City Limits reformatting of CCC chart

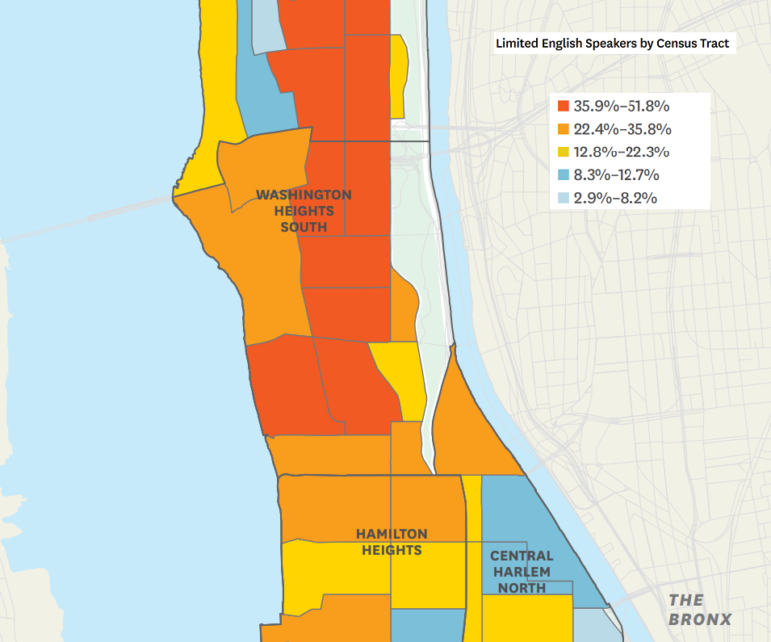

English proficiency is very uneven in the area.

In northern Manhattan, median income is rising, the poverty rate is falling, and rates of employment are going up.

That sounds like good news – and it is. But it’s not the full story.

The median income for Whites in Central Harlem is triple that of Latinos, a gap even wider than the 2:1 ratio that prevails citywide. Black households in Central Harlem, West Harlem and Washington Heights earn significantly less than Black householders elsewhere in the city.

The poverty rate in all three areas remains higher than the citywide rate, and for Black residents it is a stunning 30 percent, much higher than the 21 percent citywide rate for Black households.

Meanwhile, the benefit of those high employment numbers is tempered by the fact that, “Workers in Washington Heights, in particular, tend to be over-represented in the low paying fields of retail and hospitality (accommodation and food services) and under-represented in higher paying jobs such as those in finance and real-estate.”

That’s according to a new report by the Citizens Committee for Children that combines a deep dive into neighborhood data with a series of interviews with social-service providers and residents to try to figure out what’s going on in Northern Manhattan.

The area is of interest because, along with the South Bronx and Central Brooklyn, it’s long ranked high on CCC’s annual assessment of community risk factors. It’s also gentrifying steadily, and is bracketed by one completed rezoning by the de Blasio administration (in East Harlem) and another that will soon be voted on (Inwood).

According to CCC, a broad array of social risks confront the neighborhoods, and education is an area of particular alarm. In West Harlem and Washington Heights, 40 percent of Latinos lack high-school diplomas, compared with 33 percent citywide. School test scores are well below citywide averages, and the gap between early-childhood education enrollment among high- and low-income households is wider than in the city as a whole. Central Harlem has high numbers of young adults out of school and out of work. Central Harlem also displays a high and rising rate of homeless-shelter entry and among the city’s poorest health outcomes.

To be sure, there is some uncomplicated good news in the area. The rate of teen births has plummeted and the number of youth arrests is down, while the rate of health insurance coverage has increased faster than for the city as a whole.

But Jennifer March, the executive director the CCC, says she was struck in the qualitative research by, “the profound level of stress that people are under.” And that stress could reflect the dramatic ways the neighborhoods are changing. CCC researchers found a widespread sense that gentrification was changing the heart of each neighborhood, and a general anxiety about getting priced out.

Data backs up the perception of change: The White population in northern Manhattan has increased dramatically, and the Whites coming in tend to be wealthier than other Whites citywide. “You actually see greater disparities in income in these northern Manhattan neighborhoods when you compare them to the city as a whole,” says Apurva Mehrotra, director of research and data analysis at CCC and an author of the report.

Those disparities create a danger for demographic analysis, he notes: “There’s a risk of sort of seeing that some geographic areas are doing well and potentially losing sight of what’s really going on in that community.” That’s why the qualitative interviews with community members are important. “We know not everyone is experiencing these improvements in the same way,” Mehrotra says. “When we tell them, ‘Hey it looks like the poverty rate in Central Harlem is going down,’ they’ll look at you like you’re crazy.”

The interviews also helped tease out the investments local residents think would make a difference. A consistent theme, says March, was that the way in which assistance is offered might be just as important as the help itself.

“Folks we spoke to were really explicit about wanting to seek services in order to be more secure and economically mobile,” March says. People want classes in English, on entrepreneurship, on financial literacy. But for those offerings to be of any real value, they need to be paired with childcare. “Because they are so cash strapped, things need to be convenient. They have this dual responsibility of wanting to improve their education and career trajectory but also needing to do so in a manner that they’re children can safely cared for, and there’s not a lot of options where you can do both affordably and conveniently.”

The same goes for the programs the city has started to better protect tenants, like right to counsel in housing court (which is being rolled out incrementally across the city). Help is often available, but because of language barriers, the people most in need do not know about them.

“I do think the report reveals a need to think more strategically about how we’re communicating with populations that could avail themselves of the resources that exist in a way that makes it easier for very overtaxed people to understand what’s available for them,” March says.

One thought on “Study Reveals Stark Income Disparities and Widespread Stress in Northern Manhattan”

Pingback: Research Reveals Stark Revenue Disparities and Widespread Stress in Northern Manhattan - Metropolis Limits - NYC Breaking News