be considered a stop that should appear in NYPD stats, Charney added.

It’s precisely these ambiguities surrounding such experiences that worry so many experts, their concern bolstered by a spate of interviews and forums over the last several years.

Thousands of residents from the most heavily-policed areas of city participated in a series of community forums and focus groups over the last several years as part of the reform process. Participants frequently said they would feel uncomfortable walking away from an officer who was questioning them.

“I think I would need verbal confirmation [that I was free to leave] because people get shot out here by cops,” said one participant, whose identity was kept anonymous in records of the meetings.

The NYPD’s press office did not directly respond to request for comment, but did provide a link to its publicly available patrol guide, which can be found here.

A separate guide for officers on investigative encounters from 2016 provides the following comment: “Some individuals may feel as if their personal liberty is intruded upon and they are not free to leave whenever they have any interaction with a police officer. This should not be the case.”

The debate over ‘Right to Know’

The Right to Know Act, passed last December, was a recent legislative effort to bring more clarity to police encounters. One part of the act requires officers to ask for consent before searching a suspect and to explicitly explain that they have a right to refuse, in cases where there is no reasonable reason to do that search. A second part requires officers to identify themselves formally during encounters with civilians and to provide a business card if no arrest or summons occurs.

“The more that police are required to tell people what their rights are in an encounter, the more people will be able to exercise the freedom that the law intends them to have,” said Borchetta.

However, officers don’t have to formally identify themselves or provide business cards during low-level encounters. Although the act originally proposed it be required in low-level scenarios, in the end it was only applied to Level 3 stops.

At the time, this change was criticized by city council member Donovan Richards: “Let’s be clear. The most common interaction between police and my constituents are Level 1 and traffic stops, whether the data shows it or not,” he told City Limits in December.

Agostini sees this as an issue, explaining that the youths he works with, who are frequently approached by police officers, are typically not handed a contact card after such encounters.

“When my young people are in the park and they’re being asked to move or they’re being asked to leave, or they’re being asked for identification, they’re not receiving any documentation that this is an actual stop by a police officer, even though that we know that there is no reasonable suspicion for the police officers to be engaging with those young people,” he said.

A new request for change

Nobody knows how many low-level stops are taking place, although an ongoing study at NYCLU is trying to quantify this based on surveys.

To address these concerns, the facilitator of the Joint Remedial Process, the part of the court order that requires community input on the NYPD’s reforms, has submitted a request to the courts that officers keep some record of lower-level stops.

The NYPD initially rejected most of the recommendations that arose from the Joint Remedial Process, arguing that most of the suggestions were already underway. Documenting Level 1 and Level 2 stops, it argued, would create undue paperwork and a “chilling effect” on informal conversations. The NYPD has not yet responded to the plaintiffs’ counterarguments in its filing on Friday.

On top of not reporting low-level stops, official reports show a chronic tendency of officers to not report the Level 3 stops that they are required to document. A December report from the court-appointed monitor who is overseeing the reforms put underreporting of those stops as high as 42 percent for early 2017.

Despite this, most believe that the NYPD has indeed made some improvements to stop-and-frisk. Most observers believe that some of the decrease in stops has been real, and that fewer citizens are being stopped unnecessarily or without reasonable suspicion.

Moreover, the advent of community policing has been heralded as a way to improve the relationship between the police and the community.

“Neighborhood Policing reflects a cultural change for our entire agency…and for everyone who lives in, works in, and enjoys New York City,” Police Commissioner James P. O’Neill said in a May statement.

Eric Adams, Brooklyn’s borough president and a former NYPD captain who testified against the NYPD’s practices in the 2013 trial, said he rarely hears complaints about stop and frisk from his constituents now.

However, he believes that change takes time. “I think that anytime you attempt to reverse a long-standing condition, such as a culture, a police culture, it doesn’t change instantly. It’s like trying to turn around an ocean liner,” he said.

For his part, Dister doesn’t have high hopes that further legislation will change policing in his neighborhood. “They do as they please and there’s nothing we can do about it,” he said. “This is a very, very deep-rooted issue.”

This story was reported with the support of a grant from CUNY Graduate School of Journalism’s Urban Reporting Program.

10 thoughts on “‘Stop and Frisk’ is Over, But Low-Level NYPD Encounters Now Raise Concerns”

Pingback: Queens Today – QUEENS DAILY EAGLE

Two points:

There seems to be a conflict between the concept of community policing

(i.e. more frequent interactions between police and the community in order to to improve relationships and lessen hostilities & mistrust on both sides) and the concept of lessening and/or cataloguing “low-level” encounters. Where is the boundary, or is it all essentially the same in terms of police work?

As for people who are stopped in low level one encounters, those who are concerned about there safety and whether they are free to leave, the officer should proceed as follows:

Level one encounter:

Hi, I’m police officer X .

I don’t suspect you of breaking the law and you’re free to move on and not talk to me,

but I’d like to ask you (non-accusatory questions).

As opposed to level two encounters:

Hi: I’m police officer X.

You’re free to move on and you can refuse to be searched or answer questions,

but there has been (specific crime) in the neighborhood and you resemble the suspect

(or I have reason that you might be involved),

so I need to ask you (“pointed or accusatory” questions).

Of course it’s a bit wordy, but for level one interactions this would lesson fear and anxiety for the person stopped, and lessen the chance of the encounter unnecessarily escalating.

Pingback: After Repeatedly Failing To Document Stops/Frisks, NYPD Ordered To Record All Encounters – Miller Trades

Pingback: Museum of Broken Windows: artists on the dangers of racial profiling | Art and design | Top 10

Pingback: Museum of Broken Windows: artists on the dangers of racial profiling | Art and design | ap news,breaking news,us news ,current news,daily news

Pingback: Museum of Broken Windows: artists on the dangers of racial profiling | Transcultural Knowledges

Pingback: MTA Backtracks ‘Bus and Frisk’ Plan After Advocates Condemn ‘Cops on Buses’ Plan – Streetsblog New York City

Pingback: MTA Backtracks on ‘Bus and Frisk’ Plan After Advocates Condemn ‘Cops on Buses’ Plan – Streetsblog New York City ⋆ New York city blog

Pingback: Some More Updates/Info | BMCC ENG101-1500: Summer 2019 with Prof. Jaime Weida, 3:00 - 5:10 in F308

Pingback: Updates | BMCC ENG101-1800: Summer 2019 with Prof. Jaime Weida, 6:00 - 8:10 in F308